Candace R. Nelson, Bob Britten and Jessica Troilo

As women across West Virginia continue to ascend the editorial ranks of the state’s newspapers at an increasing rate, it’s valuable to study how they obtained their positions and what role culture – Appalachian, newsroom, and others – has played in the process. Ten women in high editorial positions at West Virginia newspapers were interviewed, and their experiences were analyzed using grounded theory. A sense of community was the unifying concept, and they identified insider/outsider barriers, community boosts and complications, and reciprocity as the main factors comprising it, with their sex playing a lesser but still notable role.

Newspapers in Appalachia, specifically West Virginia, tend to lag behind the national average in terms of advancement due to shortcomings in technology, manpower and resources (Partridge, Betz, & Lobao, 2012). In terms of employing women in editorial positions at those newspapers, however, West Virginia is on par with the rest of the country with about 30 percent of the total editors being women (American Society of Newspaper Editors, 2012). This often overlooked, understudied group of people can provide a glimpse into the world of Appalachia and a better understanding of its culture, specifically the women of West Virginia. Moreover, this research contributes to the understanding of community journalism as a whole. With the odds being against women rising in the newsroom ranks and a culture known for being humble and refraining from bragging about success, how do women who did, in fact, obtain a powerful position view their own career paths?

Roles are constantly changing within journalism, and women are making more progress, albeit slowly (Enda, 2002). Women are beginning to make more important decisions within the industry, and it has been shown that women present the same news judgment as men (Craft & Wanta, 2004). The media industry has been slow to accept women as leaders, yet women continue to make strides within journalism (Enda, 2002). This increase of women rising to the top of the news industry warrants attention from media professionals, as well as others, to examine how women view themselves, especially within rural areas.

This research will examine how Appalachian women view their careers in journalism in the context of culture. How do women, who reach a position that few women across the United States hold (American Society of Newspaper Editors, 2012), believe they reached that role? What, if anything, do they believe helped lead to that position in terms of outside factors? And what elements of Appalachian culture do they perceive as contributing to that line of thinking concerning career paths? All of these elements will help contribute to the overall understanding of women in media, specifically within West Virginia, and contribute to literature looking at the culture of West Virginia and community journalism overall. Because gender issues and regional culture play a vital role in community journalism, this research contributes to the understanding of rural journalists in community publications.

Women in Editorial Roles

Journalism in the United States has been dominated by men (Lewis, 2008), though the numbers are slowly changing. Most top editors at major newspapers are men (Reed, 2002); in 2012, slow progress has been made; 37 percent of all reporters and 34 percent of newsroom supervisors were women (American Society of Newspaper Editors, 2012). Major online news sources remain male-dominated, and women are missing from the most senior rank of editor-in-chief or executive editors (Creedon, 2007). Many newsrooms still exhibit patriarchal cultures, which alienate women (Elmore, 2007). Characteristics include low priority for “women’s” issues coverage, leaving women out of decision-making positions, and few accommodations for women with family responsibilities (Ross, 2001). In the past, nearly 40 percent of female journalists perceived sex-based discrimination in their own careers (Walsh-Childers & Chance, 1996). Women lead newsrooms in much the same ways as men and treat both male and female reporters similarly (Craft & Wanta, 2004), yet the proportion of female editors in newsrooms lags severely. The lack of significant change for women in media has become a roadblock (Armstrong, 2014).

The roots of this culture trace to the earliest days of women in journalism. Many male editors of the 1900s believed the woman’s place was in the home, often assigning them to domestic topics such as fashion and food (Lewis, 2008). They were often not allowed to cover crime beats because these were assumed to be too shocking or frightening (Goward, 2006), and women made up a minority of sports reporters. This trend persists to this day (Kian & Hardin, 2009).

When women are consistently put on low-priority beats, their chances for advancing to positions that require oversight of hard news is limited (Beasley & Gibbons, 1993). Studies of news content have showed that women are trivialized when compared to their male counterparts (Armstrong, 2014). Women tend to support family-friendly policies, openness, teamwork and communication (Everbach, 2006) in newsrooms. Women say they encourage participation and share power (Rosener, 1990). But the women in high-level positions tend to show the same type of leadership behavior as men, which some scholars argue shows journalistic values coincide with typically masculine ones (De Bruin, 2000). Thus women who take on traits such as being aggressive, coercive and tough tend to get ahead (Mills, 1988; Toegel & Barsoux, 2012). “It could be the case that only women who exhibit the same sorts of leadership styles and behaviors as male leaders make it through” (Riggio, 2010). The result is a culture that systematically prevents many women from advancing to top editorial positions.

While it has become more common to see women entering journalism, it remains infrequent to see them rise to the top. Published announcements of female reporter hires, for example, are rarely treated as notable, yet when a woman has become the editor-in-chief of a large market newspaper, her sex is often still treated as newsworthy (Enda, 2002). While women are increasingly common in city editor, news editor or section editor positions, men remain more common at the upper managerial level (Lee & Man, 2009).

