Marcus Funk

Computerized content analysis software, or CATA, offers intriguing insight into the publication of normative deviance on the websites of American community and non-local newspapers. CATA of news factors, ANOVAs, and Pearson’s correlations indicate that community newspaper websites remain “relentlessly local,” but are otherwise as focused on normative deviance as metropolitan and national publications. Put another way: Once localness is established, online community newspaper content is statistically indistinguishable from online metropolitan and national newspaper content.

Media sociologists are fond of theoretical models that analyze and describe journalistic behavior as a highly routinized group mentality (Gans, 1979; Shoemaker & Reese, 1996; Shoemaker & Vos, 2009; Sigal, 1973; Tuchman, 1978; White, 1950). One such theoretical model, gatekeeping theory (Lewin, 1947; White, 1950), has evolved into a consideration of normative deviance (Jong Hyuk, 2008; Shoemaker, 1996; Shoemaker, Chang, & Brendlinger, 1987). The concept is twofold. First, journalists construct news around events, behaviors, ideas, or groups that break established social rules or norms. The goal is to establish potential threats to either the physical security or ideological status quo of the community; this behavior is rooted in a basic sociological need for safety and security (Shoemaker & Vos, 2009). Second, gatekeeping theory assumes media practitioners have little practical interaction with media audiences, and thus little public input into news creation (Shoemaker & Vos, 2009). This line of inquiry intersects with two intriguing concepts in communication research.

The first concerns the news factor approach, largely pioneered in Europe (Badii & Ward, 1980; Eilders, 2006; Galtung & Ruge, 1965; Joye, 2010; Kepplinger & Ehmig, 2006), which can effectively measure deviance. Bridges and Bridges (Bridges, 1989; Bridges & Bridges, 1997) argue that particular news factors appear in a wide range of American media. Second, audience interaction can be easily measured via American community newspaper websites; these publications are famous for consistent and strong ties to the opinions, needs, concerns, and interests of local communities (Burroughs, 2006; Funk, 2013b; Garfrerick, 2010; Hansen, 2007; Lauterer, 2006; S. C. Lewis, Kaufhold, & Lasorsa, 2009; Reader, 2006). Studying how community and non-community newspapers utilize those news factors on their websites would provide intriguing insight into gatekeeping theory, normative deviance, and the study of community news.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Gatekeeping Theory & Normative Deviance

Gatekeeping theory evolved from a wartime food consumption study by Kurt Lewin (1947) and subsequent adaptation to communication studies by David Manning White (1950), who found that a newspaper wire editor named ‘Mr. Gates’ made both objective and subjective decisions about what news to publish. While White speculated that Mr. Gates’ individual preferences influenced his editorial choices, further research indicated that journalists adhere to highly socialized and routinized patterns common throughout the journalism industry (Bleske, 1991; Bowman, 2008; Cassidy, 2006; Gans, 1979; Gieber, 1956; Hirsch, 1977; Shoemaker & Reese, 1996; Sigal, 1973). Individual choices matter little, these theorists argued, because a journalist’s demographic identity is secondary to entrenched journalistic standards and a largely inflexible conceptualization of ‘news.’

One explanation for that homogenization is normative deviance (Miliband, 1969; Paletz & Entman, 1981; Shoemaker, 1984; Shoemaker & Danielian, 1991; Shoemaker & Vos, 2009), which argues that media homogenization is rooted in a psychological need for safety and stability. Media fill a primal need to monitor potential predators and default to the same basic patterns and trends in news coverage. In today’s world, a variety of real and imagined problems qualify as threats to either the personal safety of media consumers or the ideological status quo of society (Shoemaker, 1996; Shoemaker, et al., 1987). For example, violent behavior among anti-abortion protestors has been associated with greater news coverage than ordinary demonstrations or rational political discourse concerning abortion (Boyle & Armstrong, 2009). Socialist electoral candidates are considered newsworthy threats to the status quo (Daley & James, 1988), deviant events concerning clergy are ‘triggers’ for inter-media agenda setting (Breen, 1997), and deviant news literally drew eyeballs in an online eye-tracking experiment:

Watching the environment enables human beings to run away from or fight against threatening events. Those who monitor their surroundings carefully can adapt themselves to the environment better than those who do not monitor their surroundings. According to Shoemaker [1996], this biological instinct to monitor the surroundings accounts for human beings’ interest in news.” (Jong Hyuk, 2008, p. 42)

Shoemaker and Vos (2009) make two further stipulations: Deviance is derived from a lack of interaction between news producers and news audiences, and that deviance can effectively be measured through the study of news factors.

News Factors

News factors research focuses on condensing news articles into common, discreet pieces; this approach lends itself well to the study of normative deviance, as those individual pieces can serve as scales for deviant content.

