Leigh Landini Wright

Journalists long have been the gatekeepers of content for traditional media, but now with social media, does that role still stand? Although studies have focused on larger circulation newspapers, the literature suggests a gap among community newspapers’ judgment of news values and gatekeeping as applied to social media postings. A survey of 108 journalists working at newspapers with a circulation of 30,000 or less revealed insights into how journalists perceive the traditional news values when posting to the social media. Helpfulness played highly on Facebook while timeliness played better on Twitter.

In today’s society, news and social media seem intertwined. People merely need to pick up their phones and scroll through Facebook or Twitter to catch up on headlines from the world or as close as their neighborhood. The Pew Research Center began tracking Americans’ interactions with social media in 2005 and found only 7 percent of people used social media, but by 2015, that number had soared to 65 percent of adults (Perrin, 2015). As Americans continued to log in to sites such as Facebook and Twitter to connect with friends and family, news organizations began using these social networking sites to connect with their readers. In 2013, 47 percent of Facebook users said they found news on that social networking site (Mitchell, Kiley, Gottfried & Guskin, 2013). By 2015, 63 percent of Facebook and Twitter users said they used these social networking platforms to access news about events and issues outside their sphere of friends and family. This statistic increased from 52 percent on Twitter and 47 percent on Facebook just two years earlier (Barthel, Shearer, Gottfried & Mitchell, 2015). Furthermore, 59 percent said they kept up with Twitter during a live news event while 31 percent kept up on Facebook (Barthel, Shearer, Gottfried & Mitchell, 2015).

Additionally, one in 10 Americans consume news on Twitter and four in 10 on Facebook, and the Pew researchers found an overlap of 8 percent between those who use both Facebook and Twitter to consume news (Barthel, Shearer, Gottfried & Mitchell, 2015).

In Pew’s 2013 study, a third of Facebook users who followed news organizations said they connected with an individual journalist to follow updates, and these news consumers were more likely to click on news links to discuss issues with their friends (Mitchell, Kiley, Gottfried & Guskin, 2013). As social media gained a stronghold as the go-to source for Americans to communicate with friends and keep up with their communities, journalists and news organizations began to see the value of a social media presence on platforms such as Twitter and Facebook.

The Washington Post, for instance, mandated in mid-2011 that reporters use Twitter and Facebook (Rosenberry, 2013). Researchers at the University of Missouri found that 84 percent of daily newspapers use Twitter or Facebook (Rosenberry, 2013). Greer & Yan (2010) used a content analysis of newspapers with a circulation of under 50,000 over a 10-month period in 2009-2010 and found steady growth in social media usage, including a doubling of Twitter use within that time (Greer & Yan, 2010).

However, the literature yields little about the usage and trends of social media at newspapers with circulations of 30,000 or less. This pilot study chose the 30,000 or less threshold for circulation as a benchmark for smaller newspapers that may not be studied as frequently as larger metros. This study seeks to find the motivating factors for journalists setting the news determinants and the relationship between those news determinants or news values when posting to social media at daily newspapers with a circulation of 30,000 or less.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Theoretical Framework: Gatekeeping

Psychologist Kurt Lewin (1947) first devised a theory that tracked the flow of the channels by which food reaches the dinner table and determined that a specific area could function as the gate as a part passed through a whole. Although the original case applied to food, the gate later applied to news items, and gatekeepers ruled the gate sections and controlled the flow of information (Lewin, 1947). David Manning White applied gatekeeping to journalism in the 1950s and studied why newspaper wire editors selected stories for publication. White (1950) used a wire editor, defined for his study as a white man in his 40s at a newspaper with a circulation of 30,000 in an industrial Midwestern city, as the gatekeeper who controlled the flow of information from the wire services to the newspaper audience. White queried the editor about the reasons behind his choice of wire news copy and found the editor made his decision based on personal experiences (White, 1950). Snider (1967) replicated White’s study with the same editor, dubbed Mr. Gates, and found the story selections were still based on Gates’ perceptions and news could be defined as “the day-by-day report of events and personalities and comes in variety which should be presented as much as possible in variety for a balanced diet” (Snider, 1967, pg. 426). Bass (1969) studied the role of the news gatherers (writers, reporters, local editors) in stage one and the news processors (editors, copyreaders and translators) in stage two, concluding that the person’s role within the organization defined his perception (Bass, 1969). Halloran, Elliott, and Murdock found that gatekeeping began with the reporter and the gatekeeping function among the editorial staff varied from newspaper to newspaper (1970). However, Chibnall (1977) wrote, “The reporter does not go out gathering news, picking up stories as if they were fallen apples. He creates news stories by selecting fragments of information from the mass of raw data he receives and organizing them in a conventional journalistic format” (1977, p. 6).

Studies (Gieber, 1956, Westley & MacLean, 1957) concluded that gatekeeping was not as much a personal decision as it was an organizational one. Herbert Gans (1979) found that gatekeeping is more of a process than an individual decision, as information is packed for an audience. Gans asserts that “the news is not simply a compliant supporter of elites or the Establishment or the ruling class; rather, it views nation and society through its own set of values and with its own conception of the good social order” (1979, p. 62). Shoemaker, Eichholz, Kim & Wrigley (2001), who surveyed editors and reporters about stories resulting from fifty Congressional bills, found that routine forces, or those set by the news organization, were more significant than individual forces (Shoemaker et al., 2001).

