Jeremiah Opiniano, Jasper Emmanuel Arcalas, Mia Rosienna Mallari and Jhoana Paula Tuazon

This case study examines the current state of community journalism in the Philippines. This paper builds from previous studies, especially those by Filipino community journalism scholar Crispin Maslog, on the community press in the Philippines. The focus of this paper is the community newspaper and online community news websites. This case study includes interviews with leading stakeholders in the community press sector of the country. Pertinent documents surrounding the community press were collected and analysed.

The Philippines is one of the freest press and media systems in the world. Amid the steep financial requirements associated with running a news organization (both for commercial and non-profit purposes), journalists from the Philippines have showcased areas of journalism that have made the country a global and regional model in this profession. One area of note is investigative journalism — especially done with limited aid from technology. At the first Asian Investigative Journalism Conference (AIJC) held in Manila (22 to 24 November 2014), the Global Investigative Journalism Network (or GIJN) commended the Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism (PCIJ) for pioneering efforts on investigative reporting in Asia.

This case study examines the current state of community journalism in the Philippines. This paper builds on previous studies, especially those by Filipino community journalism scholar Crispin Maslog (1967, 1971, 1985, 1993, 2012a), on the community press in the Philippines. The focus of this paper is on the community newspaper and online community news websites. This case study includes interviews with leading stakeholders in the community press sector of the country. Pertinent documents surrounding the community press were collected and analysed. The paper also collected some 100 community newspapers, with publication dates covering the year 2014, and analyzed their staff boxes in order to provide a snapshot of the editorial and administrative personnel of these community newspapers.

Another creation originating from the Philippines, in the late 1960s, is development journalism — “people-centered” reporting that is said to give “alert news audiences to development problems and open their eyes to possible solutions” (Chalkley, 1968). Following American influences, what also figured prominently in the Philippines is civic or public journalism, where the media in a democratic society not only inform the people but also engage citizens and stir public debate.

PCIJ’s focus is investigative journalism. For development journalism, sometimes referred to as “journalism with a purpose” (Maslog, 2012a), a defunct news service called DEPTHNews (Development, Economic and Population Themes News) run by the Manila-headquartered Press Foundation in Asia blazed the trail in producing development stories that were shared with mainstream news media in the Philippines and across Asia (Xiaoge, 2009; McKay, 1993). The non-profit Center for Community Journalism and Development (CCJD) collaborated with an association of newspaper publishers, the Philippine Press Institute (PPI), bringing civic or public journalism to communities outside of the Philippines’ capital region. CCJD was, in fact, the only foreign group featured in a list of resources on community journalism contained in the US-published book Foundations of Community Journalism (2011). The geographical reference to CCJD in the book is Southeast Asia.

Some scholars have noted that internationally, the Philippines also figures prominently in community journalism. Research on community newspapers from the Philippines had been recognized as among the first studies worldwide (Hatcher, 2012), with a study as early as a 1967 survey on the Philippine community press (in Maslog, 2012a). The Philippines is an archipelago with 7,107 islands and 79 provinces, many of which are not as economically robust as the seat of power, Metro Manila (or the National Capital Region). But the geographical dispersion of Filipinos became a natural setting for community journalism to thrive while Metro Manila houses nationally circulating newspapers and broadcast stations that have a nationwide reach.

Previously published studies on community journalism in the Philippines include qualitative profiles of community newspapers and their editors (Markham & Maslog, 1969; Maslog, 1971; Mejorada, 1990); the managerial aspects of publishing community newspapers (Maslog, 1985; 1993); ethical issues facing community journalists (Chua, 2012); and lately the welfare of community journalists given the spate of media killings hitting Filipino journalists nationwide (Braid, Tuazon & Maslog, 2012). While research on community journalism is slowly growing, international experiences and examples remain wanting for even the most basic documentation of how community journalism prevails in different countries (Hatcher, 2012).

This manuscript begins with a look at the role of the community press and of community journalists. Next, the authors present an updated status of the Philippine community press, including the current socio-economic and political challenges facing this sector of the mainstream news media. Finally, prospects on the immediate future of community journalism by Filipinos are presented.

THE PHILIPPINES: LOCAL ECONOMIC GROWTH AND NEWSPAPER PUBLISHING

This Southeast Asian archipelago has long been lagging behind neighbors in the region such as Singapore, Malaysia, Indonesia and Thailand (Virola, Astrologo & Rivera, 2010). However, since the global economic crisis in 2008, Philippine economic growth has been on the uptick — with analysts labelling the Philippines an “emerging economy” (Schuman, 2014). Government fiscal managers have reportedly done their job in maintaining solid macro-economic fundamentals (e.g. steady inflation, manageable levels of national debt vis-à-vis gross domestic product, combating corruption at national government agencies) (World Bank Philippines, 2014). Meanwhile, consumption continues to drive the economy; by sector, the Philippines is predominantly a service economy. Billion-dollar remittances from Filipinos working and living abroad have been a major economic resource — the number one source of revenue for the country. These economic developments in the last five to six years have prevailed despite slumping agriculture and a stagnant growth in the industrial sector.

