Abstract

The relationship between media consumption and attitudes about immigration is well established, but with a focus on national news outlets. The role of local media consumption is not as well understood. This study surveyed residents of Texas (N=316) which shares two-thirds of the United States’ border, and Ohio (N=322) which is less diverse and politically predictable. Reading Ohio newspapers predicted significantly less support for immigration; reading national newspapers, more support. Local TV viewing wasn’t significant.

Introduction

There is a long body of scholarship on the relationship between contentious social issues (i.e., abortion, race relations, immigration), news consumption, and attitudes about those issues (Kellstedt, 2003; Watson & Riffe, 2012; Price & Kaufhold, 2019). The role of ideological media consumption in this relationship, like Fox News Channel and MSNBC, is especially well-researched (Garrett, Carnahan & Lynch, 2013; Jahng, 2018; Dahlgren, Shehata & Strömback, 2019). Lesser understood, and of particular interest to those with an interest in this publication, is the role of local and community journalism sources with regard to contentious issues. A particularly salient one in the current political environment is immigration.

Since at least the start of the Reagan administration (Cornelius, 1981) immigration has been a prominent national political issue in the United States. Donald J. Trump made immigration the centerpiece of his run for the White House (Newport, 2015; Felter, Renwick & Cheatham, 2020). At his campaign kickoff, in June, 2015, he said, “When Mexico sends its people, they’re not sending their best. They’re bringing drugs. They’re bringing crime. They’re rapists. And some, I assume, are good people.” Trump talked throughout his campaign of building a border wall and instituting other, more rigorous measures to stem what he referred to as an “invasion” (Corasaniti, 2016; Reilly, 2016).

Despite polling data showing that immigration wasn’t a dominant issue to Republican voters that year, candidate Trump finished a close second to Senator Ted Cruz in the first-in-the-nation Iowa Caucus Feb. 1, and on Feb. 9, Trump won the second race by a two-to-one margin – the first primary, in New Hampshire (NBC News, 2016; New York Times, 2016; Pew, 2016). Trump campaigned for a comprehensive border wall, large-scale removal of undocumented immigrants already in the U.S. and tighter restrictions on travel from half a dozen primarily Muslim countries (Corasaniti, 2016). As President, Trump instituted policies to criminalize crossing the border without documentation, resulting in the controversial child separation policy (Rizzo, 2018).

Immigration reemerged as a major national issue in the second month of the Biden Administration as border crossings increased to the point that the Department of Homeland Security predicted a record year in 2021 for family immigration (Miroff & Sacchetti, 2021). Immigration detentions set records again in 2022 and 2023 and continued to grow into 2024 (TRAC Immigration, 2024). Both political parties made hay out of the issue as Republican and Democrat lawmakers paid separate visits to the border in March, 2021 – reporting very different perspectives of the same scene (Gamboa, Shabad & Gregorian, 2021; Phillips, 2021). In February 2024, both Biden and Trump visited the Texas border with Mexico, to argue for and against a Democrat-supported bill to secure the border (Despart & Melhado, 2024).

Of interest in this study is whether consuming local mainstream sources contrasts with the well-established pattern of ideological news consumption and attitudes on contentious issues. There is some divergence about the effect of exposure to ideological media sources. Some studies show that exposure to consonant media leads to ideological self-isolation and a reduction in exposure to opposing media (Stroud, 2007; Dahlgren, Shehata & Strömbäck, 2019). But other scholarship has found that exposure to agreeable positions fuels curiosity about opposing viewpoints, and that even consumers mostly practicing selective exposure are still often exposed to objective or dissonant media (Garrett, Carnahan & Lynch, 2013; Jahng, 2018; Dahlgren, Shehata & Strömback, 2019).

An important consideration is the outsized role of party identity in a host of variables relevant to this body of research: selective exposure to pro-attitudinal media; acceptance of, or skepticism toward, mainstream legacy media outlets; and cynicism about and distrust of science, including survey research. Most of the body of research on selective exposure and reinforcing ideology has focused on national partisan outlets, including conservative talk radio, ideological cable news outlets MSNBC and Fox News Channel, and social media echo chambers. But the role of local media consumption on ideological topics, like immigration, isn’t as well understood. Comparing, or contrasting, between local and partisan national media is the focus of this study.

Literature

Partisan Media

Partisan media, for more than a century, has had a national influence. Newspapers owned by William Randolph Hearst reported with a conservative bent, especially against President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal (Nasaw, 2001). Even before that, the Los Angeles Times, under Republican activist publisher Harrison Gray Otis, opposed organized labor and supported economic development. His son-in-law, Harry, established the Chandler family ownership of the Times, which continued to lean to the right until the social turmoil of the 1960s (Goldstein, 2009; McDougal, 2002). In the years during and after World War II, ideological conservatives established numerous outlets in an effort to influence public opinion and policy, including the Christian Nationalist The Cross and the Flag starting in 1942, Human Events in 1944, William F. Buckley’s National Review in 1955, and the anticommunist Dan Smoot Report in 1957, and others (Hemmer, 2016; Nash, 1976). In more recent years, syndicated talk radio benefited from the demise of the longstanding Fairness Doctrine, which previously required equal treatment of opposing political viewpoints on public airways. The Federal Communications Commission abolished the doctrine in 1987; Rush Limbaugh’s radio show debuted in 1988 (Berry & Sobieraj, 2011; Editors of Encyclopaedia Brittanica, 2021). But Limbaugh was not even close to being the first influential conservative voice on radio. He was preceded half a century earlier by Catholic priest, Father Charles Coughlin, who railed against communism and unions, and for Wall Street and capitalism, to his 90 million listeners (Krebs, 1979; Vultee, 2023).