However, when considering individual forces, one has to account for the demographics, ethnicity, gender, education, class, religion, and sexual orientation of the gatekeeper (B.C. Cohen, 1963; Johnstone, Slawski, & Bowman, 1976; Weaver, Beam, Brownlee, Voakes & Wilhoit, 2007; Weaver & Wilhoit, 1986, 1996). Weaver & Wilhoit (1996) examined the background of journalists and concluded that the average journalist in the 1990s was a white man earning $31,000 a year who had worked in the field for 12 years and worked for a medium-sized, group-owned newspaper (Weaver & Wilhoit, 1996). Their study (2007) more than 10 years later found no variation.

In the digital era, who is responsible for determining the content: the individuals or the organizations? Cassidy (2006) found little difference between the gatekeeping functions of legacy media and new media (Cassidy, 2006), and Singer (1997, 2005) suggested that print-based routines are still prevalent in the online news world. Cassidy (2007) also found that traditional print journalists question the credibility of online information and cited works from researchers Boczkowski, 2004; Deuze, 2005; and Singer, 2006, to suggest conflict exists between the traditional role of journalists as gatekeepers and the online world as a free publishing arena (Cassidy, 2007).

As newspapers continued to move into the online realm, Bruns (2003) suggested a model of “gatewatching” for online news rather than the traditional model of gatekeeping. Bruns (2003) said gate watchers watch the gates and then show their readers which gates will open to “useful sources.” The gatewatcher model also allows for a quicker posting of news and information since it is online, and newsgathering becomes “more transparent.” (Bruns, 2003, pg. 35).

Shoemaker & Vos (2009) challenged contemporary scholars to study gatekeeping in the 21stcentury, and they suggest asking questions about how communications routines differ among various forms of media and the assorted platforms.

News Determinants

What determines news? Editors and reporters long have relied on the gatekeeping theory to determine the flow of information between the news professionals and the audience. The classic study of news values (Galtung & Ruge, 1965) found that events that did not carry multiple meanings were more likely to be published. They identified 12 factors that they identified as important to news selection, which included frequency, continuity, elite people, and reference to persons (Galtung et al, 1965). A variety of definitions and determinants exist in the literature, but for the purpose of this study, the researcher chose to use Rich’s (2009) list that includes timeliness, proximity, prominence, unusual nature, conflict, impact and entertainment/celebrity (Rich, 2009). A reporter or editor generally decides on the newsworthiness of a story based on these criteria (Rich, 2009):

- Timeliness – Events are reported as soon as they happen or as soon as they are scheduled to happen.

- Proximity – Local readers care about what happens in their local communities.

- Prominence – Well-known people in the community become subjects of news articles.

- Impact – Newspapers seek local angles to world events and show their impact on the local community.

- Conflict – Stories report on conflict within a community.

- Helpfulness – Consumer, health and other how-to stories that provide information of use to the community.

- Entertainment/celebrity – Stories about entertainers or celebrities.

In a study of Swedish journalists and their news determinants, Stromback, Karlsson & Hopmann (2012) argued that the concepts of news selection, news values, news, and standards of newsworthiness should not be treated as interchangeable concepts as they are “conceptually and empirically distinct” (Stromback, Karlson & Hopmann, 2012, p. 725). Furthermore, they concluded using normative theory that no differences exist between the news values for traditional media and online media (Stromback et al., 2012).

Sheffer & Schultz (2009) studied whether blogs changed news values for newspaper reporters. Their study, a conceptual analysis, examined newspapers in three divisions (under 25,000 circulation, 25,000 to 100,000 circulation and 100,000-plus circulation) and found that journalists viewed blogs as another platform for traditional reporting. Sixty-three percent of newspaper bloggers examined did not include first-person writing, nor did the majority (87 percent) engage readers in a conversation (Sheffer & Schultz, 2009).

Media Trends

The proliferation of social media tools may have changed the dissemination and gathering of news for legacy media, but reporters still report on news and issues in their communities. Reporters now attend city and county government meetings, trials and even ball games with their smart phones or tablets tucked alongside their reporter’s notebook and recorder.

Social media tools allow reporters to report in real time and push content to their fans or followers. Grant (2012) proposed the seven functions for social media in journalism: report, promote, share, engage, follow, sourcing, and defend. Within these, reporting and sourcing allow journalists to use the news values of timeliness and proximity. “In the process, we need to reconceptualize our roles as journalists — instead of our being the source of information, social media allows us to become the hub for information” (Grant, 2012).

Journalists use Twitter to report events in real-time whether they cover a high-profile trial or a breaking news event. By using Twitter as a reporting tool, the reporters emphasize the news values of timeliness and proximity. National Public Radio reporter Andy Carvin used Twitter to tell the story of the Arab Spring uprising in the early months of 2011. He collected reports from the streets and tweeted up to a thousand times a day (Shephard, 2013). Carvin said he used multiple tweets to provide context for his readers and was careful not to repeat rumors. “That’s why it’s not unusual for me to tweet hundreds of times during a breaking news story because I’m constantly asking questions and reminding people what we know and what we don’t know” (Shephard, 2013). Mark Stencel, NPR’s managing editor for digital news, said Carvin actually turned the traditional reporting method public. “In a lot of ways, this is traditional journalism,” Stencel said. “He’s reporting in real time and you can see him do it. You can watch him work his sources and tell people what he’s following up on” (Briggs, 2013, pg. 96).

