Geoffrey Graybeal and Amy Sindik

This study focuses on the civic engagement of high school journalism students in the so-called Millennial generation. Through a pilot study and focus groups, this paper examines the way high school journalism students feel about civic engagement, and if the students connect civic engagement to their works as young journalists. The focus group findings indicate that being involved in journalism does increase an interest in the community around them, and creates a group of students that believe they know more about current affairs than their peers. Cyclically, the students believe that civic engagement also helps develop their journalism skills.

Key Words: Civic engagement; scholastic journalism; Millennials; journalism students; community journalism; high school

Scholastic journalism students are caught in a civic quandary. As news consumption and press involvement often are cited as key aspects of civic involvement in their communities, young journalists find themselves simultaneously contributing to and being shaped by civic participation at a time when civic engagement continues a downward spiral among their generational cohorts (Delli Carpini, 2000; Mindich, 2005; Pew, 2010; Putnam, 2000; Reese & Cohen, 2000). Scholars, pundits, demographers, and analysts have attributed the decline in civic engagement to a generational gap (Delli Carpini, 2000; Mindich, 2005; Pew, 2010; Putnam, 2000; Schudson, 1998; Skocpol, 2003; Zukin, Keeter, Andolina, Jenkins & Delli Carpini, 2006).

However, other scholars argue the daily technology usage of the generation that contemporary scholastic journalists belong to equates to a shift in civic engagement, and not a waning, as a result of these technological changes (Gil de Zúñiga, Eulalia & Rojas, 2009; Gil de Zúñiga & Valenzuela, 2010; Zukin et al, 2006). Even Robert Putnam, whose Bowling Alone chronicles the decline of civic involvement and speculates on how this is harming the very fabric of American democracy (Putnam, 2000), appears willing to accept this premise (Sander & Putnam, 2010). Scholars, such as Delli Carpini (2000), envision the online realm as a space for political re-engagement, particularly for young people.

If this perspective is indeed the case, then the most recent generation of young journalists has much insight to offer, given they were born in, and have come of age in a disruptive technological time that has had transformative political, cultural, and social ramifications. Thus, this study examines the civic engagement of journalism students in the so-called Millennial generation, often identified as those born 1980 and after (Pew, 2010), and the way engaging in their communities impacts their journalism skills. These Millennial-generation journalism students are teenagers with what Community Journalism: Relentlessly Local author Jock Lauterer describes as a “sense of community” (Lauterer, 2006, p. 88). They have distinct communities (i.e. high school identities) both within their demographic (youth) and within their community (hometown).

The existing literature reveals three consistent patterns. The first is that civic engagement is a generational issue. The second is that civic engagement is changing. The third is that the defining characteristic of the Millennial generation, technology, is contributing to, and accelerating the changes in civic engagement, as well as participatory democracy. These shifts appear to be noticeable particularly with journalism students. Journalism classes have been found to increase civic knowledge in high school students (Clark & Monserrate, 2011). McLeod has advanced the idea of actively engaged adolescents participating in civic development through interactions with family, peers, teachers, and the media in contrast to young students as passive recipients of information from parents and teachers (2000). Community involvement and civic engagement occurs from skills developed from participation in school and in community volunteer activities and with news media use (McLeod, 2000) — the type of knowledge high school journalists gains vis-à-vis scholastic journalism programs.

The purpose of this study is to examine the civic engagement levels of high school journalism students, and the way civic engagement impacts journalism practices. Through a pilot study and focus groups, this paper examines the way high school journalism students feel about civic engagement, and if the students find a connection between civic engagement and their work as young journalists.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Youth, Community, and Civic engagement

Millennial generation scholastic journalism students are teenagers who identify not only with their high school communities, but with their hometown communities as well as within their own age group— which fill characteristics of community journalism offered by Lauterer (2006). While the Internet has expanded community beyond the geographic boundaries of audience members in a newspaper circulation area (Gilligan, 2011), another common definition of community journalism comes from the National Newspaper Association. The NNA, the leading trade group for nondaily and alternative newspapers, defines the term as a community and the newspaper joined by a “shared sense of belonging,” which can be “geographic, political, social or religious” and can exist in the “real” world or in cyberspace (Terry, 2011).Community newspapers, in particular, have long had ties to promoting civic engagement in their communities. A 2007 study by Jeffres, Lee, Neuendorf, and Atkin found newspaper reading supports community involvement, as newspapers “have been more active practitioners of civic journalism and its commitment to a more robust civic democracy” (p. 7).

