Aaron Chimbel, a faculty member at the TCU Schieffer School of Journalism, led a workshop for community journalists in September 2010 on shooting and editing simple video stories using the Flip video camera. Below are his handouts from the workshop.

Here’s a story that’s easy to localize: The Texas Tribune has a story on the health of inmates in Texas county jails. Sheriffs say that sickness among inmates – often made worse by chronic ailments and drug or alcohol addiction – rivals the illness rates in state lockups, despite the fact that counties house only half the number of inmates. There are no state standards for health care in county jails, and illnesses can spread quickly and are expensive for jail budgets. You may find that it’s a costly and significant problem in your own county.

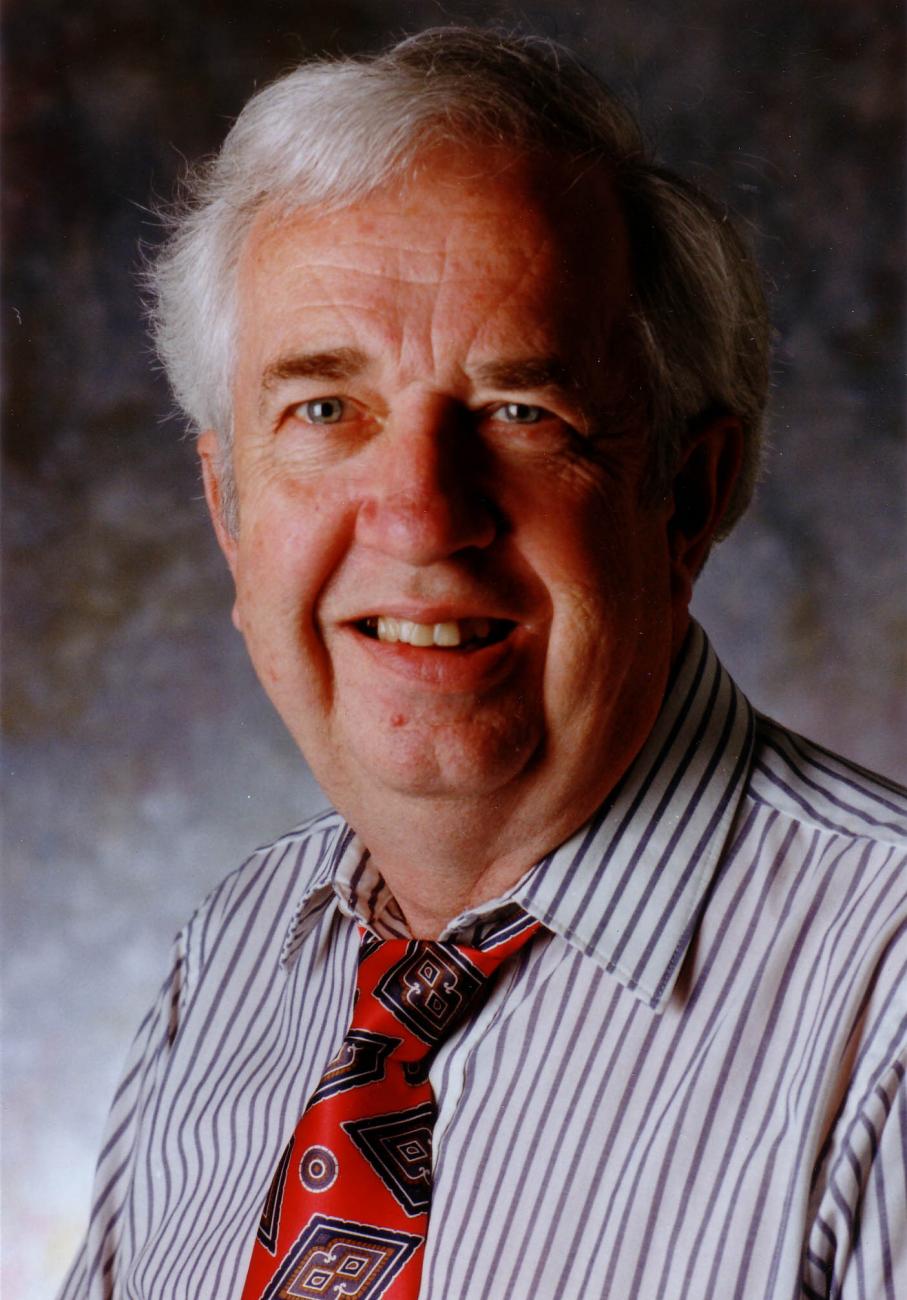

This week the Center, and indeed all of community journalism, lost a friend and mentor.