Recent growth in the national economy may have cascaded into the country’s regions, affecting both urbanized and rural regions. The Philippine Statistical Authority, in 2013, said 13 of the 17 regions of the country are predominantly service-based; only one region, the Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (or ARMM, the country’s poorest region), is predominantly agricultural while three regions are predominantly industrial: Calabarzon (Region 4a, found east and south of Manila), the Cordillera Administrative Region (CAR, north of Manila), and Central Visayas (in the central islands of the country) (Philippine Statistical Authority, 2013). All regions of the country are steadily growing in terms of their gross regional domestic production.

Overseas remittances sent to families of Filipinos abroad residing in these Philippine regions have also driven regional and local economic growth (Institute for Migration and Development Issues, 2008). Shopping malls were once found in Metro Manila, Metro Cebu and Metro Davao. Today, even first- to second-income class municipalities in Philippine provinces have hosted these malls and supermarkets. Interestingly, across regions, the number of middle-income class families is steadily increasing.

The discussion on the macro- and meso-level economic performance of the Philippines helps us contextualize the operations of community newspapers. For obvious reasons, buoyancy of local economies means good news for the community news media —with particular reference here to regions outside of Metro Manila. Looking at the membership of just one coalition or network of newspaper publishers, there are even more community newspapers that are members of the Philippine Press Institute (PPI) in the second poorest region —Eastern Visayas (the one struck by typhoon Haiyan, the world’s strongest weather system to hit landfall)— than in developed regions such as Calabarzon (Region 4a), Western Visayas (6), Central Visayas (7) and Davao (11). Levels of local economic growth in these poorer regions have not deterred publishers from publishing printed publications of all types — be they published by local entrepreneurs-cum-journalists, local government units, or even the Catholic Church. This reveals that levels of local economic growth are not a stumbling block to the establishment of community newspapers.

FILIPINO JOURNALISTIC CULTURE

In the absence of empirical research (especially quantitative data) on the journalistic culture of Filipinos, there is the view that Filipino journalists are “torn” — divided between being advocates (a product of the birth of the Filipino nation) and being “objective” journalists, given the implanting of journalism into the country by the Americans in the early 1900s (Teodoro, 2001). The early national newspapers of the Philippines during the American period (1898-1946) imbibed the Libertarian tradition of the U.S. press to the point that even “nationalistic” Philippine newspapers faced threats from American colonizers.

Since the Philippines became an independent country, Philippine journalism has flourished, with 1946 to 1972 being referred to as the “golden age of Philippine journalism” (Braid & Tuazon, 1999). It was also during this period, at least for national newspapers, that newspaper publishers had to collaborate with top businesspeople to sustain the operations of newspapers. But it was also during this period that Filipino journalists embraced watchdog roles. In fact, this watchdog role led to the killing, in May 1966, of a publisher of a community newspaper, Ermin Garcia, Sr. of The Sunday Punch (in Pangasinan province, north of Manila). At that time, there was also concern about improving Filipino journalism and upholding press freedom, leading to the formation of groups such as the National Press Club (NPC) in 1952, the old Federation of Provincial Press Clubs (FPPC) in 1963, and the Philippine Press Institute (PPI) in 1964 (Tuazon, n.d.). FPPC and PPI included community newspapers in their membership rosters, showing that the community press has been around for some time.

But the imposition of martial law by then-strongman President Ferdinand Marcos changed the complexion of Philippine journalism. Marcos was suppressing press freedom and closed newspapers said to be critical of his regime. The activism movement, amid real threats such as political detention, began to show itself during the 1970s. At around this time, DEPTHNews initiated its work on “development journalism,” but the stories did not include criticisms against government given Marcos’ attitudes toward media.

In the 1980s, Filipino journalists tried to go underground and set up newspapers that were regarded as the “mosquito press” by allies of Marcos. But when Senator Benigno Aquino, Jr., was assassinated at Manila’s international airport on Aug. 21, 1983, the Filipino nation was awakened — as were its journalists. Marcos was thrown out of power and Aquino’s wife, Corazon, became president and restored democratic institutions, including press freedom.

While a research on the history of the community press in the Philippines remains wanting, papers as early as Maslog’s in 1971 carried some information and findings that revealed a profile of community newspapers. The community press was described as the “forgotten sector” that is “weak and anemic” to fill information gaps that national media cannot (Maslog, 1971). While the FPPC and PPI were formed during the 1960s, at that time there was confusion as to the number of community newspapers. A communication school in central Philippines, Siliman University, conducted a survey of rural editors. Of 112 target respondents, a total of 52 community newspapers replied. That survey enabled Maslog and Siliman University to make an initial profile of the Filipino community newspaper and its editors:

- Typically, the community newspaper was a weekly tabloid in English. Owned by an editor, these newspapers were seen as “politically independent;”

- The average community newspaper editor was middle-aged, married, a Catholic, had a college degree, had not travelled abroad, occasionally worked in public relations or advertising for other people, was active in community work, and worked only part-time for the community newspaper; and

- The community newspaper earned “reasonable” profits, even as one out of ten newspapers admitted the newspaper “was losing money” or was “barely breaking even.”