More recently, two studies found further evidence of connections between local newspapers and civic engagement. In a 2011 study, “How people learn about their local community,” funded by the Pew Research Center’s Project for Excellence in Journalism, the Pew Research Center’s Internet & American Life Project, and the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, newspapers and newspaper websites ranked first or tied for first as the source people said they rely on the most for the most civically-oriented topics such as zoning, development, community events, local government and information about taxes.(Rosenstiel, Mitchell, Purcell & Rainie, 2011). In the other study, Yamamoto (2011) found evidence that community newspaper use promotes social cohesion, indicating community newspapers are important to community engagement. Yamamoto discovered that community newspapers provide “mobilizing information,” which facilitates participation in local community organizations and volunteer efforts. Taken together, these findings suggest that those who closely follow civic matters, while perhaps smaller in numbers, are more likely to be engaged in these matters. While using community news as a source for information does not necessarily directly equate with civic engagement per se, there is evidence that consumption may influence action.

Like community newspapers, broader definitions of community journalism also have long encapsulated civic values. In a study of mass communication scholarship over an 11-year period looking at the relationship between community and news media, Lowrey, Bozana, and Mackay (2008) found evidence that many of the explicit definitions of community journalism reflect civic or public journalism principles. Many of the articles took a normative tone assuming civic journalism principles benefit communities (Lowrey, Bozana, & Mackay, 2008).

News Consumption

Traditionally, newspaper consumption has been used as a surrogate measure of civic involvement. However, as traditional newspaper readership declines concerns abound regarding what the decline means for the state of democracy (Mindich, 2005; Schudson, 1998). Just as the decline in civic engagement has been cited as a generational problem, so has the continued decline in news consumption. Young people are estranged from the daily newspaper, have consumed much less news, and have failed to make news consumption a routine part of their day (Mindich, 2005). Reading newspapers ranked lowest among teens out of all available media options (Pardun& Scott, 2004). While newspaper readership is down across all demographics, newspaper readership among teenagers has decreased to an even greater degree. Teenagers who do not read the newspaper attribute this lack of use to the many media outlets competing for their time (Cobb-Walgren, 1990).

The Millennial generation is the first generation to be born with the Internet and brought up in a computer mediated environment (the creation of alternate realities through computer interfaces) (La Ferle, Edwards & Lee, 2000; Zukin, et al., 2006). The Millennial generation is a multitasking generation spending their entire lives connected to digital technology (Pew, 2010). These generational distinctions are shown in their news consumption habits. The Millennial generation relies heavily on television and the Internet for news, with 65% of Pew survey respondents indicating they received most of their news from television and 59% indicating they received most of their news from the Internet. Gen Xers (ages 30 to 45) and Millennials rely on Internet and television sources nearly equally, although television is still the leading news source for both of these younger cohorts (Pew, 2010). As a news source, Millennials (characterized in the Pew report as those born after 1980) are just as likely to use cable or broadcast television. They are less likely than Boomers (ages 46 to 64) or Silents (ages 65 and older) to get most of their national and international news from the major networks (ABC, CBS and NBC). Only 24% of Millennials surveyed receive most of their news from newspapers, and 18% use radio as their main news source (Pew, 2010).

Mindich (2005) worried the decline in news consumption among young people may lead to a decline in public affairs knowledge and democratic participation. However, studies have found parents and schools can encourage an increased use of newspaper and television (for news consumption) (Vraga, Borah, Wang & Shah, 2009) and civic engagement, particularly among tweens and teens (Golieb, Kyoung & Gabay, 2009) as well as scholastic journalism students (Graybeal, Dennis & Sindik, 2010).

Civic Engagement Habits

Pointing to the changing nature of civic involvement (which historically was tied to political engagement), Zukin et al. contrast civic engagement from political engagement by defining civic engagement as organized voluntary activity focused on problem solving and helping others (2006). The definition of civic engagement appears to be shifting, with no answer that fully encompasses civic engagement in the 21st century (Zukin et al., 2006). Determining a definition for civic engagement is difficult due to competing theories of democracy and empirical measures of participation (Zukin et al, 2006). Despite difficulties surrounding the meaning of the term, Delli Carpini defines civic engagement as the way individual and collective actions are designed to identify and to address issues of public concern. Civic engagement can take many forms, from volunteerism and organizational involvement to electoral participation (Delli Carpini, 2000; Delli Carpini, 2006; American Psychological Association, 2012). On the American Psychological Association website, the organization posits civic engagement can include addressing an issue directly, working with others in a community to solve a problem, or interacting with the institutions of representative democracy. Civic engagement encompasses a range of specific activities such as working in a soup kitchen, serving on a neighborhood association, writing a letter to an elected official, or voting in elections (American Psychological Association, 2012).