The news factor approach stems from a pivotal study by Johan Galtung and Mari Ruge (1965), who analyzed coverage of three overseas crises in four Norwegian newspapers and outlined 12 ‘news factors’ common to crisis coverage: frequency, threshold, unambiguity, meaningfulness, consonance, unexpectedness, continuity, composition, reference to elite nations, reference to elite people, reference to persons, and reference to something negative. They found that the more factors a potential news item contained, the more likely that item would receive coverage (Galtung & Ruge, 1965).

Replications abound. Harcup and O’Neill (2001) found the majority of those 12 factors applied to daily news coverage in United Kingdom newspapers; unambiguity was particularly common, although the framework had some difficulty describing entertainment news, references to sex or animals, or news motivated by a photograph. Joye (2010) refocused Galtung and Ruge’s (1965) study from crisis news to disaster news in Flemish newspapers and found proximity, geographically and culturally, as the predominant motivator for coverage of European or western disasters and marginalized news coverage of Asian, African or Latin American disasters. Kepplinger and Ehmig (2006) argued that news factors could serve predictive purpose rather than simply offering post-production illustrative detail, while Lewis and Cushion (2009) found breaking news so prevalent on 24-hour British television news networks that factors of ‘unpredictability’ often usurped ‘predictability;’ breaking news can be banal, in a sense, as long as it was current first and foremost. Of note, too, are considerations of Islamic religious values serving as news factors in Arab newspapers (Elliott & Greer, 2010; Mowlana, 1996). Alternate sets of factors have evolved as well (Corrigan, 1990; Gladney, 1996; Schulz, 1976), and as previously mentioned, Bridges and Bridges (Bridges, 1989; Bridges & Bridges, 1997) studied proximity, prominence, timeliness, impact, magnitude, conflict and oddity.

Community Journalism

What distinguishes community journalism as a genre, and as a relatively stable market product, is its extant and explicit focus on a local community, local readers, and local issues. Scholarship has repeatedly identified the ‘relentlessly local’ focus of community journalism (Lauterer, 2006), which are commonly operationalized as publications with less than 50,000 regular circulation. Such publications are principally devoted to local readers (Bowd, 2011; Funk, 2013b; Garfrerick, 2010; Hansen & Hansen, 2011), dedicated to helping local communities survive crises (Dill & Wu, 2009; Hansen & Hansen, 2012), interested in maintaining positive working relationships with local audiences and local elites (Donohue, Olien, & Tichenor, 1989; Reader, 2006), and have historically attempted to preserve community identity when faced with wartime atrocities or Cold War propaganda (Bishop, 2009; Carey, 2013).

As Gene Burd (1979) has noted, however, “definitions of community [are] crucial to journalistic training, practice and performance. In fact, the separation of community from any type of journalism may be a contradiction” (Burd, 1979, p. 3). This mirrors arguments by Benedict Anderson (2006) that community and news media are co-constructed and intrinsically inseparable. This expands the potential definitions of ‘local’ and ‘community journalism’ into new and niche markets, both on and offline. Community news media catered to the online role playing realm of Second Life (Brennen & dela Cerna, 2010), niche homosexual media (Cover, 2005), and local health activism publications (McAlister & Johnson, 2000). American community journalism also has been suggested as a model for media development in China (Lauterer, 2012). The definition of ‘community journalism,’ even, is flexible and more closely rooted to community service than any particular variety of localness (Lowrey, Brozana, & Mackay, 2008).

Research Questions

Two primary research questions consider variance of news factors across circulation categories and potential correlations between news factors. These RQs utilize terms that will be operationalized in the methodology section, along with an exploration and literature review of computerized content analysis.

RQ1: How does the publication of deviant, social significance, and egalitarian news factors vary across the websites of American community weekly, community daily, large daily, and national daily newspapers?

RQ2: How are deviant, social significance, and egalitarian news factors correlated with circulation size on the websites of American community weekly, community daily, large daily, and national daily newspapers?

Methodology

Content analysis is the systematic, inter-subjective study of content which is extant, and absent, within a media text. It is typically “systematic, objective, quantitative analysis” (Nuendorf, 2002, p. 1) that “limits itself to the produced content alone and draws conclusions based on what is there” (Poindexter & McCombs, 2000, p. 188). The goal is the valid and reliable translation of media content into useful statistical data. Traditionally, this has involved methodological categorization of data in media texts by trained coders following a strict codebook to derive quantitative data (Krippendorff, 2004; Nuendorf, 2002; Poindexter & McCombs, 2000; Weber, 1990). Computerized content analysis software, or CATA, essentially mechanizes and expedites the same process, concentrating both the strengths and weaknesses of the method.

CATA is capable of processing massive volumes of texts almost instantaneously, offering clear appeal to communication researchers; however, that analysis remains limited to what are essentially sophisticated word counts. Studies that rely upon even simple associations or context usually are beyond the software capabilities. One comparison of a traditional and CATA analyses concerning attribute agenda setting yielded vastly different results (Conway, 2006), and scholars are quick to advocate simplicity and specificity when dealing with computers (Krippendorff, 2004; Nuendorf, 2002).