The widespread dissemination of cable television and commensurate popularity of CNN in the early 1980s set the stage for ideological cable news outlets. Rupert Murdoch’s Fox News Channel launched in October, 1996, grew steadily to reach 17% of the U.S. audience by 2000, and became the top-rated cable news outlet in January of 2002, surpassing CNN (DellaVigna & Kaplan, 2007). As Fox News disseminated into new media markets, it was linked with an increase in Republican voter participation and GOP candidate success in those markets (DellaVigna & Kaplan, 2007). Fox remained the top-rated cable news source for 19 years, falling again, to CNN in 2021; CNN, ironically, was aided by two new more conservative upstarts chipping away at Fox’s viewership: NewsMax and One America News Network (Beer, 2021).

Local News

After a period of partisan ownership from the founding of the United States through the Civil War, local media migrated away from partisan portrayals to more objective reporting through the 20th Century (Schweikart, 2014). That began to change over the last decade, again due to federal regulatory changes – this time, about media ownership. Aggregation of newspapers began in earnest in the 1970s and has accelerated dramatically in the last decade, with Gannett/Gatehouse now owning about 260 papers (Kaufhold, 2020; Pickard, 2018). FCC policy changed in 2017 to allow greater aggregation, including – for the first time – the ownership of newspapers and televisions in the same market (Shepardson, 2019). While aggregation did predict an increase in identical content across news outlets in an owner’s portfolio, in most cases it was objective or nonpolitical content (Kaufhold, 2020). But one television station group owner, Sinclair Broadcasting, disseminated partisan messages across dozens – perhaps more than 100 – local television newscasts from coast to coast. One, a conservative opinion script which warned viewers to not trust fake news – presumably, news outlets not owned by Sinclair (Fortin & Bromwich, 2018) received a lot of attention. At the time, Sinclair owned 193 local television stations – most of which broadcast local news. Sinclair’s portfolio of stations at that time, April of 2018, reached 40% of American households (Matthews, 2018).

Community Journalism

Reader (2012) argues that community journalism is defined as the relationship between journalists and the communities they report on. That civic connection runs through local newspapers and local television and radio, and local journalists have reported feeling a greater responsibility to serve their geographic community than those at larger news outlets (Reader, 2012). Local news, even in daily news outlets, has been linked with increased community involvement by those who consume that news (Lowery, 2008; Reader, 2012). Local newspapers have been shown to foster community building, which can create social capital and increase citizen agency in important community decisions (Nicodemus, 2004). Local news outlets have also been shown to increase accountability for local leaders, foster community by better connecting consumers to where they live, and often serve as the primary source for local information (Radcliffe & Ali, 2018).

Local Newspapers

and Local Television News

Local newspapers have long been established as leaders in providing audiences with local information and accountability (McCombs & Funk, 2011). Local papers have been associated with residents being more informed about their communities, but local television has been shown to be a better source to generate interest in local politics (McLeod, et al., 1996; Yanich, 2016). Also, intermedia agenda setting has, for decades, woven the same news stories throughout the fabric of a local news landscape as local television news outlets mimic coverage in their local papers, and vice versa (Dearing & Rogers, 1996; McCombs & Funk, 2011). Covering local stories has also been shown to be good for business, increasing the perceived value of a news outlet among residents, especially in local TV (Yanich, 2016). Distinctions between local newspapers and television news sources exist but, as far as story selection, they are often more alike than dissimilar.

Immigration

Immigration is increasingly appearing as a contentious political topic among local lawmakers. State legislatures passed 90 percent more immigration bills in 2017 than in the year before (Felter, Renwick & Cheatham, 2020). California lawmakers passed a law allowing state identification cards, including California driver’s licenses, for undocumented immigrants – the latest in a years-long push to decriminalize undocumented migration in the Golden State (Eagly, 2017; Enriquez, Vera & Ramakrishnan, 2019). Texas lawmakers took the opposite tack, passing a law against “sanctuary cities” in 2017 and, in some years, leading the nation in generating subfederal, or state-level, immigration policies (Butz & Kehrberg, 2019; Matos, 2017). Arizona was found to have the most restrictive state-level immigration policies; California, the least. Ohio fell in-between (Wills & Commins, 2018).