News media, however, have been slow to report on their own profession’s gender gap, and as female journalists attempt to fit in, they have helped to perpetuate the trend (Goward, 2006). For example, some have felt the need to keep silent about any sexual harassment in the workplace rather than risk harm to how they are perceived in the male-dominated newsroom. Although the numbers of women reaching editorial positions has not made recent significant gains, however, some women do rise to those top roles (Enda, 2002). This study’s focus on such women in small rural publications is intended to investigate one smaller, less noticed, part of the current landscape.

Small-town Newspapers

Small, local newspapers tend to focus on local news, in contrast to their large counterparts, which tend to cover metro areas and national and international news. Many of the journalistic values famously identified by Herbert Gans (1980) are on clear display in the small-town press, especially ethnocentrism (emphasizing the values of the region) and small-town pastoralism – many newspapers in these areas place an emphasis on the average American (Garfrerick, 2010). When the United States newspaper industry began to suffer significant blows in the 21st century, due in significant part to online competition and to the recession, community newspapers fared better than the larger, city-based dailies (Cross, Bissett & Arrowsmith, 2011).

Research on newspapers in rural areas is sparse (Smith & Wiltse, 2005). Small media organizations without competition have, in the past, been successful in terms of circulation and profit (Downie & Schudson, 2009). In fact, about 70 percent of smaller daily newspapers continue to be more profitable than their larger cousins (Morton, 2009). Community-based, hyperlocal non-daily papers seem to be doing well in general because they are concerned with their civic responsibilities (Bradshaw, Foust, & Bernt, 2005). In West Virginia, there are currently 81 paid-circulation newspapers with a total market circulation of 656,815; 59 are non-daily newspapers, 12 of which have Sunday papers, and 22 are daily newspapers (West Virginia Press Association, 2012). Of these 81 newspapers, 28 (34%) have a woman in an upper editorial role.

With small staffs and few resources, editors at small papers typically do not have the opportunity to specialize in one particular area (Kirkpatrick, 2001). The community newspaper editor is hands-on in both journalistic practice and in administrative duties such as scheduling and payroll. Editors at community papers also must be involved with that community – attending bake sales, volunteering at baseball games and organizing food drives – engaging the local readers in person in order to best tell the stories no one else can cover (Bunch, 2008). Community newspapers are charged with providing information about local or regional events as well as social issues (Campbell, Smith & Siesmaa, 2011). Editors in these positions must be equipped to tell their audiences a range of stories under pressure because they are the only ones in the position to do so (Kirkpatrick, 2001).

Rural newspapers are characteristic of Appalachian culture. While research on Appalachian culture is limited (Tang, 2007), the region is generally understood be along the Appalachian Mountains, including the entire state of West Virginia and parts of Alabama, Georgia, Kentucky, Maryland, Mississippi, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Tennessee and Virginia. Appalachian culture varies by definition from person to person (Clark, 2013), but conditions such as a high poverty rate, the collapse of both steel and mining industries, and a cherished cultural heritage are typically cited as its hallmarks (Lohmann, 1990).

RESEARCH QUESTIONS

The research will examine how top-level female newspaper editors in West Virginia perceive the influence of Appalachian culture on their career. Do they consider Appalachian culture a contributing factor? Because it is less common for women to hold top editorial positions (Lee & Man, 2009), such women are of particular interest. How the participants describe their careers places their attitudes in perspective. It is also relevant to examine whether they view education, experience, regionalism, or other attributes as significant factors.

RQ1: How do top female editors at West Virginia newspapers describe their paths to their current positions?

In addition to being a female editor in a field where they are not prevalent, the participants are also performing the job in a particular location: West Virginia. Some may see editing a newspaper in West Virginia as the pinnacle of success, others as a stepping stone; the position may be seen as earned, as fallen-into, or as something else. It is of note to study what influence West Virginia and Appalachian culture have in how the women view their career paths.

RQ2: How do top female editors at West Virginia newspapers address the role of their region’s culture in shaping their career paths?

METHOD

This research employed grounded theory, which aims to develop a theory from interview-generated data (Glaser & Strauss, 1967). Interviews with top-level female editors in West Virginia were conducted in order to develop a theory about how they describe their paths to their current positions and how Appalachian culture played a role. Grounded theory was selected to allow the female editors freedom to answer and to let those answers inform their own theory. The result of this method was the development of a theory that explains a social process, in this case, how the participants viewed their career paths and how Appalachian culture has played a role in them.