The best method of ensuring validity uses words as the units of analyses. Proper computerized content analysis is achieved through the use of word dictionaries, essentially large word banks; the computer searches the text for every instance of every word in a word dictionary and groups those terms according to the researcher’s specifications.

For this study, word dictionaries will be constructed for each of Bridges and Bridges’ (Bridges, 1989; Bridges & Bridges, 1997) news factors; the program will count the frequencies of those words in the text, group those frequencies accordingly, and provide one frequency for each news factor in each category of media. The statistics are relatively simple. The challenge lies in ensuring that all relevant words are included and inappropriate words are struck from the word dictionaries; failing to do so could compromise the validity of the study. Once validity has been established, however, reliability is an extremely simple process. Computers cannot not be reliable. As a matter of design, they approach every data point in identical manner (Krippendorff, 2004; Nuendorf, 2002); there also is a substantial history of CATA in communication studies, particularly concerning rhetoric (Abdelrehim, Maltby, & Toms, 2011; Aust, 2004; Ballotti & Kaid, 2000; Cho et al., 2003; Conway, 2006; Crew & Lewis, 2011; Don, 2011; Gorton & Diels, 2010; Jarvis, 2004).

Operationalizations

Proper operationalization of terms is important for any study, but particularly a CATA analysis. As such, the first pertinent definition concerns normative deviance, as defined by texts on gatekeeping theory (Shoemaker & Vos, 2009).

Behavior, ideas, groups, or events are deviant when they break social rules or norms. Normative deviance is studied through news factors, a vein of academic research descended from the work of Galtung and Ruge (1965). Specifically, this study adopts and adapts Bridges and Bridges’ news factors (Bridges, 1989; Bridges & Bridges, 1997). This study organizes these factors into three categories that deserve explication here: Deviant Factors, Social Significance Factors, and Egalitarian Factors.

Deviant Factors: News that emphasizes aberration from regular routines or society, deviant news factors focus on various types of conflict and celebrity (i.e., prominence, conflict, oddity).

Social Significance Factors: Social significance factors relate to news factors that pertain to details of volume or scope. Not intrinsically deviant or egalitarian, they serve as descriptors of other deviant or egalitarian factors (i.e., impact).

Egalitarian Factors: News that emphasizes ordinary occurrence, egalitarian news factors focus on tangible details and regular interaction (i.e., timeliness, proximity).

The individual factors also deserve detailed operationalization. The deviant factors used here concern prominence, conflict, and oddity.

Prominence: Prominence refers to elite or infamous individuals, issues or institutions mentioned in an article. Prominence can be local, as in a mayor or a sports team, or non-local, as in a president or an ambassador.

Conflict: Conflict refers to open disagreement between persons, groups, animals or issues, against one another or nature. Clear, articulate opposition is required; however, conflict can be broadly defined. Conflict includes elections, sports games, crime, and severe weather.

Oddity: Oddity refers to news coverage which recognizes a rare or strange event or occurrence. Odd news is news because it is odd, not simply an unusual detail of regular news.

Social significance factors cannot be considered deviant or egalitarian. They are expressions of quantity or depth that enhance, augment, magnify, or devalue deviant or egalitarian factors. Originally, following Bridges and Bridges’ (Bridges, 1989; Bridges & Bridges, 1997) framework, factors for impact and magnitude were adopted for social significance; ultimately, due to CATA complications, magnitude was dropped from the analysis.

Impact: Impact refers to the effect or consequence of a news story, either damaging or enhancing, massive or miniscule. It is akin to intensity. An article about major or minor freeway closures could have impact, as could coverage of cancer treatments, legislative hearings, or congressional elections.

Egalitarian news factors consider the tangible, ordinary, and normal. They are sometimes considered “contingent conditions” (Shoemaker & Danielian, 1991). Both timeliness and proximity were ultimately broken into sub-categories.

Timeliness: Timeliness refers to the currency of a news story. News content relating to an event that occurred fewer than two days prior to the publication, or forecasting a news event fewer than two days in the future, qualifies.

Proximity: Proximity refers to the local-ness of a news item. Articles that mention a location, event, individual or institution within the immediate coverage area of a newspaper (operationalized as within 20 miles) qualify as proximate.

The media under scrutiny also deserve definition. Indeed, “community journalism” suffers from more than a bit of ambiguity. The industry standard defines community newspapers as publications regular circulation of less than 50,000 (Lauterer, 2006). While there is worthwhile conceptual debate concerning the nature of ‘community’ and the relationship between physical and ideological community (Anderson, 2006; Burd, 1979; Lowrey, et al., 2008), this study utilizes conventional circulation size as an operationalization.

Community Weekly Newspapers: Weekly, local, for-profit, American newspapers with regular print circulation of fewer than 50,000 copies.

Community Daily Newspapers: Daily, local, for-profit, American newspapers with regular daily print circulation of fewer than 50,000 copies.