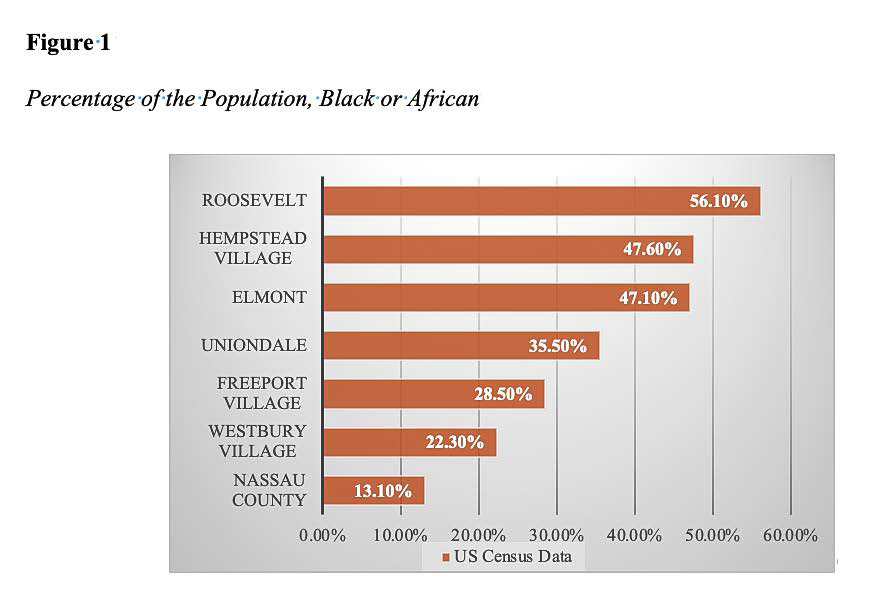

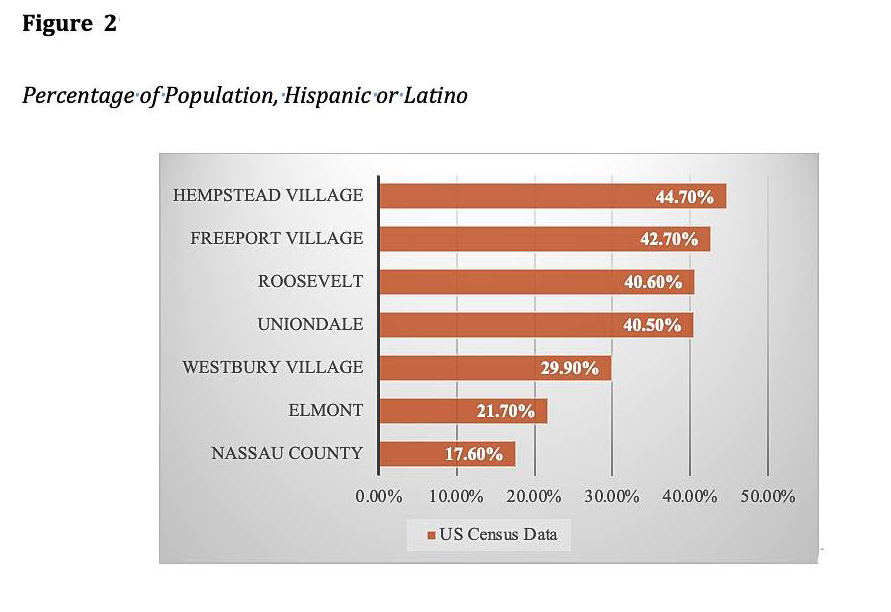

News sources headquartered in states along the southern border have been shown to have two differences from more distant states: First, they’re more likely to cover the border; second, they tend to be more nuanced or supportive of immigration than states in the Midwest or South. (Branton & Dunaway, 2009). Consequently, public opinion among border-state residents has been found to be more accepting, or at least open-minded, when it comes to immigration (Dunaway, Branton, & Abrajano, 2010). With that in mind, the present study surveyed residents from two states in an effort to capture not only the differences of consuming national versus local media, but to identify whether there were distinctions between local media in different areas of the country. Texas leans conservative and shares the longest border with Mexico of any state – 1,254 miles; Ohio has been highly predictive in Presidential elections for decades, which makes it the ultimate predictive swing state.

The demographics of Texas and Ohio are also substantially different, especially concerning the number of Hispanics in each. Texas has the third-largest proportion of Hispanics in the country (39.1%; Census, 2018) and ranks second by actual population numbers. Ohio is home to fewer than one-tenth as many Hispanics, at 3.7% of the state’s population (Census, 2019). Texas also has a substantially more undocumented immigrants: 6.1% of the population, versus Ohio’s 0.8% (Pew Research Center, 2016).

Immigration attitudes and media habits are a well-established area of scholarship and studies have found a significant effect from consuming partisan media (Price & Kaufhold, 2019). Much contemporary research on media consumption and attitudes on contentious political issues, like immigration, focus on the effects of selective exposure to partisan media (Stroud, 2007; Garrett, Carnahan & Lynch, 2013). But the effect of local media consumption on partisan flashpoints, like immigration, hasn’t been as well studied, despite research showing that local and national media cover immigration differently, especially in border states (Branton & Dunaway, 2009; Dunaway, Branton, & Abrajano, 2010). This study examines the following research questions:

RQ1: How will local newspaper consumption relate to attitudes on immigration?

RQ2: How will local television news consumption relate to attitudes on immigration?

Conservative Cynicism

Conservatives – and to a lesser extent, progressives – have been shown to be distrustful of science and academia. A substantial longitudinal study found trust in science was stable for the last quarter of the 20th Century except among conservatives, whose trust in science faded from higher than progressives in 1975 to much lower by 2010 (Gauchat, 2012). The only other predictive independent variable was level of religious belief, which also predicted the same decline in trust in science (Gauchat, 2012). Religious belief and trust in science were also shown to be inversely related, with a belief that scientists’ perceived atheism made them a potential threat to those with religious beliefs (Simpson & Rios, 2019).