Sampling

Grounded theory uses two types of sampling: selective and theoretical (Draucker, Martsolf, Ross & Rusk, 2007). Both were used in this research. Selective sampling occurred first, as is consistent with grounded theory (Thompson, 1990). Participants who are able to share experiences relating to the topic (i.e., female editors who work in West Virginia) were identified and contacted. Next came theoretical sampling, which is the process of selecting individuals who vary within the intended topic so as to further refine the emerging theory (Glaser & Strauss, 1967). This study sought interviews both from individuals who were originally natives of West Virginia as well as those who were not. Although we could have sampled women who occupied various levels of editorial responsibility, previous researchers have found that it is fairly common for women to reach lower-level editorial positions (e.g., Lee & Man, 2009), so this project focused on understanding the experiences of top female editors (a much smaller group).

Participants

Participants were drawn from current or former female editors at West Virginia newspapers in top decision-making roles, all of them either editor-in-chief or managing editor. Participants remained anonymous to help ensure honest, accurate data, as well as to focus on the patterns of behavior, rather than individual people. Ten participants were interviewed in all. Although this number may seem low, at the time of the study there were 23 women in West Virginia in such positions; as such the sample is 43% of the population, a healthy response rate. All participants were white and between the ages of 30 and 60. Although the lack of diversity may seem like a major limitation, white individuals make up more than 90% of the population in West Virginia (US Census, 2010).

Procedure

A series of open-ended interviews were conducted with each participant. Each lasted about an hour, and all were recorded, transcribed, and coded. Consistent with grounded theory methods, the constant comparative method of data collection and analysis was used (Glaser & Strauss, 1967). Constant comparative analysis is the process of collecting data and analyzing it simultaneously, as opposed to collecting all of the data and then analyzing it. As such, coding began after the first interview and guided interview questions in later interviews so that coding categories could be tested and the developing theory could be more fully identified.

Data analysis was performed on three different levels: open, axial, and selective. Open coding began after the first interview in order to help guide further data collection. At this stage, each sentence was coded. We looked for patterns to emerge and began to understand how participants’ experiences compared. Codes, such as hardworking and women’s issues (problems related to being a woman), emerged at this stage. Axial coding began after open coding. After the data was taken apart in open coding, axial coding involved reassembling the data according to the connections discovered between categories. For example, the insider/outsider category was created, which combined a number of smaller codes (i.e., barriers and integration). Selective coding was the final step in the data analysis. The purpose is to identify a main category that can explain the connections to each of the previously identified categories and codes. This main or primary category is the concept that unifies the study and is critical in theory creation.

RESULTS

This research revealed an interaction between two primary concepts: community and Appalachia. The first, community, is the keystone concept of how editors talk about themselves; Appalachia is related but more rooted in a specific sense of place. In the overlap of community and Appalachia, three supporting place characteristics emerged: boosts, challenges, and reciprocity. In addition, these female West Virginia editors saw their efforts to function as part of a community as strongly influenced by an insider/outsider effect that determined admission to place. This effect was described in terms of three areas: barriers, integration, and womanness.

Community and Appalachia

These two concepts worked in tandem: community as the broader idea, Appalachia as the sense of place specific to the region. The concept of community was not an exclusive one. Multiple communities existed for a given person, an observation that was particularly notable in discussion of the insider/outsider effect. The communities the editors described were defined by two main ideas: place functions and admission to place. Each is described below, but first, some discussion of Appalachia is necessary to understand the place in which these women function.

The women perceived Appalachia as inherently community-driven. When asked how they defined the region, they often did so in terms of the types of people (“friendly,” “willing to help”), the terrain (hills, natural) and debunking the stereotypes (uneducated, poor). Many believed that community was innately part of Appalachia, rather than acting as a separate concept. A recurring theme was that community exists in individuals, and discussions of Appalachia frequently shared this description. Community is what Appalachia does: “When I think of the [Appalachian] people, I think of people that are friendly, that will go out of their way to help certainly a neighbor in need or maybe even a stranger they’ve never met before” (Editor 2). According to this woman, the fact that West Virginians have had to rely on each other, in a state that has notoriously lacked technological advances to make communication with outsiders easier, has made community essential to the lives of West Virginians.

The other side of this, however, is that members of the Appalachian community may not be expected to ask for that relied-upon help. Editor 3, a West Virginia native, described her upbringing as an example of the traditions and behaviors that define Appalachia: “I grew up in a family that was very hardworking; a family of coal-miners. My mother was traditional … five kids, so she worked from sun up to sun down. That’s how you grew up. You didn’t call in sick for no reason; you didn’t take a day off.” In this community, work and endurance are expected; support is characteristic yet never requested. At the heart of the Appalachian community are three place functions: community boost, community complications, and reciprocity.

Community boost

This function describes the support one receives as part of the Appalachian community. Several of the editors described how their existing community roles helped them obtain their positions. Editor 5 is not from West Virginia, but “the fact that I had worked for a community newspaper in a metropolitan area [helped me get the job]. The [current newspaper and former newspaper] are very, very similar in their readership.” Demonstrating a solid place in her previous community allowed her editors to see that she was community-driven. When it came to advancing to an editorial position, she credited her community with helping: “People in the community I became associated with liked me and told my boss they liked me.”