Large Daily Newspapers: Daily, for-profit, American newspapers with regular daily print circulation of more than 50,000 copies but fewer than 500,000 copies.

National Newspapers: Daily, for-profit, American newspapers with a regular daily print circulation greater than 500,000 copies.

Dataset

A framework of 125 American newspapers was used to establish a dataset: 40 community newspapers, 40 community daily newspapers, 40 large daily newspapers, and five national newspapers. Establishing geographic diversity ensured that geographic biases did not call results into question. Following in the footsteps of Reader (2006), who divided the United States into 14 geographic categories to derive a qualitative dataset of 28 newspapers, this study partitioned the United States into eight discreet regions based on common cultural, economic, and socio-political characteristics.

Each region was allowed five community newspapers, five community daily newspapers, and five large daily newspapers. The random selection process utilized a set of multi-sided dice to determine random starting points and publications. Publication frequency and circulation size were then confirmed through the Ulrich Periodic Index. This random sample accounted for 120 American newspapers stratified by circulation size and regional geography; this sampling was based largely on a previous study of community newspapers and Benedict Anderson’s theory of ‘imagined communities’ (Anderson, 2006; Funk, 2013a). The Funk (2013a) study used identical regional categories, a 120-newspaper sample, and served as the basis for the random dataset; the researcher updated and confirmed the circulation size and categorization in October 2012. Additionally, one national newspaper was chosen from five different regional categories. Random selection was employed in regions with multiple national newspapers.

The data collection process utilized a constructed-week format. Since some weekly newspapers publish online content once a week, data was never collected from the same publication more than once in any given week. The 125 newspapers were randomly sorted into five groups of 25 newspapers each. Five constructed weeks were designed over a nine-week period; technical difficulties resulted in rescheduling one data collection point during a tenth week. Data were collected between January and March 2013.

Data consisted of the three most prominent news articles on each news website. The full articles, headlines and subheadlines were copied and pasted into Microsoft Word. Bylines, authorship, and contact information was omitted. The Word documents were organized by group and circulation size category, and also included the day of the week and date in the document title (ie, ‘A.CW.Monday.1.1’ for a hypothetical data collected from community weekly newspapers in Group A on Monday, Jan. 1). There were a total of 375 articles downloaded each day per group and a grand total of 2,625 articles from newspaper websites.

Word Dictionaries

Word dictionaries were designed to be exhaustive and inclusive. They included any word that could qualify for each of the news factors, as well as different conjugations (i.e., conflict, conflicting, conflicted) and forms (i.e., violence and violent). Word dictionaries for prominence, conflict, oddity, and impact were straightforward but vast. Dictionaries for the remaining factors were more complex.

Proximity was split into two sections, general proximity and specific proximity. General proximity consisted of terms like ‘local’ and ‘area.’ Specific proximity was derived primarily through the website FreeMapTools.com, which constructed a transparent radius around each listed community in Google Maps; the map was then zoomed to a two-mile scale and scanned for any cities, towns, villages, or labeled neighborhoods located wholly or partially within the radius. The dictionary also included the name of the home community’s county, counties, parish, or parishes. Each category of newspapers had its own specific proximity dictionary; i.e., community weekly newspapers in the A group, or A.CW, had one dictionary, as did A.CD, A.LD, A.ND, B.CW, C.CW, and so on.

Similarly, timeliness was sub-divided into ‘recentness’ and ‘dates.’ Recentness contained words stating timeliness, such as ‘recent’ or ‘current,’ while dates was customized for each individual set of articles to include the date of publication as well as the two dates before and after (i.e., within the word dictionary itself, for hypothetical dataset A.CW.Monday.1.1, the dates dictionary would include ‘December = 30, December = 31, January = 1, January = 2, January = 3).

The final of Bridges and Bridges’ (Bridges, 1989; Bridges & Bridges, 1997) news factors, magnitude, is an expression of quantity that was ultimately abandoned. Although DICTION 6.0 can count quantitative figures, it cannot distinguish between numbers which are not expressions of quantity. It cannot tell the difference, for example, between the phrases ‘221 percent tax increase’ and ‘221 Baker Street,’ or between 5,125,555,555 people and the phone number (512) 555-5555. Efforts to engineer a solution were ultimately unreliable and unsuccessful.

A sample list of terms used in each word dictionary is available in Table 1. The construction of these dictionaries was conducted in Microsoft Excel. This enabled easy comparison and construction of dictionaries and an expedient search for duplicate entries. It was important to ensure that, for every dictionary but those designed for specific proximity, every word be included in only one dictionary. For specific proximity, it was acceptable if (hypothetically) Springfield, Massachusetts and Springfield, Oregon were in two different specific proximity dictionaries as only one specific proximity dictionary would be enabled at a time. However, it was important that ‘Springfield’ appear only once in each dictionary.