Phil Record, long-time Star-Telegram editor and ombudsman and for the past decade professional in residence in journalism ethics at the Schieffer School, died of a heart attack Sunday evening. Phil was a consultant in ethics for the Center and had spoken at several workshops and answered queries in our Ask an Expert service.

Phil represented the best of what it means to serve our readers. He was committed to honesty, fairness, accuracy, and the highest standards of ethics in our profession.

He will be missed at the Center, but he will also be missed by all newspeople everywhere who relied on his wise advice and his insights on difficult ethical dilemmas.

Update: The post below led to a research project regarding fair use and photographs taken from social networks and used for news purposes. The results largely confirmed the suspicions of this post, that using a photo is not fair use, with some exceptions. The article was published in the Journal of Telecommunications and High Technology Law in 2012, and a full, free, downloadable version is available here: http://www.jthtl.org/content/articles/V10I1/JTHTLv10i1_Stewart.PDF

It's a question I've heard from our student newsroom twice in the past couple of weeks, and I've heard some chatter on Twitter on it as well from @hartzog, @derigansilver and @johnrobinson. "Can I use this photo I found on facebook in my news story?"

The scenario usually unfolds like this: A story breaks on a relatively unknown person, and without a mug shot or an AP wire photo available, intrepid reporters turn to facebook or MySpace for photos of this person. Sound familiar? If you remember Eliot Spitzer's (ahem) friend from the high-end prostitution ring from a couple of years ago, or the red-haired Russian spy more recently, the first photos you saw of them were, most likely, from MySpace (in the case of Ashley Dupre) or facebook (in the case of Anna Chapman) accounts.

I'm going to guess that the reporters who dug up these photos didn't get them through a publicist or ask for, much less receive, any permission to publish them. This approach comes from the classic Internet culture of "I found it online, and it's free, so I must be able to use it." And that worked out so well for Napster, right?

Two issues come up in this scenario – one legal, one ethical. Legally, I see a huge copyright issue here. Whoever took that photo has a copyright in it, attaching the moment the photo button was pushed. It's an original work of authorship in a fixed medium of expression. The copyright act couldn't be clearer on this.

The question is, does it just become public domain by virtue of being posted on facebook? Of course not. If you put up a photo of your lost dog on a coffee shop bulletin board, does that photo become public domain, able to be used anywhere by any person who wants to grab it? If you leave a photo album on your coffee table, can any guest to your home borrow a photo and use it for whatever purposes they want?

So, moving online, is that unfortunate photo of you in the sombrero from college tagged on someone else's facebook account fair game for use by anyone – friend or otherwise – who can access it? Perhaps they could make a nice greeting card from it?

And I don't think this qualifies as fair use either. A use for news purposes would meet the first threshold for review under fair use guidelines, but under the four-part balancing test applied by courts in looking at fair use, I don't see how any one favors the republisher: The use is for-profit, the entire photo is used, it most likely is a significant element of the news story, and it harms the market for the original copyright owner by giving away for free what the owner could legally sell.

So how, you may ask, did the photos of Ashley Dupre and Anna Chapman wind up with news stories about them? Chances are, reporters grabbed and posted, and nobody asked any questions afterward.

Think about this: What if someone had? What if the people in these photos, or the people who took them, felt wronged about the use of their facebook photos? What remedies would they have?

Invasion of privacy is, most likely, not an option. As you probably know by now, you don't have any reasonable expectation of privacy in photos or statements made on the Web. It's a bit like posting the lost dog poster in the coffee shop or putting out your photos on the coffee table – you give up your right to claim intrusion when you invite public people to see them. As my privacy-expert friend Woody Hartzog points out, you may have a (warning, legal jargon ahead) promissory estoppel claim through facebook's Terms of Service – that is, friends promise not to violate others' copyrights (see the Terms of Service, Part 5, first item) as a term of signing on to facebook, and breaking that promise means one could be liable for damages incurred as a result of that violation. The MySpace terms present a similar quandary.