This community boost can even overpower institutional decisions. In Editor 7’s case, when new management decided that she might not be the best person for the job, her community stood up for her. The people with whom she interacted on a daily basis weren’t the ones making the hiring decision, but because she had made such an impact on the community, they rallied to support her:

“This may sound like bragging but I know there were several people in the Community who told them – because I heard them with my own ears – ‘I don’t understand why you don’t make her editor … she knows how to do the job; she’s done it before.’ There were a few people who went to bat for me. That’s a nice thing about small towns.”

When these editors had a close connection with their communities, the communities vouched for them and encouraged their hiring or promotion.

Community complications

Community connections do not only serve as assets; these relationships and their expectations can create professional problems as well. One editor described the difficulty in balancing friendliness with objective journalism:

“They might think they deserve special treatment. Let something slide – ‘Don’t put me in the court news, I’m so and so.’ Well sorry. If I was in the court news, it would be in there. You can’t do that. I wrote my own traffic report one time about how I got into an accident [laughs].”

Another such complication is the perceived need to demonstrate authenticity. Despite her credentials as a lifelong resident, Editor 1 felt a need to make explicit her role as a local:

“When I was first editor of [the newspaper], the first week I wrote a column introducing myself. I talked about three steps to Kevin Bacon – three degrees of separation. … I wrote a column about that. Here’s who I am. Here is who my parents are, my siblings, any organizations. Now I challenge you to see how you can get connected to me in three steps. It was an instant way that [readers] could say ‘that’s so-and so’s sister in law, she can’t be that bad.’ ”

Even though she felt the need to demonstrate her role in the community explicitly, Editor 1 believed her relationships with the people in her community helped place her in a better position, more able to secure interviews and connect with people. It is true that any editor will benefit from such connections, but the implication of this and other examples is that in West Virginia, those who are not born into their connections may never truly earn them.

Regional longevity is also seen as valued in West Virginia. Editor 3 identified time as a factor in strengthening connections: “Three of our reporters have been here 20 years or more. People trust us; people talk to us.” That established role, she said, helped her achieve a potentially sensitive goal:

“We did a piece on coal towns. Did not have the best press from the outside previously. … We decided to focus one of our pride sections on that. A lot of older miners have passed on. We have found that people loved those days. So many told them had I not had family who grew up as coal miners … had I not understood it, they would not have been interviewed. They did not trust the media to portray it accurately. It does give the foot in the door sometimes. You have to maintain that trust.”

This example is instructive because, according to the editor, it is not her time spent as a local journalist that matters so much as her time as a resident. Once again, the revelation is not merely the common knowledge that a journalist’s time in a community will lead to stronger connections; it is her time spent there as a person, and even her family’s time, that determines her level of access. The implication is that in West Virginia, the community is treated as an entity that can reward or punish, and the credentials needed to appease it may transcend even one’s own lifetime.

Reciprocity

Many of the women editors noted that while community is vital to the newspaper, the newspaper is also an important part of the community. The two work in conjunction. In terms of reciprocity, the newspaper gave the community as much as, if not more than, the community gave the newspaper.

Reciprocity may exist at the group and individual level. Editor 10 described a series of fundraisers in which her newspaper helped raise tens of thousands of dollars in a weekend. The newspaper helps sponsor a number of events that give back to the community, enriching its position and standing. As for smaller interactions, Editor 7 said it is typical for community members to stop into the newsroom, sometimes with news tips but other times just to chat (or complain). It’s not always conducive to work, but she described it as a necessary part of the newspaper’s role in the community:

“We have a couple people who come in here to just chit chat. Sometimes, I’m sitting here looking at my watch thinking ‘man I have a lot to do.’ That’s all part of it. The open door policy is very important.”

Editor 7 stated that the smaller newspapers work hard to get the community the news it needs and wants:

“Community newspapers must do everything – can only get community news here. With the small town papers, the readers get something they can’t get anywhere else. And that’s reliable community news. Whether it’s the trial of the person or this business that you, or the gentleman up the road who grew a tomato that looks like a duck, it’s stuff that you can’t get on CNN.”

Whether it is informational or financial, the editors see the newspaper-community relationship as important. The newspaper aims to be part of the community and deliver necessary information, and the people in the community rely on the newspaper not only for information but for helping with local events. The relationship becomes a two-way street in which both are important to their respective communities. The sense of place within those communities, however, comes with certain guidelines for admission, and this is the realm of the insider/outsider effect.

Insider/Outsider Effect

Most of the editors presented an insider/outsider theme. In the geographic sense, insiders tended to be from West Virginia or the area they specifically cover. Outsiders were not and thus were typically not fully accepted into a community. If one is from West Virginia, the view was that one is accepted more readily by natives. Editors who are not from West Virginia felt the effects of being an outsider. This makes a community operational – being inclusive and exclusive – and helps define who is and who is not Appalachian. In addition to West Virginian status, the concept also includes those with differing values or (less-common) sex.