Maslog concluded that the view that community newspapers’ potential for national development was great, but this sector “needs to be developed first” before such role can be fulfilled (Maslog, 1971).

This historical retracing of Philippine journalism finds relevance in showing, at least through historical accounts, the journalistic culture of Filipinos. Hanitzsch (2007) theorizes journalism culture as “a shared occupational ideology among newsworkers” — spanning the cultural diversity of journalistic values, practices and media products. Such discourse had been tested by Hanitzsch and collaborators in a two-round, multi-country study on journalism cultures (round 1 of study: 2007-2011 and round 2: 2012-2014). Among the concepts tested were four milieus of journalistic cultures:

- Populist disseminator, with a strong leaning toward the audience (of providing the audience with “interesting” information). These journalists do not intend to take on active and participatory roles in reporting;

- Detached watchdog, with an interest in providing political information to audiences. Here journalists have relatively high regard for their role as a “detached observer of events,” and they are least likely to advocate for social change, influence public opinion and set the political agenda.

- Critical change agent, which is driven by interventionist intentions. These journalists are critical toward government and business elites, and advocates for social change through agenda-setting measures; and

- Opportunist facilitator, in which journalists are constructive partners of the government. Here, journalists are most likely to support official policies and convey a positive image of political and business leadership.

As to be explained in succeeding portions of this paper, community journalism in the Philippines is a tale of two faces: the face of a critical change agent and the face of a business venture. Similar to the Metro Manila-based national newspapers, community journalism may be adopting a business model that encourages the role of the journalist as a critical change agent. These two faces of the community press operate in a milieu of press freedom (now guaranteed by the post-Marcos Philippine Constitution of 1987), in a period of changing habits of media usage by Filipino audiences, and in a current environment in which journalists’ safety and welfare are both under attack.

CURRENT STATUS OF THE PHILIPPINE COMMUNITY PRESS

Audience profile

Updating data on media consumption habits by Filipinos remains a challenge. For purposes of this paper, the authors cite data from the market research firm AC Nielsen that did the Nielsen Media Index. As of the 2010 Index, the reading of newspapers is third behind television watching and radio listening across the major island groupings. What is also interesting is that low incomes did not reduce for media consumption — especially for newspaper reading, particularly for the poverty-stricken Mindanao province. This can be a function of pass-on readership, as well as the purchasing of nationally and locally published tabloids whose prices are cheaper than the broadsheet. Especially for Mindanao, the rising numbers of the middle-class families may have spurred the use of media including newspapers and the Internet. This development augurs well for the community newspaper sector.

Growth of Philippine community newspapering

Nearly five decades since the Maslog surveys (1967, 1971), Philippine community newspapers have grown in terms of the number of publications that are circulating. Amid the Internet’s rise as a medium and the national reach of broadsheets and broadcast networks based in the National Capital Region, communities outside of Metro Manila still find the publication of community newspapers relevant. Community newspapers have turned out to be profitable ventures, apparently leading other publishers to open their own community newspapers.

Established community newspapers, such as The Sunday Punch (Pangasinan in Ilocos region) or The Bohol Chronicle (Bohol in Central Visayas region), persist to this day. There are also long-running chains of community newspapers, such as the SunStar Group, which started out in Cebu province and now publishes SunStar community newspapers in 11 provincial cities plus a news service in Metro Manila. There are also younger chains of community newspapers in Mindanao such as the Businessweek Mindanao group of newspapers. The reach of the newspaper copies for some community newspapers is expanding; the Mindanao Gold Star Daily now covers 24 provinces (including 20 cities) in Mindanao. Newer, independent community newspapers are also coming up. Metro Manila’s national newspapers have either bought majority shares of community newspapers (e.g. The Freeman of Cebu, which Philippine Star bought) or have set up community newspapers as part of the national media’s newspaper groups (e.g. Cebu Daily News of the Philippine Daily Inquirerand Daily Tribune Mindanao/Mindanao Insider of the hard-hitting Daily Tribune).

It is also worthy of note that the recent growth of the community newspaper industry, particularly in rural communities, seems to be driven by same factors that drove Filipino community newspaper success in the past: citizens’ need to know what is happening in local communities, educated readers in a country whose families value education, and participatory interest in the community, according to Rina Afable-Locsin, assistant professor of journalism at the University of the Philippines in Baguio City (personal communication, November 2014). This participatory interest from members of newspapers’ immediate communities, especially in communities with less-dense populations, continues to make community newspapers distinct from national news media. Social media have reinforced this community-level participatory interest. But in some communities, word-of-mouth still remains effective, according to Red Batario, executive director of the Center for Community Journalism and Development (CCJD) (personal communication, November 2014).

‘EVOLVING’ ROLES AND TRENDS IN PHILIPPINE COMMUNITY JOURNALISM

Change agents or opportunists? Hanitszch’s discourse on journalistic culture (2007) offers a guide for discussing the current dynamics of community journalism in the Philippines. A survey of community newspapers or community journalists does not enable us to see if Filipino community journalists are populist disseminators, detached watchdogs, critical change agents or opportunist facilitators. But, depending on the disposition of these Filipino community newspapers and community journalists, economic survival is tied to these.