Scholars often have tied civic engagement to news consumption in that when news consumption decreases, so does civic engagement. And although one perspective considers the Millennial generation’s decrease in civic engagement as inevitable as news consumption decreases, not all predictions for future news consumption and civic engagement decline are dire (Schudson, 1998; Skocpol, 2003; Zukin et al., 2006). Scholars argue that forms and types of civic engagement and news consumption have changed; therefore, researchers should make a similar effort in finding the appropriate methodological ways to measure the new cultural and media landscapes. Parents (talking about politics at home) and schools (arranging for volunteer opportunities) are the most powerful predictors of engagement, among high school and college students (Zukin et al, 2006). Opportunities in high school to learn about civic engagement can be related to the ability to engage in civic activities (Kahne & Middaugh, 2008). Empirically, recent studies have shown that Millennials often volunteer at higher rates than Americans in other generations, suggesting an interest in civic engagement still exists (Civic Health Index, 2009; Pew, 2010).

Besides volunteering more than other generations, Millennials are on par with other generations in the frequency with which they sign petitions online and paper petitions (Pew, 2010). About one-third of Millennials, Gen Xers and Boomers say they have boycotted a company in the past year. And nearly as many said they have participated in “buycotting” in the past year, which is purchasing a product or service to show support for a company whose business practices one believes are ethical (Pew, 2010). Millennials often use their favored news resources and new technologies to share information regarding civic engagement (Civic Health Index, 2009). Millennials are more likely than older generations to use the Internet, blogs, text messaging and social networking sites to gather civic-related information and express their opinions on issues (NCOC, 2009).

Some best practices for civic engagement in the high school classroom include the discussion of current events, the study of issues important to students, the discussion of social and political topics in an open classroom environment, the study of government, history and social sciences, the interaction with civic role models, the participation in after-school activities, the study of community problems and ways to respond, the service learning projects, and the engagement in civic engagement simulations (Kahne & Middaugh, 2008).There is strong evidence that talking about politics and civic participation today leads to civic participation and to political participation in the future (Gil de Zúñiga & Rojas, 2009).

Technology and Civic Engagement

Scholars have conducted research into effects of technology on civic engagement in both online social networks (such as blogs and social networking sites like a Facebook) and offline social networks (such as neighborhood and educational associations like a PTA). Network size, both online and offline, is related positively with civic engagement and online networks entail greater exposure to weak ties than offline networks (Gil de Zúñiga & Valenzuela, 2010). Some of the barriers preventing access to developing weak ties offline can be overcome by the geographically boundless Internet,. Also, engaging in conversations online has a stronger relationship with civic involvement (Gil de Zúñiga & Valenzuela, 2010). Other research has honed in on the types of Internet content that foster higher levels of civic engagement. News consumption, both online and offline, positively relates to interpersonal discussion, to political involvement and to political engagement (Gil de Zúñiga, Eulalia, & Rojas, 2009).

Mesch and Talmud (2010) found that Internet connectivity and attitudes toward technology provide more channels for local civic participation. Formation and active participation in local community electronic networks not only adds to, but also amplifies civic participation and an elevated sense of community attachment (Mesch & Talmud, 2010). Overall, active participation in locally based electronic forums is associated with multiple measures of community participation over other traditional (offline) forms of social capital, such as face-to-face neighborhood meetings, talking with friends, and membership in local organizations (Mesch & Talmud, 2010).

In summary, a generational gap has led to declines in both news consumption and civic engagement. A news habit has not developed among members of the Millennial generation, the first to be surrounded by digital technologies at birth. When news consumption decreases, so does civic engagement, however, participation in school activities can stimulate an interest in civic engagement. This study looks how participating in high school journalism studies impacts civic engagement. Thus, the following research questions are posited:

RQ1: How does participating in high school journalism impact civic engagement?

RQ2: How does students’ focus on online news impact civic engagement?

METHODS

This study used mixed methodology of a pilot survey and focus groups to determine the dependent variable of civic engagement. Using Delli Carpini’s characterization of civic engagement as a guiding point, this study operationalized civic engagement as involvement in community, involvement in civic and/or political events, as well as an awareness of issues impacting the respondent’s community. The independent variables were high school journalism practices and online engagement. High school journalism practices were operationalized as high school students who engage in journalism activities for their high school. Online engagement is operationalized as level of online use. The participants were high school students attending a week-long summer scholastic journalism academy at a university in the southeastern United States in 2009 and 2010 (n= 147). The journalism academy consisted of high school students — mostly from the host state — that enrolled in one of four writing courses or one of three visual communication courses. At the end of the week, students produced a 12-page newspaper and a 15-minute broadcast TV news show. To attend the journalism academy, students must either pay for the $525 tuition or apply for a scholarship. Roughly 25% of the participants attended on scholarships funded by CNN or the Hispanic Scholarship Fund. Although open to all students who demonstrate financial need, the scholarships are marketed to students in schools with high concentrations of African American and/or Latino students.