Barriers

Those who believed they were perceived as not West Virginian (even if they were) were often skeptical of that perception ever changing. Editor 5 said so frankly: “I will never be part of this community. I will always be an outsider. I haven’t been from around here.” She’s also seen her experiences mirrored in others.

“I have a friend who has since moved away. She’s lived here for a while. We kept trying to convince her to run for public office. She would say, ‘You know just as well as I do, just because I wasn’t born here, I don’t have a snowball’s chance.’ And she’s right.”

Editor 5 said she would never consider running for office for this same reason: “People respect me and like me, and respect what I do, but I’m not from around here. I’m not even from West Virginia.”

Geographic outsiders talked about what they perceived as the rules for being seen as part of the community. One of these is time-based: how long one has been part of the community. Editor 5, a non-native, said she’d once heard it said that a family needed to live in West Virginia for three generations to be accepted. “If I was from [a city in West Virginia] or some place like that, that would be OK. I would only have to be here for two generations [laughs].” Even living in some part of the state may have been beneficial to her to break down that insider/outsider theme that so many non-West Virginians find themselves experiencing. Editor 9, another non-native, also referred to a time-based standard, but she believed her time spent in the state may qualify her to be more West Virginian.

“I’ve been here for 20 years. I’m accepted, I think. And I think because we came in the way we did where we were connected to a family that had been here too, it helped us. But there definitely is a stigma against transplants.”

In essence, being from West Virginia – even if it is not the part in which the editor is working – is better than not being from West Virginia at all.

Integration

As the editors attempted to assimilate into their chosen communities, they tended to internalize what the community values in order to be in touch with its needs. Editor 6 described the successful transition of another (male) outsider editor at her former newspaper: “He came from a rural area, similar to West Virginia … but [had a] willingness to learn about West Virginia.” Being accepted by the community helps one to become an “insider,” and a visible desire to become an “insider” is necessary. Some editors noted that the community changed their own values as they adapted to what it wanted and needed from its local newspaper. Part of adapting to a new place is learning to value what the community values:

“[Working at this newspaper] made me think of news in a different way – what’s important to these people? They like their community parades, events, they love their town … [I] began to value what they value. The community changed my own values. I just realized I had to start looking at news differently; it was no longer about what seems the most – not newsworthy – everything in that town is newsworthy to those people – it was about what people cared about.” (Editor 6)

When editors become part of the community, they often remain because they enjoy that acceptance and those community values. Editor 10 was interested in staying in her community because after she came to the area and got involved, and she said she couldn’t see herself anywhere else. Editor 7 kept her office door open so that members of the community could stop in. Her genuine listening and care about her community’s thoughts encouraged more visits from the community, which led to trust and acceptance. “Once they saw that I cared about what they were saying, it changed some attitudes,” she said. “I want to know what they care about because that’s what I care about.”

By these accounts, visible presence and desire are necessary ingredients of community integration. It was important for them to become part of their communities and begin to value what those communities valued. In order to truly become part of the community, they needed to embody those traits that were valued; to become part of the community, they had to become the community.

Womanness

A final component of the insider/outsider concept is one distinct to these female editors: Being a woman in a traditionally male role. While the women did not actively frame their gender group as a community, they provided examples that showed its influence on their path. They tended to describe themselves as outsiders attempting to seek entry into a male community, which in and of itself shows the women as part of their own outsider community.

The women provided multiple examples where they believed they were treated differently (and less respectfully) by readers, colleagues, and superiors for being women. Editor 3 recounted an incident where a reader did not believe a woman had the final say at the newspaper:

“In my first year, I had a gentleman up here who was old-school, you know, who wanted to publish a religious announcement and wanted to publish it as a letter to the editor. I’m trying to tell him he has to write something if he wants it to be a letter to the editor. Finally, he says, ‘Why can’t I talk to the man?’ I just looked at him and said, ‘You are talking to the man.’”

Editor 7 had a more severe incident where she believes she essentially lost her job because she was a woman when a new boss came to town and didn’t see women as managerial leaders. Because Editor 7’s new boss did not even have a conversation with her before announcing to a male coworker that she would no longer have her job, Editor 7 reasoned that he was uncomfortable with having a woman in that role. He complimented the accolades and coverage the newspaper had been involved with, but in Editor 7’s eyes, noticing that a woman was in charge tainted his vision for the newspaper. Many of the women described similar accounts in which they felt they were being treated differently; in nearly all cases, they noted it was never explicitly stated that the treatment was due to the fact that they were women.