The growth of community newspapering in the Philippines may be tied to there being critical change agents or opportunist facilitators. Some community newspapers are critical change agents in the sense that journalists — many of them with roots in rural communities — know what prevails locally and feel compelled to report these community-level developments (R. Batario, personal communication, November 2014). Some other community newspapers are opportunist-facilitators in the sense that these newspapers, given people’s relationships with each other, relate with the powers-that-be so as to collar not just political ties but possible revenues from local coffers. Popular sources of revenue of community newspapers are judicial notices from local trial courts, advertisements from local government units (e.g. announcing enacted ordinances, public bidding opportunities) and political advertising during triennial local elections (or even months earlier from those electoral exercises). So a Filipino community newspaper, on one hand, may have the motivation to publish stories that contain community concerns and find revenue streams along the way; on the other hand, a community newspaper publishes weekly editions to draw in advertising revenues to the point of not being wholly conscious of the “journalistic” standard that this newspaper is supposed adhere to (R. Batario, personal communication, November 2014).

Roles. The roles of these community newspapers and community journalists remain the same: as purveyors of community-related information; as instigators of discussions given stories (or kuwentong bayan, as this is referred to in some Philippine communities) affecting local citizens; and as monitors of community issues, sometimes in partnership with identified stakeholders like civil society organizations or cause-oriented citizens. These roles for community journalism in the Philippines reveal the evolution of the concepts, from development journalism in the 1970s (wherein the journalists report on local socio-economic issues that are underreported) to today’s civic journalism (wherein journalists, while maintaining their independence, report on issues and engage with audiences that allow citizens to discuss issues).

Community journalism in the Philippines is closely associated with civic journalism: It is connected to a specific geographic setting and embraces a reciprocal relationship between journalists and community members. From 1996 to 2007, the Philippine Press Institute (PPI) called its annual awards for outstanding community newspapers the “Community Press Awards.” Since 2008, PPI has called these awards the “Civic Journalism Awards” (Philippine Press Institute, 2014).

Veteran Manila-based journalist Vergel Santos (2007) calls civic journalism “the same journalism, only more localized.” Civic journalism as a concept also “supplements” the content of community journalism. Santos explains why the concepts community journalism and civic journalism suit each other:

It [civic journalism] suits journalism to community conditions in ways that national or cosmopolitan practice, since it is intended for much larger and more diverse audiences, does not. [Civic journalism] attacks local gut issues with such focus and thoroughness as it engages every sector of the locality. In other words, civic journalism turns the news media into a catalyst for community action, thus promising the community a distinct identity and sense of self-reliance. (Santos, 2007, p. 15)

Civic journalism’s introduction into the community press is an innovation Philippine journalism has produced. In many respects, the use of civic journalism techniques in community journalism is what the development journalism movement in the 1970s envisioned. On the part of the individual community journalist, since he or she is “homegrown,” executing roles is done “in a homegrown manner” — reporting from the lens of the journalists’ personal experiences and their own take on what the community needs (R. Afable, personal communication).

More than community engagement or facilitation, civic journalism stresses the production of credible news content, according to Ariel Sebellino, executive director of the Philippine Press Institute (PPI) (personal communication, November 2014). In an ideal setting, the community newspaper starts off the process of doing civic journalism by reporting initially on an issue. What follows are activities in which the journalists or community newspaper bring together stakeholders to discuss such issues. Afterwards, the views from these people that were mentioned in the newspaper-facilitated activities (e.g. dialogues) are sources in follow-up stories or special reports. If executed properly, these stories can deter the powers-that-be from making decisions that may be “detrimental” to local residents (R. Batario, personal communication, November 2014). In this respect, the community newspaper is ascribed a role in “societal transformation” (A. Sebellino, personal communication, November 2014) — that the newspaper can be “aggressive” in framing stories that challenge people to have a stake in local issues affecting them. Natural disasters are an example where a community newspaper’s stories challenge the community to take action.

Adoption of civic journalism techniques in community newspapers is, however, seen in a limited number of newspapers – primarily news publications that see the value of the concept of civic journalism after, for example, participating in a training activity on civic journalism. A visible majority of the community press in the Philippines are still motivated primarily by profit, which is not entirely bad in itself. But blending the market orientation with community journalists’ capabilities and understanding of how journalism is supposed to operate — from reporting to publishing, and carrying the trait of independence from factions — remains a challenge. Even a casual observer can easily see which newspapers publish credible content. But other newspapers whose personnel may lack the training in journalism still find a visible place in local communities, and they may thrive as business ventures.

TRENDS IN THE PHILIPPINES MEDIA LANDSCAPE

There are other developments that can be seen from the community newspaper sector in the Philippines:

- Elaborate staff compositions in the community press. Staffing in community newspapers was initially a family affair or was made up of a few dedicated personnel who took on editorial, administrative and marketing roles. While there are still community newspapers with limited staffing, there is now the realization of expanding personnel as investments for the aspired profitability of the community newspapers. This trend (see Table 1) can be seen in a cursory look at this year’s staff boxes of nearly a hundred community newspapers. The development may be a reflection of the evolution of the community newspaper as a business venture, recognizing the ingredients necessary in the value chain of a newspaper.