Pilot Study

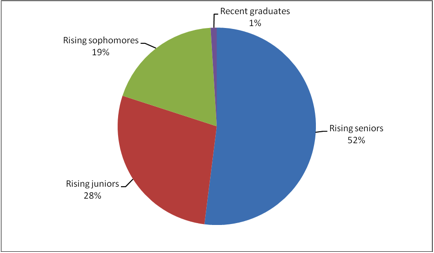

A pilot survey of students was conducted at the journalism academy to gain initial impressions regarding the participants’ general news and media consumption habits to determine ideal focus group participants. The survey measured media consumption habits, attitudes toward community engagement, civic involvement, and interest in news and current events. The optional online survey was conducted during academy classes and had a 97% response rate (n = 142). The convenience sample was comprised of 84% female respondents and 16% male. Statewide and national demographic data of scholastic journalists was not available so it is unknown if the survey sample is representative of a typical make-up of scholastic journalism participants or heavily skewed toward female respondents. A national study of recent college journalism programs, however, found 75% of recent graduates were female, which seems to suggest the skew toward females is normal among journalism students (Becker, Vlad, Olin, Hanisak & Wilcox, 2009). The majority of the survey respondents were upperclassmen (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Grade level of respondents

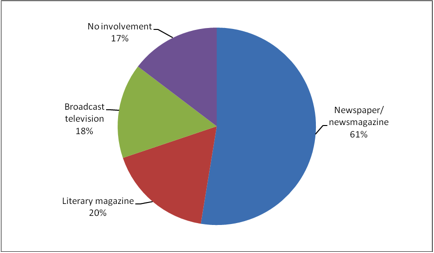

Many of the respondents are involved in multiple media outlets in their high school, with the newspaper or newsmagazine being the most popular outlet (Figure 2). While most of the respondents had experience in scholastic journalism, nearly one-fifth of survey respondents are not involved in a media outlet at their high school, 17%, n = 24. This suggests summer scholastic journalism academies fill a void for students interested in journalism who might not be involved in media outlets in their own high schools.

Figure 2: Scholastic journalism activity

The majority of respondents are Caucasian, 60%, n = 82. Because a focus of the journalism academy is exposing minorities to journalism opportunities, there are a greater number of minorities represented in the sample. This is more than double the number of college journalism graduates (19%) who are members of racial ethnic minorities (Becker et al., 2009). Survey respondents were allowed to check more than one option for their minority status. A majority of survey respondents (58%) identified themselves as members of racial minorities. Participants indicated several minority groups they identified with including African American, Asian, Latino, Native American, Indian and multiracial.

Focus Groups

The purpose of the focus groups was to determine the level of civic engagement felt by the high school journalism students (n = 32). The students participated in one of four hour-long focus groups conducted during the week-long academy. Focus group participants were grouped on different criteria selected by the researchers. One group consisted of rising sophomores; another group consisted of rising seniors; another group consisted of students with an interest in writing; and the fourth group consisted of students with multimedia interests. The focus groups further delved into many of the subjects covered in the survey. The focus group questions were pre-tested in an in-depth interview with a local high school journalism student. The focus group moderator routinely conducted member checks throughout the focus groups by summarizing and clarifying the statements being made and asking for agreement or corrections to his statements. The high school journalism academy director also presented a preliminary summary of research findings from the survey at the academy. This, in effect, also served as a de facto member check on validity to help show that the survey asked what the researchers intended to ask.