When Hurricane Sandy hit the East Coast in October 2012, reporters and citizens engaged in exchanging information via Twitter. According to the Pew New Media Index, 34 percent of the tweets produced during the storm involved news organizations, government sources, and the public reporting on news and human interest, yet another longtime news value. (Pew, 2012).

Besides tweeting 140-character updates of news unfolding in real time, Twitter also allows reporters to link to their sources or other news outlets, thus providing transparency in the reporting process. Lasorsa, Lewis & Holton (2011) found that 42 percent of the tweets from journalists from September 2009 to March 2010 contained an external link. (Lasorsa, Lewis & Holton, 2012, p. 24) Half of the tweets referred the public back to the news organization’s site, 25 percent to other media sites, 18 percent to external web pages and 7.2 percent to blogs. The researchers surmise that “some amount of accountability and transparency may be occurring in the microblogging activities of journalists” as reporting in real-time allows the journalist to show the audience their reporting and sourcing process (Lasorsa, Lewis & Holton, 2012, p. 24)

Those who apply gatekeeping theory to online media point to the use of a hyperlink as the act of enforcing the gate (Dimitrova, Connolly-Ahern, & Williams, 2003). De Maeyer (2012) asked journalism educators and journalists in Belgium about their views on hyperlinking and found they agreed that “classic journalistic principles are what should guide journalists’ linking behaviour” (De Mayer, 2012, pg. 699). Furthermore, Meraz (2009) studied political blogs in regards to hyperlinking and found the traditional mass media ruled the hyperlinking choices by linking to traditional news sources rather than citizen blogs or others (Meraz, 2009, pg. 702).

In social media, a widely accepted practice among both journalists and the public involves using hyperlinks within Facebook status updates or tweets to drive the reader back to a site, whether it’s a news site or another site. Hermida (2010) said when links are shared via Twitter, they create “a diverse and eclectic mix of news and information, as well as an awareness of what others in a user’s network are reading and consider important” (Hermida, 2010, pg. 303).

Bastos (2014) found in his study of social media postings by the staff at The Guardian and at The New York Times that Twitter is more useful for hard news items while Facebook is a stronghold for softer news such as fashion or entertainment. “As readership agency begins to deliver critical feedback to news items and interfere in the agenda of legacy media, newsrooms will have to strike a balance between news that editors understand to be important and news that answers the wishes of increasingly interactive and demanding readers” (Bastos, 2014, p. 17).

While much of the literature discusses social media postings at larger publications such as The New York Times or The Guardian, little has been written about the smaller publications typically associated with community journalism. Before discussing social media usage among community newspapers, one must define community journalism. Lauterer (2006) offered two definitions – one pertaining to circulation size and the other pertaining to the scope of what constitutes a community. Within circulation, Lauterer defines a community newspaper as one “with a circulation under 50,000, serving people who live together in a distinct geographical space with a clear local-first emphasis on news, features, sports, and advertising” (Lauterer, 2006, p. 1). However, community journalism also could extend to look at the broader segments of ethnicity, ideas, faith or interests (Lauterer, 2006).

Hatcher & Reader (2012) wrote about the need for scholarship to cover community journalism and determined that “community is no longer defined exclusively in terms of proximity or social homogeneity” and journalism is no longer limited to the work of reporters. “Today, a person can belong to a vibrant and active community without even knowing the people next door. Those communities still need and share news, opinions and other bits of information that fall under the big tent of journalism” (Hatcher & Reader, 2012).

However, community newspapers may be slower to adapt to the changing landscape of using social media in the reporting and dissemination process. One community newspaper editor in Eastern Kentucky wrote in Givens’ survey (2012) that Facebook could be viewed as a negative because it took the social news contributions (weddings, engagements, birth announcements, etc.) out of the community paper. The editor said all a person has to do now is log into Facebook and see pictures of a child’s birthday or special event that otherwise might have been submitted to the newspaper (Givens, 2012).

This study provides a snapshot of current media practices with regard to news value judgments against a theoretical framework of gatekeeping. Reporters and editors at daily newspapers with a circulation of under 30,000, which would fall into the smaller quarter of what’s defined as “community journalism,” were surveyed about their current practices of determining which news values matter when posting stories and/or links to social media.

RESEARCH QUESTIONS

Based on previous studies involving the individual and organizational forces of enforcing the gate and determining news content for audiences, the literature suggests the following questions for this study:

RQ1: Which news values influence a community journalist’s decision to post news content to social media platforms?

RQ2: What is the relative importance in a community journalist’s decision-making process for posting news content on social media platforms?

RQ3: Does a community journalist’s age and level of experience influence his or her decision to post news content to social media platforms?

RQ4: Does the publication, with a circulation of 30,000 or less, require journalists to abide by a written policy for posting content on social media sites?

METHODS

This study uses quantitative and qualitative methods to gauge the perceptions of journalists working for newspapers with circulations of 30,000 or less. The university’s Institutional Review Board approved all collection instruments and methods.

The researcher emailed 1,000 invitations containing a SurveyMonkey link to randomly selected journalists (reporters and editors) from 658 newspapers with circulations of 30,000 or less. The researcher gleaned email addresses from newspaper websites; however, 30 responses bounced immediately because the journalist to whom the email was addressed no longer worked for that publication, had exceeded his or her email mailbox storage limit or the spam filter rejected the unknown recipient. One hundred eight journalists responded to the survey, for a response rate of 11.4 percent. No benchmark figure for an acceptable response rate exists, but a postal survey sent without any other notification typically garners a low response rate of less than 10 percent (Descombe, 2014) and when Web resources are used, such as an electronic survey sent via email, the response rate can be comparable to a survey delivered via the postal service (Kaplowitz, Hadlock & Levine, 2004). Thus, the response rate, which included reminders, can be considered as representative for this pilot study.