To ensure validity, the researcher solicited input and review from six graduate students and professors at a major research university. This process was theoretically analogous to inter-coder reliability procedures; while one individual may plan word dictionaries with validity errors, consultation with a group of researchers reduced the likelihood of improper inclusions or exclusions.

The final step imported each of the 26 dictionaries (prominence, conflict, oddity, impact, recentness, general proximity, and 20 dictionaries for specific proximity) into DICTION 6.0’s custom dictionary feature. Finally, the dates dictionary was adjusted manually prior to each individual analysis.

Once the word dictionaries were constructed, the analysis began. DICTION 6.0 computed means for each word dictionary for each Word document containing downloaded articles. Data were then processed and analyzed in Microsoft Excel and SPSS for ANOVA analyses and Pearson’s correlation analyses.

Finally, because the data analysis process utilized a multi-step and multi-platform process, the final ‘n’ in the SPSS analysis is only partially representative of the full dataset. SPSS processed what it considered 140 dense units of data – one unit for each document representing thousands of downloaded articles. One data unit represented DICTION 6.0 analyses of online news articles from community weekly newspapers in Group A, another for community daily newspapers in Group A, and so on. The number 140 misleads here as it represents only the final step in the data analysis process and understates the density of the dataset. As such, this study includes an n to represent the number of data points measured by SPSS and an n0 reflecting the number of articles and, thus, the true number of data points.

Table 1: Word Dictionaries

| DEVIANT NEWS FACTORS | |

| Prominence | Mayor, governor, president, senator, executive, elite, CEO, COO, reigning, actor, musician, singer, celebrity, athlete, professional. |

| Conflict | War, conflict, clash, spat, difference, disagreement, disparity, confrontation, violence, violent. |

| Oddity | Odd, strange, bizarre, unusual, uncanny, unnerving, rare, extraordinary. |

| SOCIAL SIGNIFICANCE FACTORS | |

| Impact | Impact, change, difference, meaningful, major, important, crucial, critical, altering, changing, ending, beginning, genesis, cataclysm. |

| EGALITARIAN NEWS FACTORS | |

| Timeliness | |

| Recentness | Yesterday, today, tomorrow, soon, lately, (Not: next, last.) |

| Dates | The specific dates for the date of data collection, two days previous and two days following, as well as the corresponding days of the week, for each set of articles. |

| Proximity | |

| General Proximity | Local, area, nearby. |

| Specific Proximity | The name of every city, town, village, or neighborhood within 20 miles of each newspapers’ home community, as well as the community’s county or counties, or parish or parishes. |

Results

Broadly, computerized content analysis found that circulation size plays no significant role in the use of deviant or egalitarian news factors, and a limited role concerning egalitarian factors. Put another way: Community weekly newspapers and national newspapers are equally focused on conflict, prominence, and oddity in their online news content.

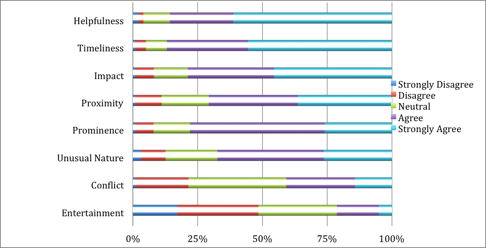

RQ1 asked how the publication of deviant, social significance, and egalitarian news factors varied across the websites of American community weekly, community daily, large daily, and national daily newspapers. ANOVA indicated that American newspapers of all circulation sizes demonstrated clear, unanimous consistency concerning deviant and egalitarian news factors. Variance for only one factor, specific proximity, was statistically significant (p < .001**, df = 3, n = 140, n0 = 2,625); smaller newspapers were significantly more likely to publish specific proximity factors than larger newspapers. Put another way: community newspapers were significantly more likely to publish the names of their home communities, and nearby communities, in their news coverage. The remaining factors saw no significant variation across circulation categories (see Figure 1 for means and ANOVA analyses).

Figure 1: Word Frequency Means of News Factors on Newspaper Websites by Circulation Category

RQ2 asked how deviant, social significance, and egalitarian news factors are correlated with circulation size on the websites of American community weekly, community daily, large daily, and national daily newspapers.

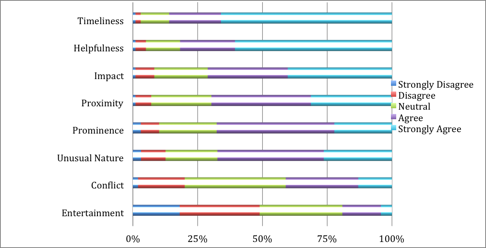

Pearson’s correlations were used to determine potential relationships between circulation size and use of deviant, social significance, and egalitarian news factors in online news. Analysis indicated only one pertinent significant correlation, between circulation size and specific proximity (r = -.342**, p < .001, n = 140, n0 = 2,625); the negative orientation indicates that the larger the circulation size, the lower the frequency of specific proximity. This is consistent with ANOVA analysis of the same data. The remaining factors had non-significant relationships with circulation size. Analysis also indicated a significant relationship between oddity and general proximity (r = .279**, p < .001, n = 140, n0 = 2,625). This relationship is not particularly relevant, but the full correlations set is reported here in the interest of comprehensiveness (see Figure 2 for correlation analyses).