RESULTS

Pilot Survey

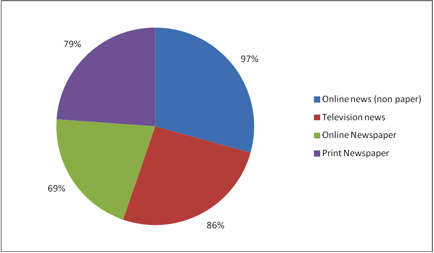

The high school journalism students were heavy consumers of media products, with newspapers, the Internet and television being the biggest sources of media consumed at least once a week (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Media consumption habits

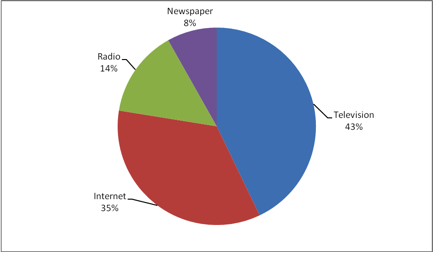

Forty percent of the participants read the news online every day (n = 53), but are not heavy consumers of mobile news, with 71% (n = 100) never checking the news on their phones or other new media products, such as podcasts. However, the phone and email are the main ways the respondents communicate with their friends (59%, n = 83), suggesting that the uses for mobile devices are primarily social for this group. In terms of news consumption, television is the primary source of news for the participants, followed by the Internet, radio and the newspaper (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Primary source of news

In addition to demonstrating high levels of media consumption, the survey respondents also had high levels of civic engagement, with 60% of the respondents stating they are somewhat involved in community, civic and political events, n = 58. An additional 9% (n = 13) described themselves as extremely involved and 16% (n = 23) described themselves as very involved in community, civic and political events. The remaining 14% (n = 20) described themselves as not at all involved in civic events. There was a moderate relationship between being involved in community, civic and political events, and having an interest in news and civic events, r = .310, p < .001. There was also a moderate relationship between respondents who were involved in civic events and respondents who get their news from the Internet at least once a week, r = .264, p < .01. A low correlation also existed between respondents involved in civic events and those interested in broadcast journalism, r = .187, p < .05.

Focus Groups

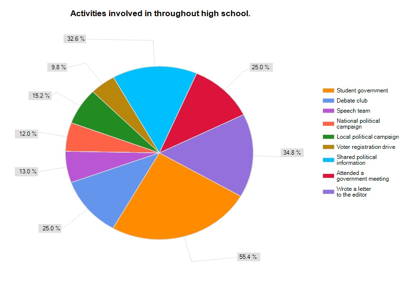

The study’s focus groups provided more in-depth information into what the high school journalism students think about civic engagement. The importance of civic involvement was prevalent across all four focus groups, with many of the participants being involved in their own communities through volunteer work (civic service programs, elementary schools, church work and Habitat for Humanity) and active in civic engagement activities through their high schools (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Civic engagement activities in high school

High School Journalism

In response to the first research question, the focus group participants stated that being involved in a high school journalism program provided them with more opportunities for, and a better appreciation of, civic engagement activities. The participants explained civic engagement increased their understanding of what was happening in their communities, which in turn made them better journalists. The participants also believed high school journalists, as well as their non-journalism peers, should be engaged actively in civic activities as early as possible, and definitely should be engaged by the age of fourteen or fifteen. One focus group participant who volunteered at an elementary school explained:

We worked with the kids and really find out where the news is. You can really write a story better when you know how the news feels firsthand [rather] then just going out there and interviewing somebody. We were actually experiencing it. Some of my best news stories have been done after doing community service.

Another participant echoed these sentiments when explaining the ways her high school newspaper attempted to integrate itself into the community to produce in-depth stories, and attempted to advocate the merits of civic journalism. She believed “most of your best stories are from going to the homeless shelter, going to a food drive – don’t look down on the community and think you know about everything if you aren’t being affected.” These statements suggest civic involvement can enhance journalism skills and can impact the type of news stories written by journalists who are active in their community. It also suggests when at the grassroots level, civic engagement and scholastic journalism influence and inspire one another.

The focus group participants also felt being civically engaged in their communities allowed them to discover stories they would not learn about from the news they consumed online, or from other media sources. One participant stated, “I feel like [civic activities] can get you closer to the news. I feel like instead of doing stories about how bad the economy is, if you go and see it firsthand that will give you a better understanding of it instead of going and looking it up on the Internet.” In addition to this perspective, some of the focus group participants also felt that civic engagement involved their interest in journalism and local media. A participant who attended a school for the blind expressed the belief that being involved in civic affairs made her more interested in the media:

I think it is important for people to be involved. At my school we are from all over the state so we try to be as involved in the community as we can. It’s important to give back to the community. As blind people, we show what we are capable of in the community and it makes you pay more attention to the local news. You hear about it firsthand.

However, not all of the focus group participants believed the civic engagement was necessary for a career in journalism, and also reflected pessimism when describing the civic interests of their non-journalism school friends and classmates. One participant stated, “I think that kids are turning more towards apathy in terms of being involved,” and believed that unless his peers had specific civic goals or future career plans in mind, they likely would not be motivated to engage in civic activity.