Of those, 99.1 percent, or 107 respondents, indicated that their publication maintained social media accounts for news purposes, and only 0.9 percent, or one respondent, said the newspaper did not use social media.

Study Design

The survey included both qualitative and quantitative questions regarding journalists’ use of social media. The first section asked about the frequency of posting and their perceptions of the traditional news values on social media posting. The second section included open-ended responses about which news values they placed relevance on for social media posting and how they decided to pursue a story via traditional reporting means contrasted with how they decide to post information to social media. Two questions concerned whether administrators (editors, publishers, etc.,) had to approve social media postings and if the paper followed a written policy regarding social media.

The researcher emailed invitations with links to the SurveyMonkey instrument and then sent two reminder emails, each spaced two weeks apart, during the month of September 2013. Reminder emails typically have a positive response rate for Web surveys as compared with an email containing the survey (Kaplowitz, Hadlock & Levine, 2004). The data then was analyzed using SPSS, and the researcher chose to use t-tests and ANOVA.

FINDINGS

Demographics: Seventy-eight of the 108 respondents answered the demographics section. The respondents were evenly split (50 percent) on gender. With regard to age, 34.6 percent were ages 21-30, 16.7 percent were ages 31-40, 21.8 percent were ages 41-50, 20.5 percent were ages 51-60 and 6.4 percent for ages 61 and up. For experience, 34.6 indicated that they had 21 or more years in the business, followed by 24.4 percent for 0-5 years, 16.7 percent for 6-10 years, 6.4 percent for 11-15 years and 17.9 percent for 16-20 years.

The majority of respondents, 87.3 percent, held a college degree, 10.1 percent had a master’s degree and 2.5 percent listed their highest level of education as a professional or academic degree (J.D., M.D., Ed.D., etc.).

Seventy-nine respondents answered the question about their level of training in social media. Nearly 61 percent said they have learned on their own, 25.3 percent attended a seminar or webinar, 12.7 percent said they learned in other manners and 1.3 percent had no training.

Research questions: Regarding RQ1 and RQ2, participants were asked to think about the various news values (timeliness, proximity, prominence, impact, conflict, unusual nature, helpfulness and entertainment/celebrity) and rank them on a five-point Likert scale (Strongly Agree, Agree, Neutral, Disagree, Strongly Disagree) about the degree to which the news values affect their posting.

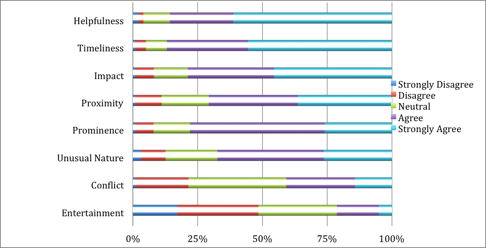

Slightly more than 60 percent of journalists strongly agreed they consider helpfulness as a consideration for posting to Facebook, followed by timeliness at 55 percent; impact, 45 percent; proximity, 37 percent; prominence, 25.8 percent; unusual nature, 26 percent; conflict, 14 percent, and entertainment, 5.4 percent.

FIGURE 1. JOURNALISTS SURVEYED RANKED HELPFULNESS AS THE TOP NEWS VALUE FOR FACEBOOK.

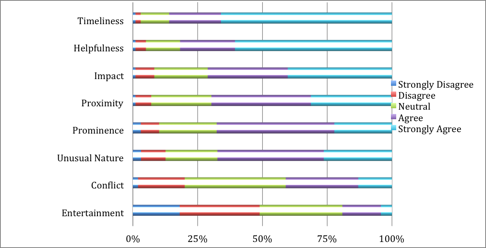

Timeliness ranked first for Twitter with 65.9 percent indicating strong agreement as a consideration when they post stories or links. Helpfulness rated second at 61 percent, followed by impact, 40 percent; proximity, 31 percent; prominence, 22 percent; unusual nature, 26 percent; conflict, 13.2 percent, and entertainment, 4.3 percent.

FIGURE 2. JOURNALISTS SURVEYED RANKED TIMELINESS AS THE TOP NEWS VALUE FOR TWITTER.

Analysis through one-sample t-tests of news values correspond with the descriptive data between the top news values for Facebook and Twitter. Using 3 as the benchmark value, the researcher determined that news values with a higher score than 3 are decidedly used by journalists to determine news content. Helpfulness ranked higher for Facebook at 4.42, but timeliness ranked higher for Twitter at 4.48. By contrast, entertainment ranked the lowest for both at 2.76 for Facebook and 2.75 for Twitter.

Relation of news values

The researcher chose to run t-tests to determine relationships between the importance of news values on both the Facebook and Twitter platforms. The paired t-tests compared specific news values to one another.