Message exposure matters, though. Partisans (both sides) express distrust of a science message after exposure to a media message with which they disagree; for example, anthropogenic global warming among conservatives or hydraulic fracturing (fracking) for natural gas extraction among progressives, although conservatives were shown to be more reactive (Nisbet, Cooper & Garrett, 2015). The source of a message has also been shown to influence partisan resistance to or support of a message. Exhortations for social distancing during the COVID-19 pandemic were generally more palatable to those on the left but were made more palatable if the appeal to social distance came from a Republican source (Koetke, Schumann & Porter, 2021).

This distrust in science and, more so, in scientists, is increasingly reflected in public opinion polling since 2016 (Matthews, 2020). Fairly suddenly, poll results began over-predicting support for Democrats, and even adjustments for the 2018 and 2020 midterm and presidential elections didn’t correct what appears to be a reluctance by conservatives to participate in polling (Cohn, 2022; Ekins, 2020; Matthews, 2020). The possible implications here of this conservative reticence to respond to online surveys is discussed later in this study.

Conservatives also express distrust of legacy news outlets, especially those which lead intermedia agenda setting, the New York Times and Washington Post. Not only conservatives perceive that those newspapers lean left. Hawdon, et al. (2020) found, for example, that participants in their study reported CNN showed 57% more liberal polarization than a neutral position; Fox News was one-fifth as likely to show that lean to the left. But both the Washington Post and New York Times were perceived as being significantly liberally polarized. Consequently, conservative news consumers report being highly unlikely to trust and consume news from those two papers while showing strong favoritism for Fox News (Hawdon, et al., 2020; Price & Kaufhold, 2019). Based on this literature, the study will also examine the following research question:

RQ3: How will party identity relate to news consumption and attitudes on immigration?

Methods

A panel survey was executed online in the spring of 2018, opening March 26 and closing April 11; it captured valid responses from 638 participants. Respondents were represented about equally between the Ohio (N=322) and Texas (N=316). Respondents were presented with three matrix questions, two of which included topics around immigration which are detailed below. The third matrix used a 5-point scale to measure consumption (1 = Rarely/Never, 5 = Often) of 28 news sources (New York Times, Washington Post, Chicago Tribune, Los Angeles Times, Wall Street Journal, CNN. MSNBC, Fox News Channel, ABC, CBS, NBC, NPR, PBS, local TV news, news radio, talk radio, Huffington Post, Drudge Report, Daily Kos, Breitbart, other; and, in Ohio, Cincinnati Enquirer, Cleveland Plain Dealer, Columbus Dispatch; and in Texas, Dallas Morning News, Houston Chronicle and San Antonio Express News). The local papers were all selected because they were the three largest-circulation papers in each respective state, and served the three largest population centers in each state: Cincinnati Enquirer, Cleveland Plain Dealer, Columbus Dispatch, Dallas Morning News, Houston Chronicle, and San Antonio Express News.

In order to quantify the level of polarization on immigration issues, survey respondents were asked to select their support for a number of immigration-related topics on a 5-point Likert-type scale (1 = Not at all supportive; 5 = Very supportive). The 11 items in the matrix question were all drawn from contemporary news coverage to make them even more salient to the study of media choice and attitudes. They were: 1) Building a border wall along the U.S.-Mexico border; 2) DACA or Delayed Action for Childhood Arrivals; 3) Pathway for citizenship for Delayed Action for Childhood Arrivals; 4) Sanctuary cities; 5) Immigrant detention centers; 6) Deportation arrests at courthouses by immigration agents; 7) Raids at workplaces by immigration agents; 8) Fines for U.S. businesses that hire undocumented workers; 9) Increased deportations of undocumented immigrants; 10) Birthright citizenship; and 11) Increased border surveillance. A second matrix asked respondents to rate support for seven general immigration issues, and two specific to Syrian/Muslim immigrants, including: 1) Merit-based immigration; 2) Family reunification (“chain migration”); 3) Extreme vetting; 4) Temporary work visas (“guest workers”); 5) Temporary protected status for work; 6) Temporary protected status due to environmental disaster or ongoing armed conflict in a home country; 7) Diversity visa lottery system; 8) Trump administration travel ban from seven predominately Muslim countries; 9) Syrian refugees resettlement. A 5-point Likert-type scale (1 = Not at all supportive. 5 = Very supportive) asked how supportive respondents were of immigration from Europe, Africa, Asia, the Middle East, and Mexico/Latin America.

Texans in the survey were younger, more male, and had higher incomes (see Table 1) and levels of education than Ohioans. Respondents in both states leaned more toward the Democratic party, but Texans were significantly more likely than Ohioans to identify as Independent or Republican. U.S. Census data shows that Ohio’s population is 51% female; 12.9% black; 3.8% Hispanic Median household income is $52,407. Texas’s population is 50.3% female; 12.7% black; 39.4% Hispanic, and median household income is $57,051 (Census, 2018).