[For what it's worth, the facebook Terms of Service DO allow facebook a "non-exclusive, transferable, sub-licensable, royalty-free, worldwide license" to use the photos you upload. These do not carry over to all users, of course. But creepy, eh?]

But that's not the strongest argument. If the person whose photo was used wants to make your life miserable, he or she could make an easy copyright infringement case against you. All they'd have to do is find the friend who took the photo, ask him or her to file for a copyright on it, then go to federal court and ask a judge for damages. Minimum statutory damages are $750 per violation, but I could see a photo that gains widespread attention bringing in more than that. Why shouldn't the person who took that photo be entitled to the same kind of protection that, say, a professional photographer should if somebody used his or her work without paying for it?

I'm not saying this is the most likely scenario. The easiest remedy for someone to take to remove a photo from unlawful republication would be to issue a takedown notice to the ISP under the Digital Millennium Copyright Act. But that won't make them any money, nor will it satisfy their lust for revenge.

People who feel hurt will find ways to hurt you back, and they have all the legal rights they need if you violate their copyright by reposting a photo. So don't do it.

Instead, take the easy and obvious route: Ask permission. Get it in writing (keep your email messages). Only reprint when you know the copyright holder has consented. And if you can't get that consent – it's probably a good thing you didn't publish it, right?

Onto the ethical ramifications here. While facebook users may not have any privacy rights guaranteed by the law, they do have reasonable belief that the service is to share their information with friends. As a journalist, would you have any ethical issues with rifling through the photo album of a citizen after he or she had been arrested or implicated in some huge news? Consider the following from the SPJ Code of Ethics:

"Recognize that private people have a greater right to control information about themselves than do public officials and others who seek power, influence or attention. Only an overriding public need can justify intrusion into anyone's privacy."

And:

"Show good taste. Avoid pandering to lurid curiosity."

Consider the photos of Ashley Dupre in a bikini. Is there overriding public need for this information? Or is this pandering to lurid curiosity?

In short, facebook photos aren't posted with the intent of becoming public domain and usable for any purpose, news or otherwise. Journalists should know better. And for those who don't, some day, the hammer will come down. I tell my students, "don't let this be you." I offer the same advice to journalists everywhere.

U will ROTFL when you and ur BFFs from the paper check this out. It’s a CWOT, but it’s GR8.

Andrew Chavez, associate director of the Texas Center for Community Journalism, speaks at a TCCJ Watchdog Workshop on Web applications that can be useful in investigative reporting.

Typically we point to specific articles in Around the Web. But here’s something different: The Center for Rural Strategies http://www.ruralstrategies.org in Kentucky publishes some fascinating research in its online newsletter The Daily Yonder http://www.dailyyonder.com. It’s all about rural counties in the United States and much of it applies to Texas. The latest http://www.dailyyonder.com/ba-divide/2010/10/17/2995, for instance, is about the serious lack of university degrees in rural areas and what that means for economic development. To keep abreast of the latest research, much of which you can localize for your newspaper if you’re located in a rural area, go to the Daily Yonder’s Twitter page

(Editor’s note: In this thinkpiece, Jerry Grotta, associate director of TCCJ, reacts to the news that the Audit Bureau of Circulations has changed the way newspaper circulation is counted, beginning Oct. 1. The changes include newspapers now being able to count subscribers more than once — a subscriber may be counted once for a print subscription, once for an e-reader subscription, etc. This also includes online, mobile and other subscriptions. Also, newspapers may include products published under a different name in their total average circulation.)

Several years ago I heard the following at a conference on newspaper circulation:

The owner of a newspaper was hiring a new publisher. He narrowed the candidates to three current employees — the advertising manager, the editor and the circulation manager. As a final step, the owner conducted a three-hour interview with each candidate. His final question was: “How much is two and two?”

The advertising manager answered: “Two and two is four. Never less, never more.” The publisher said, “Very precise.”

The editor said, “Well, two plus two is four. But two twos side-by-side is 22. And two divided by two is one.” The publisher said, “Very creative.”

The circulation director leaned toward the owner and whispered, “How much do you want them to be?”

And that sums up the history of newspaper circulation.