For postings on Facebook, impact (M=4.14, SD=.97) ranked slightly higher than conflict (M=3.32, SD=.99) when journalists post news items. Significance was indicated for the news value of impact, t(92)=6.8, p<.01. Impact ranked slightly more important than unusual nature (M=3.80, SD=1.03). However, when comparing helpfulness and impact, journalists place slightly more importance on helpfulness (M=4.42, SD=.86) than impact (M=4.13 SD=.99). Significance was found when comparing helpfulness and impact, t(91)=3.02, p<.01. These results suggest that journalists still rely on traditional news values and gatekeeping to decide which news items to post to Facebook. Helpfulness, an important consideration for helping readers live their daily lives, rated higher than impact, but when impact is compared to unusual nature, journalists choose items that have an impact on their local community. Also on Facebook, significance (t(92)=3.30, p<.01) was found for journalists using timeliness as a news value. Journalists were more likely to use timeliness (M=4.34, SD=.89) than proximity (M=3.96, SD=1.02).

On Twitter, significance was found between the choice of conflict and entertainment celebrity (t(83)=4.63, p<.01) and significance was identified between timeliness and proximity, t(90)=6.03, p<.01) Journalists were more likely to post news items identified with timeliness (M=4.47, SD=.86) than proximity (M=3.89, SD=.91). Significance also was identified between helpfulness and impact (t(90)=5.23, p<.01). Journalists were more likely to post items involving helpfulness (M=4.5, SD=.86) than impact (M=3.4, SD=1.02). Journalists also are more likely to post items involving conflict (M=3.3, SD=.98) than entertainment/celebrity (M=2.8, SD=.99).

These results suggest the traditional news values remain important, and because of Twitter’s immediacy, timeliness remains the top news value. Even though reporters and editors serve a local community, timeliness carried more significance than proximity.

“Breaking news or information that has a timeliness factor needs to be posted right away to either Facebook or Twitter, or both,” wrote one journalist in the open-ended portion of the survey. Another journalist wrote that social media offers a chance to let the public know the reporters are on the scene and working on stories. “Then you can report on it traditionally and post links to updates and a link to the full story when it has been investigated and written.”

Journalists surveyed for this study replied with specific examples related to how they use the news values to determine social media placement in their publications. Specific examples help researchers determine the current practices in the field.

“For my organization, proximity and helpfulness take on special significance. My print newspaper, although a daily, is heavily focused on our local communities. Because we have no revenue stream attached to our social media and little attached to our online/mobile platform, our primary goals with all of these products is to drive traffic to the print product and enhance our brand.”

“The news values are the same as those of traditional print. But the most important item (which was absent from your survey) is monetization. We publish a daily newspaper from which we derive clear revenue. Our website does not have an effective business model at this time and is probably undermining our print readership.”

“I don’t consider there to be a significant difference in news values between social media and print or web. News is news.”

One journalist said the immediacy of social media allows him to quickly disseminate items classified under the helpfulness news value. He said Facebook, in particular, allows for getting the news out quickly to his community because if he waited to publish in the daily paper, the item would no longer be useful or timely to his readers.

Regarding RQ3, would a journalist’s age and level of experience influence his or her decision to post news content to social media platforms, the tests revealed mixed results. No significance was found to exist among the levels of experience through the ANOVA test.

However, independent t-tests revealed significance, (t(27)=2.06, p<.05) between younger journalists, ages 21-30, and older journalists, ages 61 and up, for their consideration to post items of prominence to Facebook. Younger journalists (M=4.20, SD=.957) were more likely to post items of prominence to Facebook than older journalists (M=3.20, SD=1.095). No other statistical significance was found between the older group and younger group of journalists, which indicates that age may not be a deciding factor for the gatekeeping function for all the news values.

However, statistical significance (t(39)=2.28, p<.05) was found when comparing the age groups of 21-30 with 41-50 with regard to their consideration to use timeliness and impact as values for posting to social media. Younger journalists, ages 21-30, (M=4.68, SD=.627) were more likely to cite timeliness as a news value for Facebook than middle-aged journalists, ages 41-50, (M=4.00, SD=1.317). Significance also existed for the decision to post items involving impact to Twitter for the younger journalists, (t(39)=1.484, p<.05). Younger journalists (M=4.40, SD=.866) also were more likely to cite impact as a decision for posting to Twitter than middle-aged journalists (M=3.75, SD=1.125). No other statistical significance exists between the younger and middle-aged groups.

With regard to RQ4 in the open-ended section of the survey instrument, the researcher asked respondents about their publication’s social media policies regarding posting. Forty-four journalists indicated that their publications do not have limitations or a written policy about what they can post, and 28 indicated that they do have a policy.

One journalist who identified as an employee of the Rapid City Journal posted the newspaper’s policy that the paper drafted after consulting the guidelines set by the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, the Missoulian and the Wisconsin State Journal. The policy includes items reminding the staff to verify their information before posting and remaining objective when interacting with political parties on social media. The policy also encourages the journalists to remain cautious about retweeting content from user-generated sources so that their retweets are not taken as endorsements. Employees also may not post unpublished photos, audio or video gathered by reporters unless an editor has approved live-tweeting or live-blogging.

A few who indicated they do not have limitations expanded their answers to include reasons why. “We do give some thought to holding in-depth and exclusive stories until after they appear in print,” one journalist wrote. Another wrote, “There are no concrete limitations. We have our reporters and our online editor use common sense when posting.”

Several journalists also raised the question of whether posting to social media would affect their newspaper’s business model or drive traffic to their website, which is behind a paywall. “In the absence of a clear revenue stream, we should only be driving readers to and not away from our print product,” one editor wrote.