- The competitive nature of the community newspaper sector depends on the dynamics of local communities. In areas such as Metro Cebu (in Cebu province, central Philippines), Baguio City (in Benguet province, north of Manila), Cagayan de Oro City (in Misamis Oriental province in Mindanao) and Davao City (an independent city also found in Mindanao) community journalism thrives given residents’ thirst for community-level information, perhaps encouraging more aspiring publishers to try out this business. But this is not the case in other local communities, even those with visibly buoyant local resources. This may have to do with differing media or news preferences by local audiences. What should also be considered is that compared to Metro Manila, the target markets of community newspapers remain small; as an example, a scant few provincial communities in the Philippines have community publications that already have specialized publications such as lifestyle magazines and community-level business newspapers. Some areas have tried to emulate the vibrant situations seen in other Philippine provincial communities, but local audiences may not be responding to such moves by community newspapers (R. Batario, personal communication, November 2014).

- Within community newspapers, division still prevails. The disposition of the community newspaper publishers toward journalism — from the basic knowledge of how journalism is done to the role of the community newspaper in local communities — is a starting point of the community newspaper sector’s division. Community newspapers that are critical change agents are one group while others that are considered either as detached watchdogs or opportunist facilitators are another group. One network of newspaper publishers admits to being selective in inviting community newspapers to be members since the network focuses on the “quality” of the newspapers’ journalism.

There are also many other community newspapers that are either members of a newspaper publishers’ network, the Publishers Association of the Philippines Inc. (PAPI), or are not members of any of existing national coalitions of newspaper publishers. In some local communities, regardless of affiliation or disposition in terms of journalism culture, camaraderie among journalists prevails in local-level press clubs for the simple reason that members are kindred souls: journalists. Another factor that has probably united differing groups of community newspapers, at least in principle, is the slaying of community journalists, to be explained in more detail below. - The Internet is threatening economically challenged community newspapers. This observation especially goes out to rural areas with limited Internet connectivity and less-developed telecommunications infrastructure, as well as to community newspapers with limited financial resources to set up a news website and have personnel regularly uploading and circulating content worldwide. In general, the use of the Internet and social media by community newspapers remains behind when compared to the national newspapers in Metro Manila.

Only a few moneyed community newspapers, such as the SunStar Group, have opened dedicated news website services that disseminate news from the published newspaper editions and breaking news, and that share stories through social media platforms. The majority of community newspaper stories online, based on a perusal of the community newspapers and the newspapers’ available news sites, appear to come from stories in their newspaper print editions. For others with no resources to open a regularly maintained news website, some community newspapers bring to Facebook their stories and the PDF files of their weekly newspaper editions. Sensing that community-centered news via the Internet remains lacking, some independent news producers open up Internet news websites such as MindaNews, Mindanao Examiner and Northern Dispatch (NORDIS) — to which their stories are being syndicated (with associated fees) to the community press. It also seems that younger, educated audiences may have driven community news organizations and newspapers to go online and be visible in social media (R. Batario, personal communication, November 2014). - A profitable community press? Community newspapers envy the national newspapers that receive the attention of big-ticket advertisers. In the past, a Manila-based intermediary accounts group received advertisers from Metro Manila on behalf of community newspapers, and the intermediary got a share from advertising intake.

Community-level advertising persists as the main source of advertising revenue for the community press. But the amount of revenues then depends on the level of economic growth in local communities, the presence of local enterprises and the aggressiveness of community newspapers’ advertising and marketing personnel to reach a part of the market. National-level data show that a big number of enterprises are micro-enterprises and these mostly thrive in rural areas.

Local community advertising intake differs, again being a function of local audiences and local economic dynamics. The leading regions for Philippine community journalism are fortunate in these respects. In other communities, community newspapers rely on their standing in the community or their longevity such that local residents know these papers to be trustworthy and independent (R. Reyes, personal communication, October 2014).

Given differing situations surrounding advertising intake by community newspapers, few are expanding and many are subsisting, even on a daily basis — a trend that had been seen decades ago (R. Batario, personal communication, November 2014; A. Sebellino, personal communications, November 2014). The Internet as the next source of revenue for the community press remains in its infancy, though community newspapers are banking on the community connection, especially given community members based abroad who reconnect with their rural birthplaces. Publication of judicial notices remain as an easy revenue earner for the community newspaper. Community newspaper publishers are also owners of printing presses (R. Locsin, personal communication, November 2014), lowering the cost of publishing a community newspaper. The printing press helps lessen the high risk of maintaining a community newspaper. - Old issues persist. Economic conditions of community newspapers still lead to the continued presence of other issues affecting journalism: media corruption, journalists’ co-optation with sources (Tuazon, 2013; Chua, 2013), observations of “lower quality” reportage, media bribery, and limited human and financial resources to conduct enterprise reporting.