Discussion

Data presented here indicate the spectrum of American newspaper websites remain predominately preoccupied with news about deviance. Deviance remains a constant focus in news construction, even among hyper-local community newspapers which are also focused on localness. The relationship between circulation size and geographic focus is not surprising; indeed, this is consistent with the editorial mission and business model of community journalism. It is surprising, however, that news content in hyper-local community newspapers is as focused on deviance as national media like The New York Times.

Figure 2: Pearson’s Correlations of Means Comparing Circulation Category and News Factors on Newspaper Websites

The weekly, hyper-local Weekly Observer is certainly concerned with local news about its home in Hemingway, South Carolina; The Los Angeles Times, conversely, is less concerned with news about Los Angeles and more devoted to major national and international news. Once that local focus is accounted for, however, there are no significant differences between the two concerning the remainder of their editorial content.

Put another way: If quantitative analysis had not measured for specific proximity and had instead been solely concerned with the use of deviant news factors, then the news content in The Weekly Observer and The Los Angeles Times would yield statistically identical results. Thus, the only important difference between community journalism news content and national journalism news content is a focus on localness – the “community” may generate differences in newspaper business models, but a pervasive industry standard on deviance clearly defines the “journalism” part, regardless of a publication’s circulation size.

These findings also speak to a remarkably high degree of media socialization across ostensibly diverse varieties of journalists, thus reinforcing media sociology and gatekeeping studies (Cassidy, 2006; Gans, 1979; Gieber, 1956; Lewin, 1947; Shoemaker & Reese, 1996; Shoemaker & Vos, 2009; Sigal, 1973; White, 1950). It also speaks to the prevalence of normative deviance in American media and the predictive power of news factor studies.

However, data also are contrary to gatekeeping theory’s stipulation that journalists default to news about deviance due to a lack of interaction with media audiences. Given community newspapers’ well established dialogue with local communities, it seems apparent that normative deviance is a foundational part of American news. It is not a construction of isolated journalists; instead, these data show normative deviance is independent of journalist-audience interaction.

This study identifies two major opportunities for future research. First, findings indicating that normative deviance is not the result of poor journalist and audience communication are a noteworthy repudiation of gatekeeping theory (Shoemaker & Vos, 2009). Deviance, instead, is a constant focus of American online news regardless of a newspapers’ circulation size. Why? Why do journalists who do have near constant communication with audiences remain focused on deviance, and what might interviews with those journalists and audiences reveal? Findings point to a need for better theoretical understanding and definition of normative deviance.

Second, as definitions of community and localness continue to evolve, it would be meritorious to consider how deviance applies to non-geographic community journalism. How might community media focused on particular ideological niches, professional trades, or sports teams incorporate normative deviance? Would they reflect a consistent focus on deviance, or not? Future studies could apply the frameworks used here to other varieties of community media.

Works Cited

- Abdelrehim, N., Maltby, J., & Toms, S. (2011). Corporate Social Responsibility and Corporate Control: The Anglo-Iranian Oil Company, 1933-1951. Enterprise and Society, 12(4), 824-862.

- Anderson, B. (2006). Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism (Revised Edition ed.). London: Verso.

- Aust, P. J. (2004). Communicated values as indicators of organizational identity: A method for organizational assessment and its application in a case study. Communication Studies, 55(4), 515-534.

- Badii, N., & Ward, W. J. (1980). The Nature of News in Four Dimensions. Journalism Quarterly, 57, 243-248.

- Ballotti, J., & Kaid, L. L. (2000). Examining verbal style in presidential campaign spots. Communication Studies, 51(3), 258-273.

- Bishop, R. (2009). “Little More than Minutes”: How Two Wyoming Community Newspapers Covered the Construction of the Heart Mountain Internment Camp. American Journalism, 26(3), 7-32.

- Bleske, G. L. (1991). Ms. Gates Takes Over. [Article]. Newspaper Research Journal, 12(4), 88-97.

- Bowd, K. (2011). Reflecting regional life: Localness and social capital in Australian country newspapers. Pacific Journalism Review, 17(2), 72-91.

- Bowman, L. (2008). Re-examining “Gatekeeping.” Journalism Practice, 2(1), 99-112.

- Boyle, M. P., & Armstrong, C. L. (2009). Measuring Level of Deviance: Considering the Distinct Influence of Goals and Tactics on News Treatment of Abortion Protests. Atlantic Journal of Communication, 17(4), 166-183.

- Breen, M. J. (1997). A cook, a cardinal, his priests, and the press: Deviance as a trigger for intermedia agenda setting. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 74(2), 348-356.

- Brennen, B., & dela Cerna, E. (2010). Journalism in Second Life. Journalism Studies, 11(4), 546-554.