Table 1

Participants in 2016 CCES survey and 2018 Ohio/Texas survey

2018 2-state panel survey (Ohio, n=322; Texas, n=316)

|

2018 2-State survey |

||

|

Item |

Ohio |

Texas |

|

Average Age * |

46.8 |

40.7 |

|

Gender (Female)*** |

51.6% |

51.9% |

|

White*** |

82.6% |

79.7% |

|

Black*** |

12.7% |

13.0% |

|

Hispanic*** |

4.0% |

21.6% |

|

Asian** |

2.2% |

0.9% |

|

Middle Eastern |

0.3% |

0.3% |

|

Native American |

1.2% |

0.9% |

|

Mixed |

0.3% |

1.9% |

|

Other |

0.6% |

3.2% |

|

Democrat* |

35.7% |

33.2% |

|

Independent |

33.9% |

32.9% |

|

Republican** |

26.1% |

31.6% |

|

Education Mean (3=Some College; 4=2-year degree) |

2.93 |

2.91 |

|

Household income Mean (5=$40,000-$49,999) |

4.88 |

5.03 |

*** p=</001; ** p=<.01; * p=<.05; + p=<.10

Four conservative outlets emerged from Varimax component matrix factor analysis (Fox News, conservative talk radio, Drudge Report, Breitbart). These were scaled into a single Conservative Media variable (Cronbach’s =.736). National Public Radio (NPR) emerged with three openly liberal media outlets to form a Liberal Media variable (NPR, Daily Kos, MSNBC and Huffington Post; Cronbach’s =.803).

From the 2-state survey, two immigration scales were crafted to test partisan media use and attitudes on immigration. Varimax component matrix factor analysis identified 13 items which loaded high, all opposed to immigration (building a border wall; immigrant detention centers; deportation arrests at courthouses; raids at workplaces; fines for U.S. business which hire undocumented workers; increased deportations; increased border surveillance; the Trump Administration travel ban; immigrants are a burden on the country because they take our jobs, housing and health care; America is too open to people from all over the world; undocumented immigrants commit more crimes than American citizens; immigration increases America’s risk of a terrorist attack; and controlling and reducing illegal immigration is an important foreign policy tool). An Immigration Negative measure crafted from these items showed exceptionally high reliability (Cronbach’s =.950).

An Immigration Positive scale was crafted in the same way. Fourteen items (DACA; pathway to citizenship; sanctuary cities; birthright citizenship; family reunification/chain migration; temporary protected status due to natural or manmade disaster; sympathetic to undocumented immigrants; supportive of immigration from Africa, Asia, Middle East, Mexico/Latin America; America’s openness to people from all over the world is essential to who we are as a people; the U.S. government should make it possible for illegal immigrants to become U.S. citizens; and the number of people allowed to legally move to the U.S. should be increased) Positive toward immigration showed good reliability (Cronbach’s =.931).

Results

Geography clearly plays a role in audience attitudes about immigration. Reading Texas newspapers, despite – or perhaps because of – the state’s substantial border with Mexico didn’t significantly influence attitudes about immigration. Respondents reading national newspapers or watching partisan cable television news behaved in predictable ways, based on previous scholarship. And the effect wasn’t nearly as strong as the national news outlets – for example, reading Ohio newspapers didn’t relate to a negative relationship with support for immigration; only a significant relationship with opposition to immigration.

Regression analysis examined two scaled dependent variables: Support for immigration, based on 14 items in the Immigration Positive Scale; and opposition to immigration, comprised of 13 items against it. Independent variables were scales of different types of media consumption – especially readers of local newspapers in Ohio or Texas, but also partisan news consumers in each state (four items each comprising Conservative or Liberal news).

Living near the border in Texas, surrounded by a significant Hispanic population, seemed to soften the effect of conservative media consumption (see Table 2). Ohio conservatives (consumers of Conservative Media) were a little more opposed to immigration (Immigration Negative) than Texas conservatives; but Ohio liberals (consumers of Liberal Media) were also a little more supportive of immigration than Texas liberals. All the relationships yielded significant differences. Reading Ohio newspapers, or watching conservative cable TV news, predicted significant negative support for, or opposition to, immigration. Reading Texas newspapers didn’t relate significantly to support for or opposition to immigration; but reading Ohio newspapers does significantly predict opposition to immigration (Table 3).

Table 2

Linear Regression, Conservative/Liberal media, Immigration Positive/Negative, by state

|

Immigration positive+ |

B |

SE |

Adjusted R2 |

p-value |

|

Ohio Cons Media |

.280 |

.052 |

.177 |

.00 |

|

Texas Cons Media |

.256 |

.048 |

.220 |

.00 |

|

Ohio Liberal Media |

.523 |

.053 |

.230 |

.00 |

|

Texas Liberal Media |

.515 |

.052 |

.256 |

.00 |

|

Immigration negative- |

B |

SE |

Adjusted R2 |

p-value |

|

Ohio Cons Media |

.368 |

.046 |

.177 |

.00 |

|

Texas Cons Media |

.365 |

.041 |

.220 |

.00 |

|

Ohio Liberal Media |

.199 |

.046 |

.230 |

.00 |

|

Texas Liberal Media |

.258 |

.045 |

.256 |

.00 |

Reading national newspapers, in both Ohio and Texas, predicted significantly more support for immigration, as did watching evening national broadcast TV news. (see Table 3).