The participants also shared the belief that the combination of civic engagement and journalism made them more aware of current events than their classmates, and expressed a certain unhappiness with the civic awareness level of their classmates, complaining their peers who were eligible to vote either did not know the issues well enough or chose not to vote at all. Some of the participants recognized a connection between their news and current events knowledge, and political and civic involvement. One female participant spoke passionately about the significance of an informed citizenry toward political and civic engagement:

I think it’s extremely important for people our age to know and understand the news because I just feel like there’s a lot of ignorance going on. There’s a lot of ignorant people, especially in our age group. They don’t know anything. You ask them and they’ll just be like (*blankly stares*). I don’t know. I just have a big thing against ignorance, I guess. I just feel like young people need to get more in touch with the news now, especially now with so many more things going on.

Overall, participation in high school journalism appears to positively impact the level of civic engagement for high school students, as well as an appreciation of the civic engagement activities. High school journalism students believed civic involvement increased the depth and quality of their stories, and explained civic involvement also increased their news consumption so they could be better informed as to what was happening in the world around them, particularly in their local communities. While the participants were aware that not all of their peers shared an interest in civic engagement, the participants clearly believed being actively engaged in volunteerism, politics and other civic activities had positive benefits for them, both as journalists and as humans.

Online News

In response to the second research question, the most popular ways for focus group participants to consume media was through new technologies and online media. The participants acknowledged the ease in blending media consumption with media creation enabled by new technologies had blurred the lines of professional and amateur content. The proliferation in use of social networking sites such as Facebook to gain information further complicates what the student journalists and their friends consider news. And while the aspiring student journalists recognized they would one day likely be creating content for online platforms, they said that professional online news sources needed to remain viable to maintain civic engagements for themselves and their peer groups. The students, many whom grew up in households where their parents regularly listened to and read legacy media outlets such and The New York Times and NPR, said traditional media outlets still do a better job of facilitating civic engagement than new technologies with content derived from less of a professional journalistic ethos.

The focus group participants watched a clip from “EPIC2014” video, which depicts the effects of an increasingly converged world may have on journalism and society at large in a hypothesized future that culminates with the downfall of The New York Times at the hands of a merged Amazon-Google technology giant. “EPIC2014” was produced in 2004 by Robin Sloan and Matt Thompson, who both worked at the Poynter Institute at the time, as an imagined future media history to depict the waning fortunes of the Fourth Estate. In the clip, The New York Times has gone offline, and the fictitious Googlezon company has replaced “news” with the Evolving Personalized Information Construct (EPIC) – a meta-tagged world of facts and notes and media assets mixed and re-mixed for every reader.

The participants were divided as to whether the future projected in the video could happen and threaten future civic engagement. One focus group participant believed the concepts shown in the video had happened, as more traditional media properties moved online. Another participant echoed this belief, explaining as more news is received online; people are not interested in getting different versions of the same story. The participant added “I don’t think people will all get news from different places because then no one would have the same story.”

A larger portion of focus group participants did not believe the future shown in the EPIC 2014 video would occur, for both civic and logistical reasons. One participant believed local news was too important to allow such a scenario to occur, adding, “Logistically [it] wouldn’t happen. All news is local. Unless you had people actually report on things, there would be no news.” Another student also dismissed the idea by considering the media employment side of the scenario, stating “I certainly don’t think as long as there’s kids interested in writing for The New York Times, I don’t think the pendulum will ever fully swing to the side of social media dominating.”

Other participants also believed the situation in the video would not occur, but believed the audience, not the media, would be the most resistant to the changes because one dominant media platform would not provide information everyone would want to read. If the audience were not interested in reading the content, they would just stay away from the new media source. As one participant explained, “You have to make it interesting enough for me to actually get into it. If what’s going on is not interesting enough I’m not going to read it.” Another participant echoed this concern, adding “It’s more about the people. [You] can’t make people read the paper. There’s people who just will never read the newspaper and you can’t really change that. There’s a lot of people like that.”

Overall, the focus group participants did not believe the shift to online journalism that is currently occurring would lead to a world in which civic engagement was no longer practiced. Like research has predicted (Zukin et al., 2006), the participants mainly believed an increasingly online world would not erase civic engagement, but would rather shift the terms and practices in some manner. The participants believed due to both the ideals and motivations of journalists and readers, the bleak world of an online future with one dominant voice would not come to be. Journalist and audience interest would ensure civic engagement would continue. Considering both the journalist and audience angles of future civic engagement indicates the participants believe that both parties are responsible for maintaining and increasing civic activities and awareness.