DISCUSSION

Journalists use the gatekeeping method for determining the newsworthiness of content for the legacy media, so it should follow that consciously or subconsciously they use the same method for posting to social media. Journalists at publications of under 25,000-circulation, 25,000-100,000 circulation and 100,000-plus circulation all viewed blogging as an extension of traditional reporting (Sheffer & Shultz, 2009). Thus, differences in circulation sizes as well as platforms may not make a difference in regard to traditional journalistic practices.

Cassidy (2006) and Singer (1997, 2005) both suggested that print-based routines remained prevalent in the online world, and Brems (2014) suggested that the routines are becoming adapted to speed and space. The speed of social media may help to push the boundaries of the traditional deadline and publication schedules as reporters and editors are no longer bound to a schedule for publishing content. Breaking news, for instance, no longer has to wait for the morning paper.

Twitter seemed to attract journalists who wanted to post breaking news or timely links, but Facebook seemed to drive opportunities to engage or connect with the newspaper’s community. Helpfulness ranked first as a news value for Facebook, followed by timeliness, while timeliness ranked first on Twitter followed by helpfulness. Both Twitter and Facebook allow newspapers to quickly share information that qualifies as both timely and helpful to their communities. For instance, if a traffic accident closes an interstate or major highway, a reporter or editor can help their public determine an alternate route immediately, unlike years ago when newspapers had to wait until the next publication cycle. Helpfulness also allows journalists to post updates about weather events, such as reports of confirmed tornadoes or flash floods. This news value also gives readers immediate information about shelters in times of a weather crisis. Facebook’s visual nature enhances the posts about helpful community information by enabling journalists to post a photo from a scene or a graphic that gives additional information.

One journalist replied in the survey that he could easily get information out to his audience that was both timely and helpful in the case of an accident. In that case, the journalist again is acting as the gatekeeper by deciding to post helpful information immediately rather than waiting to disseminate that information in the traditional print product. The item would still be disseminated to the public, but the action of immediately posting it allows the gatekeeper to control the flow and timing of that information to the public.

In a sense, this feeling of “helpfulness” can create another form of community online. Much like knowing one’s neighbor, the community still needs the news and shared shreds of information (Hatcher & Reader, 2012). Formal and informal measures help the community to produce and supply information to the public (Hatcher & Reader, 2012), much like the notion of helpfulness as a news value when news organizations and their audience engage in social media postings about things happening in the community. The same may hold for the news value of impact, which alerts a community to an issue that may affect it. In this day and age of vanishing geographic communities, what may have an impact on the audience in a larger population area also may have an effect on those in a smaller area. The only separation now comes in the form of a screen as Americans are increasingly living their lives online, and 63 percent of Americans consume news through Facebook and/or Twitter (Barthel, Shearer, Gottfried & Mitchell, 2015).

Timeliness allows reporters and editors to immediately update their readers about everything from traffic incidents to a verdict from a high-profile local trial. Timeliness became a hallmark for Twitter as the company described itself as a “real-time information network” (Twitter, 2011).

Additionally, Boyle & Zuegner (2012) found the largest focus of tweets for mid-sized papers focused on local news. In this study, proximity, long a hallmark for local news, ranked third for both platforms. One has to wonder if the age of a mediated form of community might push that news value down slightly as community may no longer be defined as a specific location, but rather a specific audience that may extend well beyond geographical confines. Social media could redefine that traditional definition of proximity beyond a specific area.

With the results showing a tendency to use traditional news values for postings to Facebook and Twitter, Cassidy’s conclusion holds that online and print journalists are not too far separated on their perceptions on gatekeeping and news values (Cassidy, 2006). The journalists queried in this survey work for daily newspapers of circulations under 30,000 that are delving into using social media as a way to connect with their audience, disseminate content and possibly drive the audience back to either the online site or the traditional print product.

Although a few significant differences were found between the youngest age group and the oldest age group in regard to the news value of prominence, journalists as a whole did not have differences for levels of experience. The absence of significance may back up Cassidy’s finding that no differences in the gatekeeping function exist between online and print journalists. Journalistic training, whether conducted on the job or in a classroom, does not seem to matter about the perception of the news values for social media. Cassidy (2007) also wrote that research pertaining to the sociology of news values suggests that journalists “internalize the norms and values of the profession, as well as those of the organization for which they are working” (Cassidy, 2007, pg. 18). Additionally, Shoemaker & Vos (1996) found that patterned routines may be repeated as journalists perform their jobs. Thus, one has to wonder if the posting of content falls under the guise of a patterned routine or a spontaneous response, and if that response, in fact, controls the gate or allows the gate to swing open toward Bruns’ model of gatewatching.

As people continue to increase their reliance on social media for daily activities, the difference for ages and posting may not exist. Younger journalists may correspond with social media usage rates of the population ages 18-29 where 90 percent use social media (Perrin, 2015). Social media usage among those ages 65 and up also tripled from 2010 at 11 percent to 35 percent five years later (Perrin, 2015).

Although Cassidy’s study did not note significant differences between print and online journalists, Bruns’ gatewatching model could be applied to social media because of the transparency involved when reporters and editors interact with their audience on social media. For instance, he mentioned that readers are “encouraged” to check a reporter’s sources, and indeed, if a reporter posts updates from stories-in-progress, an argument could be made that it is a measure of transparency (Bruns, 2003, pg. 36). Carvin, the former NPR reporter, used Twitter during the Arab Spring to report in real time and show his audience his sourcing, and thus the transparency of reporting (Briggs, 2013). Lasorsa, Lewis & Holton (2012) surmised that transparency may already be occurring in microblogging, such as Twitter, because journalists post in real-time to an audience that sees their sourcing and reporting (Lasorsa, Lewis & Holton, 2012, p. 24).