Table 3

Linear Regression, Local versus National News Outlets, Immigration Positive/Negative

|

Immigration pos+ |

B |

SE |

Adjusted R2 |

p-value |

|

Ohio newspapers |

.026 |

.073 |

.190 |

.72 |

|

National newspapers |

.387 |

.069 |

.00 |

|

Immigration pos+ |

B |

SE |

Adjusted R2 |

p-value |

|

Texas newspapers |

.035 |

.075 |

.155 |

.64 |

|

National newspapers |

.303 |

.070 |

.00 |

|

Immigration neg- |

B |

SE |

Adjusted R2 |

p-value |

|

Ohio newspapers |

.187 |

.092 |

.009 |

.04 |

|

National newspapers |

-.078 |

.087 |

.37 |

|

Immigration neg- |

B |

SE |

Adjusted R2 |

p-value |

|

Texas newspapers |

.128 |

.094 |

.015 |

.80 |

|

National newspapers |

..022 |

.088 |

.17 |

|

Immigration pos+ |

B |

SE |

Adjusted R2 |

p-value |

|

Local TV news |

-.018 |

.034 |

.051 |

.60 |

|

National TV news |

.176 |

.046 |

.00 |

|

|

Conservative cable |

.051 |

.062 |

.41 |

|

Immigration neg- |

B |

SE |

Adjusted R2 |

p-value |

|

Local TV news |

-.016 |

.037 |

.105 |

.67 |

|

National TV news |

-.053 |

.051 |

.30 |

|

|

Conservative cable |

.429 |

.069 |

.00 |

The Conservative and Liberal media scales are also predictive of support for, or opposition to, immigration and in predictable ways. Conservative media consumption (Fox News, conservative talk radio, Drudge Report, Breitbart) significantly predicted less support for immigration; more opposition to it. This was, as expected, a mirror image of consuming liberal media (NPR, Daily Kos, MSNBC and Huffington Post) which predicted significantly more support for immigration.

Discussion

Local media consumption was partially predictive of attitudes about immigration: reading local newspapers in Ohio was linked with significantly more negative attitudes about immigration; there was no local newspaper effect in Texas. Reading national newspapers was predictive of significantly more positive attitudes about immigration. The local newspaper finding in Ohio may be an artifact of an intervening variable; for example, data from Pew (Shearer, 2018) and others has robustly shown that newspapers are increasingly read by older Americans, and older Americans – especially whites – have been shown to be less receptive to immigration. These are also the demographic members most likely to be in the audience for conservative media, such as Fox News Channel. At the same time, the average age of a television news viewer is now over 60 and climbing by the year (Shafer, 2024). Ohioans average about five years older than Texans, in both Census data and this sample, which may also independently predict less support for immigration.

The pedigree and editorial slant of each newspaper may also play a role. The Cleveland Plain Dealer has a turbulent ideological history, starting in the 1840s and, for a brief period, becoming an outpost of Confederate opinion in a Union state (Encyclopedia of Cleveland History, n.d.). From 1940 onward, though, the Plain Dealer endorsed the Republican candidate in every presidential election except two: Lyndon Johnson in 1964, in the wake of the Kennedy assassination; and Bill Clinton’s youthful run in 1992. The Columbus Dispatch also has a history of leaning right editorially. Editors endorsed Secretary Hillary Clinton over Donald Trump in 2016 but had previously endorsed every Republican candidate for president going back a century (Anderson, 2004; Tate, 2016). Obviously, the substantial Hispanic population of Texas – more than five times higher than in Ohio, per capita – may have an outsized influence. With exposure comes empathy.

The local newspaper finding is a bit of a surprise. Local newspapers have long been shown to be more thorough and credible than local television news (Maier, 2010). Also, as noted earlier, some local television station owners’ groups have been linked with more ideological, conservative-leaning valence with their news presentation, presumably in a way that would be less supportive of immigration (Hedding, Miller, Abdenour & Blankenship, 2019). To use Sinclair as an example, the company recently owned 11 television stations in Ohio and 23 across Texas (Bryan, 2018). Yet, the presence of those stations showed no significant relationship for or against immigration. Likewise, the Cincinnati Enquirer editorial board also endorsed the Republican candidate for president in every single presidential election from 1920 until it endorsed Hillary Clinton in 2016 (Bhatia, 2016). Clearly, the political legacy of these top three Ohio newspapers may attract more right-leaning readers. These papers may also play a role in intermedia agenda setting, influencing what appears in local television newscasts.

Local news – newspaper and television – is also likely to be more reflective of local political sentiments than national media (McCombs & Funk, 2011; Yanich, 2016). Local news consumption didn’t predict widespread changes in immigration attitudes, but it may be important to understand that local news may serve as an alternative pathway to the well-established role of national newspapers and partisan cable news in opinion formation.

The intervening role of geography also clearly plays a role. Were Ohio newspapers more likely than their Texas counterparts to cover immigration in an “Ohio way” – less supportive of immigration than those living much closer to the border and with a substantially larger Hispanic population? Or does it only reflect what polling data shows – less support for immigration among Ohioans than Texans, which reveals itself in the newspaper audience?