Outsiders need proof – be it time worked at the publication, being born in the right state, or respect from readers and coworkers – to cross barriers and become insiders. Female editors tended to think they needed an extra level of proof beyond those every West Virginia journalist has to endure. Many of the editors read between the lines to describe the sex-related issues they faced from coworkers. “I do think we do have some difficulties, especially in the workforce,” Editor 8 said. “In my experience, I have dealt with some [coworkers] that are hard to get along with and that don’t want to help. I don’t know if it is because I am a woman, but it seems that way sometimes.”

While some of the women were reluctant to address their sex in terms of their career, their responses show it has played a role in their experiences as editors. It seems as though the women have an unstated insecurity about their sex in a male-dominated work environment, one based on a presence they may not have concrete evidence of, yet perceive nonetheless. This sense is supported by its recurrence across interviews, but the non-explicit nature of the reported examples also suggests that many editors have developed a sense for such interactions. As much as their sex may affect some coworkers, it seems as though it also inhibits the editors themselves.

DISCUSSION

This study focused on the role of Appalachian culture in the career paths of top female editors in West Virginia. A main expectation, based on the traditionally male culture of American newsrooms and the low proportion of women in top positions, was that women would describe an outsider perspective based significantly on their sex. The insider/outsider effect was indeed described as significant, yet the role of sex played a distant second to that of membership in the Appalachian community. The sense of community they described was found in functions of community boosts, complications, and reciprocity. It was tempered by their various insider and outsider statuses, drawing from barriers, integration, and womanness. The result is a balance of places and roles the editors constantly returned to in their descriptions. Awareness of place and one’s admission to place defines the editors’ roles in their communities.

Working in an Appalachian Community

The women generally believed that living in a community that relies heavily on interpersonal relationships has benefited their careers. Although West Virginia, and much of Appalachia, tends to lag behind the national average in technological advancement (Partridge, Betz, & Lobao, 2012), the editors frequently characterized that lag as contributing to the sense of community found in Appalachia, bringing about a sense of closeness, dependence, and a need to work together. Essentially, the lack of assets was presented as an asset. Further, editors at smaller newspapers must be equipped to tell a range of stories on the local level because they are the only ones capable of doing so (Kirkpatrick, 2001). Editor 2 said that her small staff has to be well-versed in writing, social media, and advertising, and Editor 3 explained that with a handful of staff, it is necessary for each writer to produce as many as seven stories per day to fill the newspaper. Metropolitan newspapers do not take on community news, so the community relies on the newspaper as much as the newspaper relies on the community.

The emphasis on the average American is typical of community newspapers (Garfrerick, 2010), and one of Gans’ (1979) news values. This may not seem distinctive to Appalachia, but several editors described an emphasis on the average and regional that superseded other criteria of newsworthiness: Editor 6, for example, noted that zoning stories were so important in her community that they came before events that some would consider more important, such as a former president coming to town. Many of the editors placed themselves in that “average American” role as well, noting how their place in the community – whether regional, within the newspaper, or with other organizations – helped lead to their current positions. Previous research has suggested female editors need to be involved with the community, and although these women were not hosting bake sales, they attended community events and helped raise money to give back to their community. Regular demonstrations of averageness and belonging seem a necessary part of the women’s careers.

Weekly papers in much of Appalachia tend to serve less affluent and less educated communities (Cross, Bissett & Arrowsmith, 2011), characteristics that may be involved in the hesitancy to accept outsiders, both geographically and those who may be more affluent or educated than the typical community member. Their protection of what and whom they know helps determine admission into individual communities. The female editors have internalized many of the qualities necessary to bridge that insider-outsider gap and become part of their community. Community newspapers have to provide information on local and regional events as well as social issues and more (Campbell, Smith & Siesmaa, 2011). In order to be one with the community, the editors have internalized those values, often to the extent that whatever is important to the community becomes personally interesting to many of the editors.

Although many of the editors were hesitant to describe gender-related issues they experienced ascending the editorial ranks, the examples they did give illustrated issues Elmore (2007) discussed: when women serve in editorial roles, it is sometimes at the cost of respect in the newsroom. Editor 5, for example noted how new management had planned to dismiss her before even having a conversation with her, a decision she suspected was due to her sex (the new manager didn’t know much about her, the newspaper had been doing well, and her second-in-command, a man, assumed the position immediately). Ross (2001) found most newsrooms still tend to be patriarchal, with some women still perceiving sex-based bias against them, and Walsh-Childers and Chance (1996) found women were often passed over for promotions in favor of men who were equally or less qualified, relegating qualified female editors to lower-level positions. The women in this study were rarely definite in claiming substandard treatment due to their sex, but considering culture described in the literature, it is not difficult to understand why they might perceive discrimination.