Here’s how Timothy Hughes reports on what John Campbell said about a competitor’s circulation:

The earliest comment on newspaper circulation in America was by publisher John Campbell in his Boston News-Letter of 1719. He notes that “… he cannot vend 300 at an impression, tho’ some ignorantly concludes he sells upwards of a thousand…”

Did newspapers really lie? Here is why the Audit Bureau of Circulations was formed in 1914:

For more than 90 years, the Audit Bureau of Circulations (ABC) has served as the trusted industry standard in audited circulation figures. This commitment began at the turn of the century, a time when unscrupulous business practices dominated the publishing industry and made it difficult for advertisers and publishers to form effective partnerships.

As long as circulations were growing through the first half of the 20th century, newspapers were reaping big profits. However, the household penetration had been declining, from 100+ percent in the 1950s to about 30 percent today.

And then actual circulation began to decline. In just the past decade, weekday circulation has fallen 28.4 percent between 2000 and 2010, while Sunday circulation has declined 30.4 percent.

Why?

While television still dominates overall as a source of news, it has declined from more than 70 percent in 1991 to less than 60 percent in 2010.

Radio declined from 54 percent in 1991 to 34 percent in 2010.

And newspapers dropped from 55 percent in 1991 to 31 percent in 2010. That’s a 44 percent decline.

Where did all the viewers, listeners and readers go?

To the Internet.

Online as a news source was first measured in 2004, with 24 percent. In 2010, it has risen to 34 percent — or higher than newspapers and radio.

However, 44 percent get their news from some form of Web and mobile media, second only to television and 30 percent more than from newspapers.

So what are newspapers doing? Trying frantically to find new ways to measure circulation and readership, such as including hits on their websites, such as “requested” verified circulation, and “targeted” circulation (where people do not object to having newspaper products delivered to their homes).

How will this affect newspapers? For one thing, it will make “audited circulation” much more complicated. The overall effect on “circulation” numbers is still uncertain.

But one thing is certain. The old newspaper model is broken.

Nearly 40 years ago, Richard Maisel said in an article in Public Opinion Quarterly:

The (traditional) mass media are actually shrinking in size relative to the total economy.

And I wrote in an article in Journalism Quarterly in 1974:

If the newspaper is to survive in the decades ahead, it must do so on the basis of offering the consumer a product which fulfills the needs of the consumer.

We can see in the continued decline in the circulation and readership of major daily newspapers that the industry hasn’t done a very good job of producing a product “which fulfills the needs of the consumer.”

But how are community newspapers doing?

A whole lot better than the big dailies!

Here’s how the National Newspaper Association describes the situation:

Today, the distinguishing characteristic of a community newspaper is its commitment to serving the information needs of a particular community. The community is defined by the community’s members and a shared sense of belonging. A community may be geographic, political, social or religious. A community newspaper may be published once a week or daily. Some community newspapers exist only in cyberspace. Any newspaper that defines itself as committed to serving a particular community many be defined as a “community newspaper.”

Despite the emergence of new information technologies such as the Internet, community newspapers continue to play an important role in the Information Age. Over 150 million people are informed, educated and entertained by a community newspaper every week. Moreover, the value of community newspapers continues to grow as they seek new ways to serve their readers and strengthen their communities.

Why does the future look brighter for community newspapers? People are interested in community news, but television, radio stations, and large daily newspapers can’t give comprehensive coverage of every community in their markets.

Community newspapers can . . . if they:

- Focus their coverage on the local community – who, what, where, when, why and how.

- Offer people in the community a variety of well-designed sources for their local news and advertising from your newspaper (the printed version, a web version, etc.)

- Talk to – and listen to – the people in the community. How do they feel about your newspaper? What do they like and dislike about it?

If you do not do this, somebody else will!

For The San Angelo Standard-Times and its on-line version, GoSanAngelo.com, newsgathering in the Internet age is not show business. However, technology has put the newspaper in a closer competition with traditional electronic media. While metro papers are suffering, the San Angelo paper is attracting new readers — despite a sluggish economy

Tim Archuleta, editor of The San Angelo Standard-Times and GoSanAngelo.com, said, “Being able to serve up content in lots of different ways gives us a new platform to reach audiences, but in the end, we’re going to succeed by being true to our traditional values. It’s about serving our communit

Archuleta has worked in journalism for 25 years, with stints in New Mexico, Michigan, California and Texas. He said the immediacy of news — with reader feedback — is the biggest change in newspaper today, with the advent of online versions and no more waiting 24 hours to break a story.