Is local news community journalism? One could argue, in an era of hedge-fund and aggregate ownership, that it isn’t – but respondents in this study viewed it that way, as indicated by their different perspectives on immigration, predicted by local vs. other news sources. Consumers of Ohio local media viewed immigration more negatively than did consumers of Texas local media. In both states, local news consumers viewed immigration more sympathetically than those who reported being more likely to consumer conservative national media, like Fox News Channel. Getting news from a local source, whether near the border or not, yielded more tolerance for immigration than did consumption of conservative news outlets; and even more so in Texas, near the border. Diverse news consumption is shown here, as in previous scholarship, to moderate views on contentious issues like immigration but the findings here support the important role of local media sources to be part of that conversation.

A final consideration is that Texas is now home to an enormous diaspora of people from other places, drawn to the Lone Star State by rapid expansion of the job market in the decade after the Great Recession. This influx of new “Texans,” including nearly 9,000 Ohioans who moved to Texas in 2019 alone (Census, 2019), couldn’t help but be exposed to a ubiquitous Hispanic population in the U.S.’s largest border state. Migrants who left the Buckeye State also reported higher incomes than those who remained (Hanauer, 2019). Ohio, by comparison, was much slower to recover, saw falling incomes and home prices, and suffered a net out-migration after the Great Recession (Hanauer, 2019). Ohio ranked sixth among all states for out-migration in 2018, up from seventh the year before and continuing a pattern dating to the recession in 2008 (Merritt, 2019). The search for employment was cited by 60.75% of those leaving Ohio, and those under 35 were most likely to leave.

This economic malaise may inform political inclinations much differently in Ohio than Texas. For example, after 20 years as a closely divided swing state (Bill Clinton won Ohio by 6% in 1996; every subsequent election through 2012 was closer), Ohio twice went for Republican Donald Trump by 8-point margins (FEC, 2020). Trump, obviously ran aggressively against immigration and instituted provocative policies like criminalizing undocumented immigration, leading to the separation of migrant children from their parents. Ohioans seemed more supportive of that immigration position than Texans, as told by Trumps’ vote margins.

Local News

There will be assertions that “local news” isn’t the same thing as “community journalism” which is understandable but, in this case, that assertion is misguided. Earlier literature establishes the important role of local news in community building, including informing and linking neighbors, informing them, and contributing to the development of social capital. Also, the outlets most often thought of as community journalism – small hyper-local weeklies – serve an essential role in their communities but are less likely to be able to invest time and money in covering a national issue like immigration – especially in a non-border state like Ohio. Finally, compared to partisan cable news outlets, like Fox News Channel and MSNBC, local television and newspaper newsrooms were shown here to make have a unique and valuable contribution to attitudes about this contentious issue.

This study captures an effect of local news consumption which is worthy of future study. Subsequent research should consider adding content analysis of local media in the comparative states and continue to drill down in a survey into voter attitudes about immigration policies and issues. This study administered the survey during the midterm election season. Administering it during a presidential election year would be much more likely to capture McCombs and Shaw’s (1972) “need for orientation” which would probably yield more stark relationships. Undecided voters who intended to vote in the highly contested 2016 and 2020 campaigns would likely have felt more strongly about the issue of immigration, increasing the likelihood of us capturing significant differences by media use and geographic location.

There would also be value to considering a third or even a fourth state of different ideology and demographic makeup – perhaps a much smaller border state, like New Mexico; or a Midwestern state with a significant Hispanic population, like Illinois. That diversity of respondents would likely offer some nuance to issue of immigration.

Also, the well-documented bias by conservatives against participating in survey research, and distrust of scientists and their motives, may have reduced their representation in this sample. This data was collected well into the window of conservative survey resistance which began, abruptly, in 2016. The topic of study here is controversial. It was, and still is, the central issue of consecutive presidential campaigns. In addition, this IRB-approved study was distributed with clear labeling that it was from an academic institution. Any, or all, of these factors could be expected to trigger conservative resistance to participation. There is evidence, based on the frequencies in both states showing party identification (Table 1, p. 10) suggesting that Republicans were underrepresented in this survey sample, although voter registration data from the Ohio Secretary of State in 2021 showed 11% more Democrats than Republicans (OhioSOS, 2021); Gallup data showed, in 2017 (the year before this survey), Texas registrations showed the state was 41% Republican, 38% Democrat (Gallup, 2017). Ohio respondents in this sample align nicely with state registrations but the data from Texas suggests an undercount of Republicans – perhaps due to conservative resistance to surveys and scientists. This could have minimized the effect of local news consumption by conservatives in Texas in this data.

Finally, this study chose immigration because it was a central issue to the current political milieu but scholars targeting these relationships in the future should design a study around the issue du jour of that contemporary political campaign. Regardless, the role of local media in opinion formation on national issues isn’t adequately studied and this scholarship found some small but important role in that relationship with Ohio newspapers. Media scholars and practitioners would both be well served by having a better understanding of that relationship.