Model

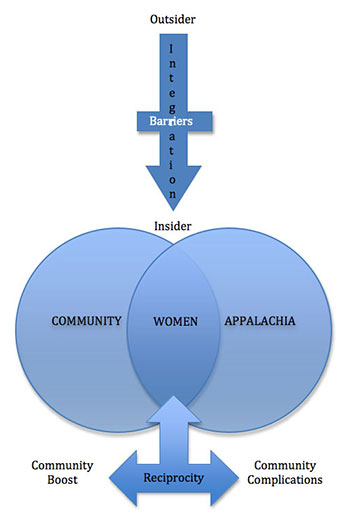

The following model describes the functions of and effects on community in Appalachian culture. Models are a necessary product of Grounded Theory and provide the method with explanatory power (Glaser & Strauss, 1967). Community’s overarching concept of a relationship among a group of people is embodied in two main concepts: place (Appalachia) functions and admission to place (the insider/outsider effect).

As part of Appalachia, the women made choices that influenced their role within the community. Based on their experiences, a strongly integrated community role might be expected to produce both greater assets (“community boost”) and greater drawbacks (“community complications”). The give-and-take relationship of newspaper and community (“reciprocity”) attempts to balance these two functions. Where the above concepts describe what a community is and does, the insider/outsider effect deals with individuals: Who is and is not part of that community, how one can become a part, and what stands in one’s way.

Through a “route to citizenship” of Appalachia, the model (Figure 1) illustrates the interaction of specific community variables. The women are a particular group that stands at the intersection of community and Appalachia. From this intersection flow the functions of community boost and community complications; the two are linked through the reciprocity function. The insider/outsider effect acts upon the women, who in addition to regional outsider factors, must deal with the additional outsider status of being a woman in top editorial roles traditionally filled by men. These and other barriers stand on the integration arrow, the “road to citizenship” for a given community, and are enforced by the insiders of that community. They may be surmounted via bonds, relationships, and longevity. Integration, in turn, determines the boosts and complications they may experience. The relationship is therefore a circular one: Once one becomes an insider, one becomes a part of Appalachia with a role and an expected reciprocity.

FIGURE 1: A PROPOSED MODEL OF COMMUNITY FUNCTIONS AND ADMISSION.

This particular model is distinct to Appalachia because it specifically characterizes concepts related to this particular region by way of admission standards related to the culture. For example, specific barriers to an Appalachian community include not originating in the specific area in which one works; the same may not be true (or as significant) elsewhere. With adjustments based on similar interviews, however, the model could be expanded to other groups.

The model can explain community’s vital part in rural journalism. With community being the central focal point, areas of place and admission help explain its standards. The model can break down these factors’ roles in the community newsroom, and whether they are overall beneficial or detrimental. The reciprocal relationship requires one to understand a place to cross the insider/outsider barrier at which point one becomes a part of that place with new roles and responsibilities.

CONCLUSION

Although the women in this study vary by their involvement in various communities, they all share that certain relationships have played a role in both the Appalachian culture as well as their career paths as editors in West Virginia. The relationships the women have encountered within the culture have helped them achieve their current positions. The strong ties of community within Appalachia helped shape their values and inclusion within the culture.

Some limitations were involved in this research. Sex did not seem to enter into the equation often, whether because it was not relevant or because of a reluctance to speak on the subject. Other limitations are the focus on small, community newspapers: Women working near larger West Virginia cities may have significantly different experiences. The results are not intended to be generalized to West Virginia or Appalachia, but they do describe the experiences of the women who work there and attempt to understand them as a group. With the infrequent references to the role of sex, future work might compare interviews with men in the state to give a more comprehensive view of the Appalachian journalist’s experience. Further study of why women may choose not to speak about their sex when viewing their career paths may be of interest to future research, which might also consider whether men choose to speak about their sex when describing their career paths. Further research might also be replicated with other underrepresented women in journalism.

The model is a blueprint for how relationships function in community journalism. It is beneficial to see how any community – physical, interest or relationship – functions and accepts members. It can be applied to various situations: workplace environments, interest groups, family dynamics and more. Any community that has relationship inner-workings can look to the model to apply individual characteristics and see how the community functions and accepts new members.

Discovering how female editors in Appalachia see themselves has been unexplored territory. In general, this segment of the population is not studied as often as others, perhaps in part due to that insider/outsider effect. Becoming aware of what role the women see their culture playing in their career paths can help explain both Appalachia and the distinctive strengths and challenges of community journalism.

WORKS CITED

- American Society of Newspaper Editors (2012). Newsroom employment census. Retrieved January 24, 2012, from http://www.asne.org

- Armstrong, C.A. (2014). Media Disparity: A Gender Battleground. Lexington Books.

- Beasley, M.H., & Gibbons, S.J. (1993). Taking their place: A documentary history of women and journalism. Washington, D.C.: American University Press.

- Bradshaw, K. Foust, J. & Bernt, J. (2005). Local television news anchors public appearances. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 49(2), 166-181.

- Bunch, W. (2008). Disconnected. American Journalism Review, 30(4), 38-45.