CONCLUSION

This study indicates when it comes to civic engagement, participation in high school journalism matters. The focus group participants credited their experiences with scholastic journalism programs for not only fostering an interest in news and current events, but also for fueling a desire to be engaged in local and national civic and community matters. The high school journalism participants expressed a strong advocacy of civic engagement, and expressed a connection between civic engagement and journalism skills. Nearly uniformly, the focus group participants felt being civically engaged enhanced their journalism skills and made them more aware of their surroundings, which in turn gave them inspiration for ways to cover their local communities. The sentiments of the focus group participants indicate civic engagement is not dead, but may be shifting as the Millennial generation consumes news in different fashions. While the participants expressed a preference for online news, they did not believe this preference would drastically change the role civic engagement had on their journalistic habits and story preferences.

Just as Graybeal, Dennis & Sindik (2010) found parents and teachers to be powerful influencers on teenagers’ interest in news; this study finds those two key groups to have an influence on teenagers’ civic engagement. The study also echoes previous findings that parents and schools are the most powerful predictors of engagement (Golieb, Kyoung & Gabay, 2009; Lee & Wei, 2007; Vraga et al., 2009; Zukin et al., 2006). Theoretically, this paper offers a contribution to the shifting notion of civic engagement. Like Zukin et al., Gil de Zúñiga, Schudson, Skocpol and even Putnam himself, this study found evidence civic engagement is changing, not necessarily declining, at least among the scholastic journalists belonging to America’s first generation to grow up with the advent of the Internet. Given that Putnam has said the stakes in stopping the decline of civic engagement is the fate of American democracy itself, this appears to be good news for America.

Of course, the extent of the impact on civic engagement of the Millennial generation’s increasing focus on online news is less clear. While acknowledging a high use of online technologies among both themselves and their peers, the focus group participants expressed a greater trust in traditional media as credible sources of information. Their own political and civic engagement and knowledge also was spurred more from traditional media and participation in scholastic journalism programs than the emerging technologies. The high school journalists believe strongly in the future of the industries they hope to one day work in, and bemoan the doom and gloom scenarios of the fall of mainstream news outlets and the resulting ramifications for democracy.

Despite the promising results, there are a number of limitations with this study. The first is the study was limited to a non-random sample of high school journalism students. The survey and focus groups were a convenience sample of all the journalism academy participants. As a non-random sample of high school journalism students, the results of this study are not generalizable to either the total population of high school journalism students, or the total population of Millennials. The students participating in the high school journalism academy are sophisticated media users, whose views on media use and civic engagement may not be representative of all teenagers. However, as an exploratory study beginning to examine the civic engagement patterns of high school journalists, the study adds value to the literature on the civic engagement of young journalism students.

Nevertheless, the study offers some initial insights and grounds for future research. Little previous research has examined teenagers’ civic engagement, much less the civic engagement of scholastic journalists. This study offers hope that scholastic journalism programs are useful tools to facilitate civic engagement. Future research is needed to further examine the civic engagement feelings and patterns of high school journalism students. Future research could include a longitudinal study tracking the civic engagement activities and feelings of high school students at future journalism academies. Additional research also could investigate the civic engagement sentiments of all high school students’ civic engagement as well as a broader sample of Millennials, to examine if the civic engagement of high school journalists differs from the engagement of general high school students.

WORKS CITED

- American Psychological Association (2012). “Civic Engagement.” Retrieved June 13, 2011 at http://www.apa.org/education/undergrad/civic-engagement.aspx

- Becker, L., Vlad, T., Olin, D., Hanisak, S. & Wilcox, D. (2009). 2008 annual survey of journalism & mass communication graduates. Journalism & Mass Communication Educator, 63 (3), 28-63.

- Civic Health Index 2009: Civic Health in Hard Times (2009). National Conference on Citizenship. Retrieved April 26, 2010 at http://www.ncoc.net/index.php?tray=content&tid=top47&cid=2gp54

- Clark, L. S., & Monserrate, R. M. (2011). High school journalists and the making of young citizens. Journalism, 12 (4), 417-432.

- Cobb-Walgren, C.J. (1990). Why teenagers do not read all about it. Journalism Quarterly, 67(2), 340-47.

- Delli Carpini, M.X. (2000). Gen.com: Youth, civic engagement, and the new information environment, Political Communication, 17 (4), 341-9.

- Delli Carpini, M.X. (2006). Michael X. Delli’s definition of key terms. Message posted to http://spotlight.macfound.org/blog/entry/michael-delli-carpinis-definiti…

- Gil de Zúñiga, H., Eulalia, P., & Rojas, H. (2009). Weblogs, traditional sources, online and political participation: An assessment of how the internet is changing the political environment.New Media & Society, 11(4), 554-574.