- Bridges, J. A. (1989). News Use on the Front Pages of the American Daily. Journalism Quarterly, 66, 332-337.

- Bridges, J. A., & Bridges, L. W. (1997). Changes in News Use on the Front Pages of the American Daily Newspaper, 1986-1993. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 74(4), 826-838.

- Burd, G. (1979). What is community? Grassroots Editor, 20(1), 3-14.

- Burroughs, A. (2006). Civic Journalism and the Community Newspaper: Opportunities for Civic and Social Connections. Master of Mass Communication, Louisiana State University.

- Carey, M. C. (2013). Community Journalism in a Secret City. Journalism History, 39(1), 2-14.

- Cassidy, W. P. (2006). Gatekeeping Similar For Online, Print Journalists. Newspaper Research Journal, 27(2), 6-23.

- Cho, J., Boyle, M. P., Keum, H., Shevy, M. D., McLeod, D. M., Shah, D. V., & Pan, Z. (2003). Media, Terrorism, and Emotionality: Emotional Differences in Media Content and Public Reactions to the September 11th Terrorist Attacks. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 47(3), 309-327.

- Conway, M. (2006). The Subjective Precision of Computers: A Methodological Comparison with Human Coding in Content Analysis. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 83(1), 186-200.

- Corrigan, D. M. (1990). Value Coding Consensus in Front Page News Leads. Journalism Quarterly, 67(4), 653-662.

- Cover, R. (2005). Engaging sexualities: Lesbian/gay print journalism, community belonging, social space and physical place. Pacific Journalism Review, 11(1), 113-132.

- Crew, J. R. E., & Lewis, C. (2011). Verbal Style, Gubernatorial Strategies, and Legislative Success. Political Psychology, 32(4), 623-642.

- Daley, P. J., & James, B. (1988). Framing the News: Socialism as Deviance. Journal of Mass Media Ethics, 3(2), 37-46.

- Dill, R. K., & Wu, H. D. (2009). Coverage of Katrina in Local, Regional, National Newspapers. Newspaper Research Journal, 30(1), 6-20.

- Don, W. (2011). Jokes inviting more than laughter Joan Rivers political-rhetorical world view. Comedy Studies, 2(2), 139-150.

- Donohue, G. A., Olien, C. N., & Tichenor, P. J. (1989). Struture and constraints on community newspaper gatekeepers. Journalism Quarterly, 66(4), 807-845.

- Eilders, C. (2006). News factors and news decisions. Theoretical and methodological advances in Germany. Communications: The European Journal of Communication Research, 31(1), 5-24.

- Elliott, C. W., & Greer, C. F. (2010). Newsworthiness and Islam: An Analysis of Values in the Muslim Online Press. Communication Quarterly, 58(4), 414-430.

- Funk, M. (2013a). Imagined commodities? Analyzing local identity and place in American community newspaper website banners. New Media & Society, 15(4), 574-595.

- Funk, M. (2013b). The Next President is at the Front Door Again: An Analysis of Local Media Coverage of the 2012 Republican Iowa Caucus, New Hampshire Primary and South Carolina Primary. Community Journalism, 2(1), 26-48.

- Galtung, J., & Ruge, M. (1965). The structure of foreign news: the presentation of the Congo, Cuba and Cyprus crises in four Norweigan newspapers. Journal of International Peace Research, 1, 64-91.

- Gans, H. J. (1979). Deciding what’s news. New York, NY: Pantheon.

- Garfrerick, B. H. (2010). The Community Weekly Newspaper: Telling America’s Stories. American Journalism, 27(3), 151-157.

- Gieber, W. (1956). Across the desk: A study of 16 telegraph editors. Journalism Quarterly, 33(4), 423-432.

- Gladney, G. A. (1996). How Editors and Readers Rank and Rate the Importance of Eighteen Traditional Standards of Newspaper Excellence. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 73(2), 285-303.

- Gorton, W., & Diels, J. (2010). Is political talk getting smarter? An analysis of presidential debates and the Flynn effect. Public Understanding of Science.

- Hansen, E. K. (2007). Community insights on newspaper Web sites: What readers want. Paper presented at the Newspapers and Community-Building Symposium XIII, Norfolk, Virginia.

- Hansen, E. K., & Hansen, G. L. (2011). Newspaper Improves Reader Satisfaction By Refocusing on Local Issues. Newspaper Research Journal, 32(1), 98-106.

- Hansen, E. K., & Hansen, G. L. (2012). Community crisis and community newspapers: A case study of The Licking Valley Courier. Grassroots Editor, 53(3-4), 8-12.

- Harcup, T., & O’Neill, D. (2001). What Is News? Galtung and Ruge revisited. Journalism Studies, 2(2), 261-280.

- Hirsch, P. M. (1977). Occupational, Organizational and Institutional Models in Mass Media Research. In P. M. Hirsch, P. M. Miller & F. G. Kline (Eds.), Strategies for Communication Research (pp. 13-42). Beverly Hills, California: Sage.