Inasmuch as some of these community newspapers want to become independent, community newspapers try to balance their desire to be independent with their attachment to the community. In small communities audiences can easily determine whether a community newspaper has lost its credibility or not. The community newspaper also understands that the community connection is hard to dissociate, this being the business model of community newspapers (R. Reyes, personal communication, November 2014). As such, citizens’ perception of community journalists still carries a huge bearing, with these journalists still being “part and parcel” of the community (R. Batario, personal communication, November 2014). - The impunity that threatens community journalists. Media killings are easily the single biggest threat to Filipino journalists. This was made evident in the massacre of 32 community print and broadcast journalists (part of a total 58 people killed) by a powerful local political clan (the Ampatuan), in Salman village, Ampatuan municipality in Maguindanao province, Mindanao on November 23, 2009 (Quinsayas, 2012). The slaying of community journalists is not a new phenomenon; Maslog (2013) noted the “early martyrs of Philippine journalism” such as Cebu community journalist Antonio Abad Tormis of the defunct daily paper Republic News, killed in 1961; Ermin Garcia, Sr. of The Sunday Punch in Pangasinan province in 1966; and Jacobo Amatong of The Mindanao Observer in Dipolog City, Zamboanga del Norte province, in 1984.

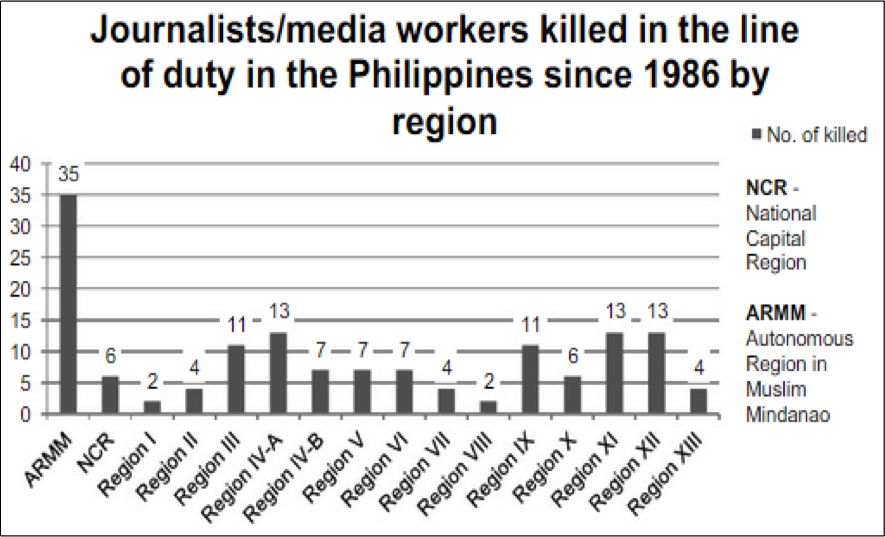

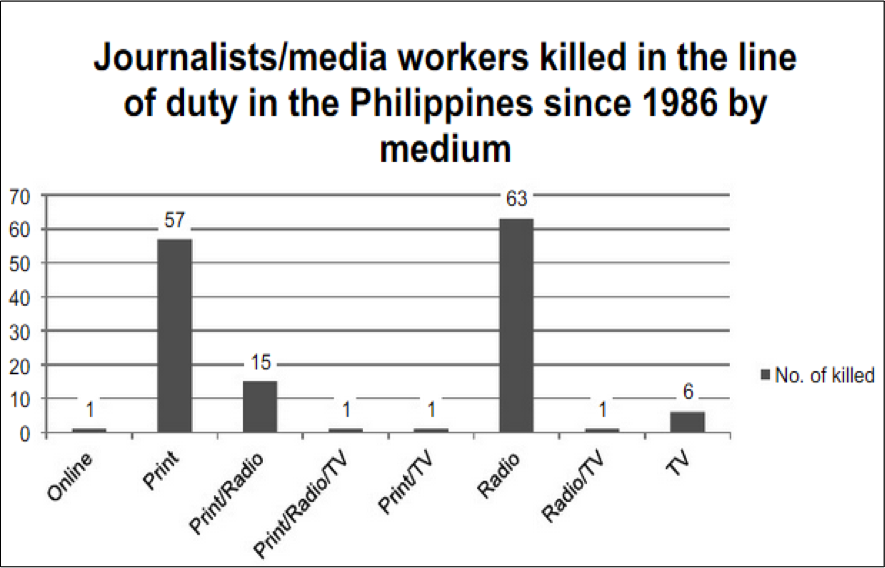

This culture of impunity made the Philippines one of three countries in the world that had become the most dangerous for journalists (Reuters, 2014). The Philippine situation is unusual in that it is a democracy, and the media killings have not been associated with war or civil conflict. As of this writing, 217 Filipino journalists have been killed since 1986, with 145 of them killed in the line of duty (See tables 2 and 3). Under the current regime of reformist President Benigno Simeon Aquino III, which began July 1, 2010, 25 journalists have been slain (Center for Media Freedom and Responsibility, 2014). Radio journalists, with radio being their primary and solitary media affiliation, are the most killed, followed by print journalists. In all provincial regions of the country there are recorded murders of journalists, especially in developed regions (Central Luzon [Region 3], Calabarzon [4a] and Davao [11]) as well as in the region where the Maguindanao massacre happened, the Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (see Figure 1). Some do hope that if local communities are conscious of the role of journalism in a democracy in these immediate provincial communities, the people themselves will help protect the journalists (R. Batario, personal communication, November 2014).