- Campbell, C., Smith, E., & Siesmaa, E. (2011). The educative role of a regional newspaper: Learning to be drier. Australian Journal Of Adult Learning, 51(2), 269-301.

- Clark, A., & Hayward, N. M. (2013). Talking Appalachian: Voice, identity, and community. Lexington; Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky.

- Craft, S., & Wanta, W. (2004). Women in the Newsroom: Influences of female editors and reports on the news agenda. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 81(1), 124-138.

- Creedon, P.J. and Cramer, J. (2007). Women in Mass Communication, Third Edition. Sage.

- Cross, A., Bissett, B., & Arrowsmith, H. (2011). Circulation patterns of weekly newspapers in Central Appalachia and Kentucky. Grassroots Editor, 52(3), 4-8.

- De Bruin, M. (2000). Gender, Organizational and Professional Identities in Journalism. Journalism 1, 217-238

- Downie, L. and Schudson, M. (2009). “The reconstruction of American Journalism.” Columbia Journalism Review, 28-51.

- Draucker, C., Martsolf, D., Ross, R. & Rusk, T. (2007). “Theoretical sampling and category development in grounded theory” Qualitative Health Research 17(8), 1137-1148.

- Enda, J. (2002). Women journalists see progress, but not nearly enough. Nieman Reports, 56(1), 67.

- Elmore, C. (2007). Recollections in hindsight from women who left: The gendered newsroom culture. Women & Language, 30(2), 18-27.

- Everbach, T. (2006). The culture of a women-led newspaper: An ethnographic study of the Sarasota Herald-Tribune. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 83(3), 477-493.

- Gans, H. J. (1980). Deciding What’s News. London: Constable.

- Garfrerick, B. H. (2010). The Community weekly newspaper: Telling America’s stories. American Journalism, 27(3), 151-157.

- Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory. Chicago: Aldine Publishing Co.

- Goward, P. (2006). 2. Gender and journalism. Pacific Journalism Review, 12(1), 15-19.

- Kian, E. M., & Hardin, M. (2009). Framing of sport coverage based on the sex of sports writers: Female journalists counter the traditional gendering of media coverage. International Journal Of Sport Communication, 2(2), 185-204.

- Kirkpatrick, R., (2001). Are Community newspapers really different?, Asia Pacific Media Educator, 10, 16-21.

- Lee, P., & Man, Y. (2009). Breaking the “glass ceiling” in the newsroom: The empowerment experience of female journalists. Conference Papers — International Communication Association, 1-47.

- Lewis, N. P. (2008). From cheesecake to chief: Newspaper editors’ slow acceptance of women. American Journalism, 25(2), 33-55.

- Lohmann, R. A. (1990). Four perspectives on Appalachian culture and poverty. Journal of the Appalachian Studies Association, 2, 76-91.

- Mills, K. (1998). A Place in the News. New York: Dodd, Mead & Co.

- Morton, J. (2009). “Not Dead Yet.” American Journalism Review, 48.

- Partridge, M. D., Betz, M. R., and Lobao, L. (2013). Natural Resource Curse and Poverty in Appalachian America. American Journal of Agricultural Economics 95 (2), 449-456.

- Reed, S. E. (2002). The Value of Women Journalists. Nieman Reports, 56(1), 63.

- Riggio, R. (2010). Do men and women lead differently? Who’s better? Psychology Today.

- Rosener, J. (1990). How women lead. Harvard Business Review, 68(6), 119-125.

- Ross, K. (2001). “Women at work: Journalism as an engendered practice,” Journalism Studies, 2(1), 531–544.

- Smith, K. and Wiltse, E. (2005). “Rate-setting procedures for preprint advertising at nondaily newspapers.” Journal of Media Economics, 18(1), 55-66.

- Tang, M., & Russ, K. (2007). Understanding and facilitating career development of people of Appalachian culture: An integrated approach. The Career Development Quarterly, 56(1), 34-46.

- Thompson, J. (1990), Hermeneutic enquiry. In E. Moody (Ed.), Advancing nursing science through research (pp. 223-280). London: Sage.

- Toegel, G. and Barsoux, J. (2012). Women leaders: The gender trap. The European Business Review. Retrieved from http://www.europeanbusinessreview.com

- Walsh-Childers, K., & Chance, J. (1996). Women journalists report discrimination in newsrooms. Newspaper Research Journal, 17(3/4), 68-87.

- West Virginia Press Association (2012). West Virginia Press Association Newspaper Directory. 1-36. Retrieved from http://www.wvpress.org/images/Directory/2012/2012 Directory_small_r.pdf

About the Authors

Candace R. Nelson is a graduate student at the Reed College of Media, West Virginia University.

Dr. Bob Britten is an assistant professor at the Reed College of Media, West Virginia University.

Dr. Jessica Troilo is an assistant professor of child development and family studies in the Department of Technology, Learning, and Culture at West Virginia University.

nelson-cj2015