Additionally, the lack of policies for posting, as mentioned in RQ4, suggests the newspapers trust the established routines of gatekeeping as a way to determine the news content. Brems (2014) asserted the journalist still remains a trained figure for the public to use as guidance for content, whether online or anywhere else (Brems, 2014).

Limitations of the study and future research

These results of a small sample in this pilot study indicate a snapshot of current practices of posting to social media platforms. The researcher plans to conduct additional surveys with media organizations such as the Society of Professional Journalists or the American Society of Newspaper Editors and state press associations in hopes of getting a larger response. The researcher also plans to use incentives to bolster the response rate. Sheehan (2001) found response rates when the first interoffice messaging system was introduced recorded a mean response rate of 61.5, but the rates have dropped to 24.0 in 2000 (Sheehan, 2001).

Future research also could examine whether individual or routine forces (Shoemaker et al., 2001) play a role in posting to social media. Another study could address the notion of gatewatching and apply that model to reporting in real time on Twitter. Additional research could be conducted via content analysis of several circulation groups (1-10,000, 11,000 to 19,999 and 20,000 to 30,000) to determine the types of content news organizations post.

Because social media evolve frequently in regard to platforms and usability, perceptions of journalists and their view of news values on social media should be gathered regularly to determine the current practices and applications to the existing theories of gatekeeping.

CONCLUSION

Today’s community newspapers, specifically those with a circulation of 30,000 or less, use social media for both reporting and news dissemination, and the trend likely will continue as readers use Facebook and Twitter as social networks and coincidentally for their news reading. Consciously or not, journalists, whether an editor or a reporter, remain the gatekeeper in deciding which types of items to post to Facebook or Twitter. The pilot study, although a small snapshot of community newspapers, suggests journalists still use traditional news values to determine posting to social media. As such, the reporters and editors who post remain the traditional gatekeepers because they are using factors to determine what they think their audience wants to see, much like they do for determining the types of stories to place on Page 1. News has to be timely and helpful to have an impact on a local community because readers turn to social media several times a day for updates from their friends and their media sources. In a way, social media continues the cycle of how newspapers involve their communities and engage readers for comments and interaction through community forums, reader contests and even reader submissions of stories. The difference is that social media provides the element of immediacy as readers can tweet back to the paper or individual reporters, and they can comment on Facebook status updates.

As social media become an important journalistic strategy for news organizations, large and small, future studies should continue to examine the relationship between the journalist as the gatekeeper and if traditional values still hold.

REFERENCES

- Atagana, M. (n.d.). CNN’s head of social news: Twitter forces journos to report the news better. Memeburn,Tech-savvy insight and analysis. Retrieved February 26, 2013, from http://memeburn.com/2012/11/twitter-forces-professoinals-to-report-the-news-better-cnns-head-of-social-news/

- Barthel, M., Shearer, E., Gottfried, J., & Mitchell, A. (2015).The Evolving Role of News on Twitter and Facebook.Pew Research Center’s Journalism Project. Retrieved 8 March 2016, from http://www.journalism.org/2015/07/14/the-evolving-role-of-news-on-twitte…

- Bass, A.Z. (1969). Refining the ‘gatekeeper’ concept: A UN radio case study. Journalism Quarterly, 46, 69-72.

- Bastos, M.T. (2014). Shares, Pins, and Tweets. Journalism Studies, DOI:10.1080/1461670X.2014.891857

- Brems, C. (2014, December). The connected journalist: Social media and the transformation of journalism practice. In ELECTRONIC PROCEEDINGS (pp. 18-34).

- Bruns, A. (2003). Gatewatching, not gatekeeping: Collaborative online news. Media International Australia Incorporating Culture and Policy: quarterly journal of media research and resources, 107, pp. 31-44.

- Cassidy, W.P. (2006). Gatekeeping similar for online, print journalists. Newspaper Research Journal, 27(2). 6-23

- Cassidy, W. P. (2007). Online news credibility: An examination of the perceptions of newspaper journalists. Journal of Computer‐Mediated Communication, 12(2), 478-498.

- Chibnall, S. (1977). Law-and-order news: An analysis of crime reporting in the British press. London: Tavistock.

- Cohen, B.C. (1963). The press and foreign policy. Westport, CT: Greenwood.

- De Maeyer, J. (2012). The Journalistic Hyperlink, Journalism Practice, 6:5-6, 692-701.

- Dimitrova, D., Connolly-Ahern, C., Williams, A.P., Lee Kaid, L., and Reid, A. (2003). Hyperlinking as gatekeeping: Online newspaper coverage of the execution of an American terrorist. Journalism Studies 4(3), 401-414.

- Deuze, M. (1998). The WebCommunicators: Issues in research into online journalism and journalists. First Monday, 3(12). doi:10.5210/fm.v3i12.634

- Gans, H.J. (1979). Deciding what’s news. New York: Pantheon.

- Galtung, J. & Ruge, M. (1965). The structure of foreign news: The presentation of the Congo, Cuba and Cyprus crises in four Norwegian newspapers. Journal of International Peace Research 1, 64-91.

- Gieber, W. (1956). Across the desk: A study of 16 telegraph editors. Journalism Quarterly, 33(4), 423-432.