- Jarvis, S. E. (2004). Partisan patterns in presidential campaign speeches, 1948-2000. Communication Quarterly, 52(4), 403-419.

- Jong Hyuk, L. (2008). Effects of News Deviance and Personal Involvement on Audience Story Selection: A Web-Tracking Analysis. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 85(1), 41-60.

- Joye, S. (2010). News media and the (de)construction of risk: How Flemish newspapers select and cover international disasters. Catalan Journal of Communication & Cultural Studies, 2(2), 253-266.

- Kepplinger, H. M., & Ehmig, S. C. (2006). Predicting news decisions. An empirical test of the two-component theory of news selection. Communications: The European Journal of Communication Research, 31(1), 25-43.

- Kim, H. S. (2012). War journalists and forces of gatekeeping during the escalation and the de-escalation periods of the Iraq War. International Communication Gazette, 74(5), 323-341.

- Krippendorff, K. (2004). Content Analysis: An Introduction to its Methodology (Second Edition ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Lauterer, J. (2006). Community Journalism: Relentlessly Local. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press.

- Lauterer, J. (2012). Toto, I don’t think we’re (just) in Kansas anymore: How U.S. community newspapers are serving as a model for China. Grassroots Editor, 53(3-4), 1-7.

- Lewin, K. (1947). Frontiers in Group Dynamics II. Channels of group life: Social Planning and Action Research. Human Relations, 1, 143-145.

- Lewis, J., & Cushion, S. (2009). The Thirst to Be First. Journalism Practice, 3(3), 304-318.

- Lewis, S. C., Kaufhold, K., & Lasorsa, D. L. (2009). Thinking About Citizen Journalism. Journalism Practice, 4(2), 163-179.

- Lowrey, W., Brozana, A., & Mackay, J. B. (2008). Toward a Measure of Community Journalism. Mass Communication & Society, 11(3), 275-299.

- McAlister, A., & Johnson, W. (2000). Behavioral Journalism for HIV Prevention: Community Newsletters Influence Risk-Related Attitudes and Behavior. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 77(1), 143-159.

- Miliband, R. (1969). The State in Capitalist Society. London: Wiedenfeld & Nicholson.

- Mowlana, H. (1996). Global communication in transition: The end of diversity? London: Sage.

- Nuendorf, K. A. (2002). The Content Analysis Guidebook. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Östgaard, E. (1965). Factors Influencing the Flow of News. Journal of Peace Research, 2(1), 39-63.

- Paletz, D. L., & Entman, R. M. (1981). Media, Power, Politics. New York: Free Press.

- Poindexter, P. M., & McCombs, M. E. (2000). Research in Mass Communication: A Practical Guide. Boston & New York: Bedford / St. Martin’s.

- Reader, B. (2006). Distinctions that Matter: Ethical Differences at Large and Small Newspapers. Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly, 83(4), 860.

- Schulz, W. (1976). Die Konstruktion von Realitat in den Nachrichtenmedien: Analyse der aktuellen Berichterstattung [The construction of reality in the news media. An analysis of the news coverage]. Freiburg: Alber.

- Shoemaker, P. (1984). Media Treatment of Deviant Political Groups. Journalism Quarterly, 61(1), 66-82.

- Shoemaker, P. (1996). Hardwired for News: Using Biological and Cultural Evolution to Explain the Surveillance Function. Journal of Communication, 46(3), 32-47.

- Shoemaker, P., Chang, T. K., & Brendlinger, N. (1987). Deviance as a predictor of newsworthiness: Coverage of international events in the U.S. media. In M. McLaughlin (Ed.), Communication yearbook (Vol. 10, pp. 348-365). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

- Shoemaker, P., & Danielian, L. (1991). Deviant Acts, Risky Business and U.S. Interests: The Newsworthiness of World Events. Journalism Quarterly, 68(4), 781-795.

- Shoemaker, P., & Reese, S. (1996). Mediating the Message: Theories of Influence on Media Content (2 ed.). White Plains, N.Y.: Longman.

- Shoemaker, P., & Vos, T. (2009). Gatekeeping Theory. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Sigal, L. (1973). Reporters and officials: The organization and politics of news-making. Lexington, MA: D.C. Heath.

- Smethers, S., Bressers, B., Willard, A., Harvey, L., & Freeland, G. (2007). Kansas Readers Feel Loss When Town’s Paper Closes. Newspaper Research Journal, 28(4), 6-21.

- Tuchman, G. (1978). Making News. New York: Free Press.

- Weber, R. P. (1990). Basic Content Analysis (Second Edition ed.). Newbury Park, CA: SAGE Publications.

- White, D. M. (1950). The ‘Gate Keeper’: A Case Study in the Selection of News. Journalism Quarterly, 27(3), 383-390.

About the Author

Dr. Marcus Funk is an assistant professor of journalism at Sam Houston State University.