“When you look at the transition from just being print to going online, and becoming true multi-media journalism, you have to remember that it’s not about perfection.” Archuleta said. “Especially online, it’s about progress. You want folks (reporters and editors) to experiment.”

Some things don’t change. The Standard-Times reporters serve a mid-size, somewhat secluded West Texas city and the 16-17 surrounding counties, just as they have in much of the paper’s 125-year history. Although a San Angelo reporter may travel 200 miles one way to cover his or her beat, two stories with worldwide interest practically fell into their lap

The State of Texas raided a polygamist compound south of San Angelo in Eldorado, taking hundreds of children from parents in the sect after allegations of child abuse and underage, arranged marriages. In effect, the FLDS (Fundamentalist Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints) case became the nation’s largest child custody case, with more than 400 children displaced.

See coverage: http://www.gosanangelo.com/news/news/local/FLDS/

“We were driving the story, and I am proud of our team for that.” He said. “You will hear me mention the FLDS time and time again in our story of making the transition from print to being also online. What that showed us was we had to go online first. We had lots of media competition. The story was developing so quickly …”

The paper’s stories were picked up by news organizations, including the Associated Press, and distributed worldwide in other papers, in addition to direct readership at the paper’s site.

“We just celebrated our second month going over two million page views,” Archuleta said. “We hit two million views earlier, but it was really driven by the FLDS investigation.”

A second story struck a chord with a special-interest audience, and soon readers around the world were talking about the logistics of long-distance lactation because of a San Angelo story.

“You can be first with breaking news. You can provide video. You can do things that you couldn’t do before,” he said. “If you don’t do it, someone else might.”

When the paper began its on-line version, five years ago, it didn’t know what to expect. In fact, management ran a full-page ad in the paper, touting when GoSanAngelo first hit one million page views — just two years ago.

“Think about the role that newspapers have traditionally played in communities. We’ve shaped our communities and this (on-line news) is just another example. Think about what it would be like if we didn’t have a way to help our readers move into a digital format. Our community won’t be left behind.”

The Standard-Times has not announced plans to monetize its content to date, although Archuleta predicts that is something all news organizations will explore. Archuleta and team are focused on providing an interactive experience, with many choices to attract and satisfy more readers — seven days a week. The print version includes five sections and typically 50 pages on any given Sunday, with an emphasis on local new

In Texas, football is king and the Internet is yet another means for The Standard-Times to feed that hunger. GoSanAngelo this year launched “Blitz,” a multi-media football guide teeming with data, statistics and photo gallerie

The paper also started “Morning Chat,” an online comment forum for readers to discuss topics of the day – with a strict set of guidelines, self-policed by the readers. It is not uncommon for a single discussion or “thread” to include 200 reader comments and/or contribution.

“We went through a period during the FLDS raid where we got a lot of bizarre comments on the website and it was to the point where it was sort of out of control. News agencies are still struggling with how to control comments,” Archuleta said.

The Standard-Times was also one of the first papers to shut down on-line comments and impose a time-out. The service began anew, after guidelines were posted beside the registration form.

Community journalism, by definition, is a vital part of a social community, so The Standard-Times also has social media visibility on Facebook — delivering shorter versions of stories and links to full stories. The paper’s Facebook page is followed by an impressive 25 percent of its readers.

The story on breast milk — with its tie to military — spread virally on Facebook and via the paper’s site, attracting readers all over the world.

“For the year, it was our top viewed story.”

So let’s assume somebody wants to set up an Internet-only competitor for your newspaper. Something that could deliver the same types of news you do, just online. A competitor for advertising dollars. Someone who would offer the news and photos and videos of your community, and probably at no cost to readers. You know how much it might cost another newspaper to come into town and set up a duplicate version of your operation – but how much would it cost an Internet start-up to come in and do exactly what you do, but do it online? Warren Webster, president of AOL’s Patch, which is doing just that, has a figure: 4.1 percent of what you are spending now, to duplicate everything you’re doing on the Web. Aaaarrrrgh! Check out this article. (And by the way: I talked with an editor at Patch last month, and she said they are already in the initial stages of getting ready to enter the Texas market.)