Continued challenges facing the community press

Obviously, the killing of journalists is Philippine journalism’s single greatest challenge. But many of the challenges facing community journalism are decades old. Many community journalists remain less equipped, especially since journalism is not their primary academic training. Media corruption persists even with the culture of media impunity as the backdrop.

There may also be issues, though not admitted to in public or through research papers, in the way that community journalists manage the entrepreneurial side of their work. While publishers with strong business acumen do not find problems managing these newspapers, journalists who are not trained entrepreneurs juggle both editorial and entrepreneurial responsibilities, perhaps making community journalists more open to employ unethical media practices.

CONCLUSION

Community journalism in the Philippines remains glued to the geographic reference of the concept (Maslog, 2012). As shown in this paper, a Southeast Asian archipelago’s geographic dispersion is a natural setting for community newspapers to thrive and for communities to continually prefer reading local news. Metro Manila media remain an influential segment of overall Philippine journalism, but journalism may provide a way to link national and community newspapers: News, especially when well contextualized, connects Filipinos in general (R. Batario, personal communication, November 2014). This connection occurs not just when tragedy strikes in local communities, and operationalizing this connection between Manila (too national) and the provincial communities (too local) may require a rethinking of community journalists’ editorial approaches to stories. Then again, the economic viability of this editorial approach to community journalism is yet to be seen.

Nevertheless, and amid the prevailing weaknesses and challenges confronting community newspapers, Philippine community journalism is currently enjoying a window of opportunities from not just the Internet, but also from visibly felt local economic growth and the gradual rising of the middle-class in provincial communities. These economic opportunities offer an opportune time for civic journalism, if practiced by community newspapers, to reconnect journalists with their communities. These provincial communities may continually resort to old ways in using media and in consuming news, as community newspapers then embrace new ways of producing and disseminating news. But one may wonder if there already prevails a disconnection between the community newspaper and the community and its members. A ramification of this development, even with today’s penchant for civic journalism, is that audiences may not understand the community newspapers’ stories, or do not care about these stories (R. Batario, personal communication, November 2014).

Connectedness with people in local communities remains the editorial and business model of community journalism in the Philippines. Filipino community newspapering is also slowly becoming more professionalized not just in terms of the stories being written, but also in the editorial and business expansion measures these papers take on. The role of Filipino community journalism has evolved, especially for newspapers that are serious in showcasing journalism’s important role in democracy. There are threats that come from within these newspapers and from the prevailing geographic environment, yet these underpaid journalists and their under-resourced community newspapers have been taking on the challenge to continually find viable economic formulas fed by the conduct of credible, independent journalism.

Not surprisingly, the Philippine case presents many possible areas for future research on community journalism. These can cover culture’s and local identity’s role in community journalism; managerial aspects of newspaper publishing; the psychology of community journalists’ behavior in dealing with news sources who are from the community; and ethics in community journalism. If the community press in the country espouses the tenets of “civic journalism,” do their stories reveal such?

But what can international community journalism learn from the Philippines? On the editorial side, analysis of international community journalism can probe deeper into the attempts of these stories to connect journalists with communities (especially if there are efforts to include a multitude of community voices, not just the usual suspects such as local officials and local experts). In terms of journalistic culture, how does being a critical change agent or an opportunist-facilitator impact business operations? Local politics vis-à-vis journalism is another dynamic for further analysis. While development journalism as a concept in the 1970s had evolved into current-day civic journalism, community journalism by Filipinos may continue to have a role in local development.

Maslog (1971) said that the community press provides alternative information to Filipinos that the national news media cannot provide, especially since national news media cannot report happenings in local communities. Could the current socio-economic situation of the Philippines help community journalism realize the potential that Maslog (1971) envisioned? The old habits, or beliefs, of Philippine community journalism prevail. But new approaches to community journalism may help Filipino journalists to become, or remain, relevant locally.

WORKS CITED

- Braid, F. & Tuazon, R. (1999). Communication media in the Philippines: 1521-1986. Philippine Studies, 47, 291-318.

- Center for Media Freedom and Responsibility (2014). Data on Filipino journalists killed. Retrieved from http://www.cmfr-phil.org/flagship-programs/freedom-watch/research-and-an….

- Chalkley, A. (1968). A manual of development journalism. Manila, Philippines: Thomson Foundation and the Press Foundation of Asia.

- Chua, Y. (2013). Ethics and community press. Commissioned research for the Philippine Press Institute (PPI).

- Hanitzsch, T.(2007). Deconstructing journalism culture: Towards a universal theory. Communication Theory, 17, 367-385.

- Hatcher, J.(2012). Community journalism as an international phenomenon. In B. Reader and J. Hatcher (Eds.). Foundations of community journalism (pp. 241-254). United States of America: SAGE Publication.

- Hatcher, J. & Reader, B. (2012). New terrain for research in community journalism. Community Journalism, 1(1), 1-10.