- Givens, D. (2012) Mr. and Mrs. John Doe announce the engagement of … A study in the decline of reader-submitted content in four Eastern Kentucky community newspapers, Grassroots Editor, Fall-winter 2012, 19-24.

- Grant, A. (2012, October). Seven functions of social media for journalists. The Convergence Newsletter. Retrieved March 12, 2013, from http://sc.edu/cmcis/news/convergence/v9no.8

- Greer, J. and Yan Y. New Ways of Connecting with Readers: How Community Newspapers are using Facebook, Twitter and other tools to deliver the news. Grassroots Editor 51(4), 1-7.

- Halloran, J.D., Elliott, P., & Murdock, G. (1970). Demonstrations and communications: A case study. Baltimore: Penguin.

- Hatcher, J. A. & Reader, B. (2012).Foreword: New Terrain for Research in Communicty Journalism. Community Journalism, 1(1), 1-10.

- Hermida, A. (2010). Twittering the news: The emergence of ambient journalism. Journalism Practice, 4(3), 297-308.

- Hurricane Sandy and Twitter | Project for Excellence in Journalism (PEJ). (n.d.). Project for Excellence in Journalism (PEJ) | Understanding News in the Information Age. Retrieved March 13, 2013, from http://www.journalism.org/index_report/hurricane_sandy_and_twitter

- Johnstone, J, Slawski, E., & Bowman, W. (1972) The professional values of American Newsmen. Public Opinion Quarterly, 36(4), 522-540.

- Lasorsa, D., Lewis, S., & Holton, A. (2012). Normalizing Twitter. Journalism Studies,13(1), 19-36.

- Lewin, K. (1947). Frontiers in group dynamics II. Channels of group life; social planning and action research. Human relations, 1(2), 143-153.

- Meraz, S. (2009). Is there an elite hold? Traditional media to social media agenda setting influence in blog networks. Journal of Computer‐Mediated Communication, 14(3), 682-707.

- Mitchell, A., Kiley, J., Gottfried, J. and Guskin, E. “The Role of News on Facebook: Common yet Incidental.” www.journalism.org. Retrieved October 24, 2013.

- Patel, M. and Maness, M. “Friends, Followers and Feeds: How news flows on Facebook.” www.knightfoundation.org. Retrieved October 24, 2013.

- Perrin, A. (2015).Social Media Usage: 2005-2015.Pew Research Center: Internet, Science & Tech. Retrieved 2 March 2016, from http://www.pewinternet.org/2015/10/08/social-networking-usage-2005-2015/

- Rich, C. (2010). Writing and Reporting the News: A Coaching Method (6th edition). Boston: Wadsworth.

- Rosentiel, T. (n.d.). How Mainstream Media Outlets Use Twitter: Content Analysis Shows an Evolving Relationship. www.journalism.org. Retrieved March 13, 2013.

- Rosenberry, J. Circulation, Population Factor into Social Media Use. Newspaper Research Journal, 34(3), 86-100.

- Sheehan, K. B. (2001), E-mail Survey Response Rates: A Review. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 6:0. doi:10.1111/j.1083-6101.2001.tb00117.x

- Sheffer, M.L. and Schulz, B. (2009, August 5). Are Blogs Changing the News Values of Newspaper Reporters?. AEJMC National Convention. Paper presented at AEJMC, Boston, Mass.

- Shephard, M. (2013, February 23). Q&A: NPR’s Andy Carvin on tweeting and tweeting and tweeting. The Toronto Star [Toronto], p. WD7.

- Shoemaker, P.J., Eichholz, M., Kim, E., & Wrigley, B. (2001). Individual and routine forces in gatekeeping. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 78(2), 233-246.

- Shoemaker, P.J., & Reese, S.D. (1996). Mediating the message. NY: Longman.

- Shoemaker, P. and Vos, T. (2009). Gatekeeping Theory. NY: Routledge.

- Singer, J.B. (1997). Still guarding the gate? The newspaper journalist’s role in an on-line world. Convergence: The Journal of Research into New Media Technologies, 3 (1), 72-89.

- Singer, J.B. (2005). The political j-blogger: “Normalizing” a new media form to fit old norms and practices. Journalism 6(2), 173-198.

- Snider, P.B. (1967). ‘Mr Gates’ revisited: A 1966 version of the 1949 case study. Journalism Quarterly, 44(3), 419-427.

- Stromback, J., Karlsson, M., and Hopmann, D. (2012). Determinants of News Content: Comparing journalists’ perceptions of the normative and actual impact of different event properties when deciding what’s news. Journalism Studies, 13(5-6), 718-728.

- Weaver, D.H., Beam, R.A., Brownlee, B.J., Voakes, P.S., & Wilhoit, G.C. (2007). The American journalist in the 21st century: U.S. newspeople at the dawn of a new millennium. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Weaver, D.H., & Wilhoit, G.C. (1986). The American journalist: A portrait of U.S. news people and their work.Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Weaver, D.H., & Wilhoit, G.C. (1996). The American journalist in the 1990s: U.S. newspeople at the end of an era.Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Westley, B.H., & MacLean, M.S., Jr. (1957). A conceptual model for communications research. Journalism Quarterly, 34, 31-38.

- White, D. M., & Dexter, L. A. (1964). People, society and mass communications. Free Press.

- White, D. M. (1950). The “gate keeper”: A case study in the selection of news (pp. 143-159). na.

About the Author

Leigh Landini Wright is an assistant professor of journalism at Murray State University.