- Gil de Zúñiga, H., &Valenzuela, S. (2010). Effects of online and offline discussion networks and weak ties on civic engagement. Presented at the 11th annual International Symposium on Online Journalism, Austin, Texas.

- Gilligan, E. (2011). Online publication expands reach of community journalism. Newspaper Research Journal, 32(1), 63-70.

- Golieb, M. R., Kyoung, K. &Gabay, I. (2009). Political consumerism and youth citizenship: The development of identity politics among Tweens and Teens.Paper presented at the Association for Education in Journalism & Mass Communication annual conference, Boston.

- Graybeal, G.M., Dennis, J.G. &Sindik, A. (2010). Scholastic Millennials and the media: News consumption habits of young journalism students.Presented at the Association for Education in Journalism & Mass Communication annual conference, Denver.

- Jeffres, L.W., Lee, J.; Neundorf, K. &Atkin, D. (2007). Newspaper reading supports community involvement. Newspaper Research Journal, 28, 1, 6-23.

- Kahne, J.,& Middaugh, E. (2008). Democracy for some: The civic opportunity gap in high school. CIRCLE Working Paper 59.

- Lauterer, J. (2006). Community journalism: Relentlessly local, 3rd ed. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

- La Ferle, C., Edwards, S.M., & Lee, W.N. (2000). Teen’s use of traditional media and the Internet. Journal of Advertising Research, 40(3), 55-65

- Lee, T., & Wei, L. (2007). The impacts of declining newspaper readership on young Americans’ political knowledge and participation: A longitudinal analysis.Paper presented at the Association for Education in Journalism & Mass Communication annual conference, Washington D.C.

- Lowrey, W., Brozana, A. & Mackay, J.B. (2008). Toward a measure of community journalism. Mass Communication & Society, 11, 275-299.

- Mesch, G. & Talmud, I. (2010). Internet connectivity, community participation, and place attachment: A longitudinal study. American Behavioral Scientist, 53, 1083-1094.

- Mindich, D (2005). Tuned out: Why Americans under 40 don’t follow the news. New York: Oxford University Press USA.

- McLeod, J.M. (2000). Media and civic socialization of youth. Journal of Adolescent Health, 27 (2), 45-51.

- NCOC (2009). The emerging generation: Opportunities with the Millennials. National Conference on Citizenship. Retrieved April 26, 2010 at http://www.ncoc.net/index.php?tray=content&tid=top0&cid=2gp73

- Pew Research Center for the People & the Press (2010). Millennials: Confident-Connected-Open to Change

- Pardun, C.J., & Scott, G.W. (2004). Reading newspapers ranked lowest versus other media for early teens. Newspaper Research Journal, 25(3), 77-82.

- Putnam, R. (2000). Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- Reese, S., & Cohen, J. (2000). Educating for journalism: The professionalism of scholarship. Journalism Studies, 1 (2), 213-217.

- Rosenstiel, T., Mitchell, A., Purcell, K. & Rainie, L. (2011). How people learn about their local community. Pew Research Center Project for Excellence in Journalism, Pew Internet & American Life Project, Knight Foundation report. Retrieved September 26, 2011 from http://www.knightfoundation.org.

- Sander, T.H., & Putnam, R.D. (2010). Still bowling alone? The post 9-11 split. Journal of Democracy,21 (1), 9-16.

- Schudson, M. (1998).The good citizen: A history of American civic life. Washington D.C.: Free Press.

- Skocpol, T. (2003).Diminished democracy: From membership to management in American civic life. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press.

- Terry, T.C. (2011). Community journalism provides model for future. Newspaper Research Journal, 32 (1), 71-83.

- Vraga, E., Borah, P., Wang, M., & Shah, D. (2009). Building the habit: Growth in news use among teens during the 2008 campaign. Paper presented at the Association for Education in Journalism & Mass Communication conference, Boston.

- Yamamoto, M. (2011). Community newspaper use promotes social cohesion. Newspaper Research Journal, 32(1), 19-33.

- Zukin, C., Keeter, S., Andolina, M., Jenkins, K. and Delli Carpini, M.X. (2006). A new engagement? Political participation, civic life, and the changing American citizen. New York: Oxford University Press.

About the Authors:

Geoffrey Graybeal, Ph.D., is a visiting assistant professor in the School of Communication at the University of Hartford.

Amy Sindik, Ph.D., is a visiting assistant professor at the University of Georgia’s Grady College of Journalism & Mass Communication.

graybealsindik-cj1-2012