- Institute for Migration and Development Issues (2008). The first Philippine migration and development statistical almanac. Manila, Philippines: Author.

- Maslog, C. (1971). The Philippines mass media. Presented at a Traveling Seminar (organized by the Asian Media Information and Communication Centre), Singapore: September.

- Maslog, C. (1985). Five successful asian community newspapers. Singapore: Asian Media Information and Communication Centre.

- Maslog, C. (1989). The dragon slayers of the countryside. Manila, Philippines: Philippine Press Institute.

- Maslog, C. (1993). The rise andfFall of Philippine community newspapers. Manila, Philippines: Philippine Press Institute.

- Maslog, C. (2012a). Asian and American perspectives on community journalism. In B. Reader and J. Hatcher (editors). Foundations of Community Journalism (pp. 125-128). United States of America: SAGE Publications.

- Maslog, C. (2012b). Prologue: early martyrs of Philippine journalism. In F. Rosario-Braid, R. Tuazon and C.Maslog (Eds.). Crimes and unpunishment: The killing of Filipino journalists (pp. 111-128). Manila, Philippines: Asian Institute of Journalism and Communication (AIJC).

- McKay, F. (1993). Development journalism and DEPTHNews. International Communication Gazette, 51, 237-251.

- Mejorada, M. (1990). The community press in the Philippines. Presented at the CAF-AMIC Workshop on the Rural Press (organized by the Asian Media Information and Communication Centre), Singapore: June.

- phd Media Network (2013). phd Media Factbook 2013. Manila, Philippines: Authors.

- Philippine Press Institute (2014). PPI @ 50 and beyond. Souvenir program for the 18th National Press Forum and 2014 Annual Membership Meeting, Manila, May.

- Philippine Statistical Authority (2014). Regional economic structure 2013. Retrieved from http://www.nscb.gov.ph/grdp/2013/visualizations/RegionalEconomyStructure….

- Quinsayas, P. (2012). The Ampatuan, Maguindanao massacre of 32 journalists: Crime of the Century. In F. Rosario-Braid, R. Tuazon and C. Maslog (Eds.). Crimes and unpunishment: The Killing of Filipino Journalists (pp. 138-155). Manila, Philippines: Asian Institute of Journalism and Communication (AIJC).

- Reuters (2014, February). India among five most dangerous countries for journalists in 2013. Reuters. Retrieved from http://in.reuters.com/article/2014/02/18/india-media-journalists-deaths-….

- Santos, Vergel (2007). Civic journalism: A handbook for community practice. Manila, Philippines: Philippine Press Institute.

- Schuman, Michael (2014, March). Forget the BRICs; Meet the PINEs. Retrieved from http://time.com/22779/forget-the-brics-meet-the-pines/.

- Tuazon, R. (no date). The print media: A tradition of freedom. Retrieved from www.ncca.gov.ph/about-culture-and-arts/articles-on-c-n-a/article.php?igm=3&i=221.

- Tuazon, R. (2013). In honor of the news: Media reexamination of the news in a democracy. Manila, Philippines: UNESCO National Commission of the Philippines.

- Virola, R., Encarnacion, J.O., Balamban, B.B., Addawe, M.B. & Viernes, M.M. (2013). Will the recent robust economic growth create a burgeoning middle class in the Philippines? Presented at the 12th Philippine National Convention on Statistics, Manila, October.

- Virola, R., Astrologo, C. & Rivera, P. A. (2010). Disturbing statistics: The Philippines compared to our ASEAN neighbors. Presented at the 11th Philippine National Convention on Statistics, Manila, October.

- World Bank-Philippines (2014). Philippine economic update: Pursuing inclusive growth through sustainable reconstruction and job creation. Report no. 83315-PH. Manila: World Bank-Philippines Poverty Reduction and Economic Management Unit.

- Xiaoge, X. (2009). Development journalism. In K. Wahl-Jorgensen and T. Hanitzsch (Eds.). The Handbook of Journalism Studies (pp. 346-370). United States of America: SAGE Publications.

APPENDIX

TABLE 1: COMMUNITY NEWSPAPERS AND THEIR NUMBER OF PERSONNEL

| Role/s and position/s in the community newspaper | No. of community newspapers | ||

| One-to-two staff | Three-to-five staff | Six staff members and above | |

| Publisher and editorial board members | 27 | 19 | 4 |

| Section editors | 5 | 1 | 1 |

| Reporters, correspondents and photographers | 5 | 7 | 16 |

| Marketing, advertising and administration* | 28 | 6 | 2 |

| Technology | 8 | — | 1 |

| Legal | 13 | — | — |

*This classification includes financial managers, circulation personnel and business managers.

TABLE 2.

TABLE 3.

About the Authors

Jeremaiah Opiniano is an assistant professor and coordinator of the journalism program of the University of Santo Tomas (UST), Southeast Asia’s oldest journalism school.

Jasper Emmanuel Arcalas is a third-year journalism student at the University of Santo Tomas.

Mia Rosienna Mallari is a third-year journalism student at the University of Santo Tomas.

Jhoana Paula Tuazon is a third-year journalism student at the University of Santo Tomas.