References

- Anderson, K. (2004, October 26). Papers back Kerry – but does that help? BBC News. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/americas/3953227.stm

- Beer, T. (2021). Fox News Viewership Plummets: First Time Behind CNN And MSNBC In Two Decades. Forbes, January 16, 2021. https://www.forbes.com/sites/tommybeer/2021/01/16/fox-news-viewership-plummets-first-time-behind-cnn-and-msnbc-in-two-decades/?sh=2b91ae2b5342

- Berry, J. M. & Sobieraj, S. (2011). Understanding the Rise of Talk Radio. PS: Political Science & Politics, 44(4), 762-767. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096511001223

- Bhatia, P. (2016, September 23). Why we’re endorsing for president. Cincinnati.com. https://www.cincinnati.com/story/opinion/columnists/2016/09/23/why-were-endorsing-president/90832776/.

- Branton, R., & Dunaway, J. (2009). Spatial proximity to the U.S.-Mexico border and

- newspaper coverage of immigration issues. Political Research Quarterly, 62(2), 289-302. https://doi.org/10.1177/1065912908319252

- Bryan, B. (2018). Sinclair Broadcast Group owns local news stations across the US — find out whether your local station is one of them. Business Insider, April 3, 2018. https://www.businessinsider.com/sinclair-broadcast-group-stations-by-state-list-2018-4

- Butz, A. M. & Kehrberg, J. E. (2019). Anti‐Immigrant Sentiment and the Adoption of State Immigration Policy. Policy Studies Journal, 47(3), 605-623. https://doi.org/10.1111/psj.12326

- Census (2018). QuickFacts Ohio; United States. U.S. Census Bureau, accessed online

- March 29, 2019. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/oh,US/SEX255217

- Census (2019). Sta5te-to-State Migration Flows: 2019. Dataset downloaded March 28, 2021. https://www2.census.gov/programs-surveys/demo/tables/geographic-mobility/2019/state-to-state-migration/State_to_State_Migrations_Table_2019.xls

- Cohn, N. (2022, November 8). Are the Polls Still Missing ‘Hidden’ Republicans? Here’s What We’re Doing to Find Out. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/11/08/upshot/poll-experiment-wisconsin-trump.html

- Corasaniti, N. (2016, August 31). A Look at Trump’s Immigration Plan, Then and Now.

- The New York Times. Retrieved on June 24, 2018, from https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2016/08/31/us/politics/donald-trump-immigration-changes.html

- Cornelius, W. A. (1981). The Reagan Administration’s Proposals for a New U.S. Immigration Policy: An Assessment of Potential Effects. International Migration Review, 15(4), 769-778. https://doi.org/10.1177/019791838101500410

- Dahlgren, P. M., Shehata, A. & Strömbäck, J. (2019). Reinforcing spirals at work? Mutual influences between selective news exposure and ideological leaning. European Journal of Communication, 34(2), 159-174. https://doi.org/10.1177/0267323119830056

- Dearing, J. & Rogers, E. (1996). Agenda Setting. Sage.

- DellaVigna, S. & Kaplan, E. (2007). The Fox News Effect: Media Bias and Voting. The Quarterly Journal of Media Economics, 122(3), 1187-1234. https://doi.org/10.1162/qjec.122.3.1187

- Despart, Z. & Melhado, W. (2024, February 29). As Biden and Trump visit the border, many Texas residents feel ignored. Texas Tribune.

- https://www.texastribune.org/2024/02/29/texas-border-eagle-pass-brownsville-trump-biden/

- Dunaway, J., Branton, R., & Abrajano, M. (2010). Agenda setting, public opinion, and

- the issue of immigration reform. Social Science Quarterly, 91(2), 359-378.

- https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6237.2010.00697.x

- Eagly, I. V. (2017). Criminal Justice in an Era of Mass Deportation: Reforms from California. New Criminal Law Review, 20(1), 12-38. https://doi.org/10.1525/nclr.2017.20.1.12

- Editors of Encyclopaedia Brittanica (2021). Rush Limbaugh. Encyclopaedia Brittanica, updated February 17, 2021. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Rush-Limbaugh

- Ekins, E. (2020, March 2). Why Did Republicans Outperform The Polls Again? Two Theories. FiveThirtyEight blog. https://fivethirtyeight.com/features/why-did-republicans-outperform-the-polls-again-two-theories/

- Encyclopedia of Cleveland History (n.d.). PLAIN DEALER. https://case.edu/ech/articles/p/plain-dealer

- Enriquez, L. E., Vera, D. V. & Ramakrishnan, S. K. (2019). Driver’s Licenses for All? Racialized Illegality and the Implementation of Progressive Immigration Policy in California. Law & Policy, 41(1), 34-58. https://doi.org/10.1111/lapo.12121

- FEC (2020). Election and Voting Information. Federal Election Commission. https://www.fec.gov/introduction-campaign-finance/election-and-voting-information/

- Felter, C., Renwick, D. & Cheatham, A. (2020). The U.S. Immigration Debate. Council on Foreign Relations. https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/us-immigration-debate-0

- Fortin, J. & Engel Bromwich, J. (2018). Sinclair Made Dozens of Local News Anchors Recite the Same Script. New York Times, April 2, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/04/02/business/media/sinclair-news-anchors-script.html

- Gallup (2017). 2017 Party Affiliatuion by State. Ohio Secretary of State. https://news.gallup.com/poll/226643/2017-party-affiliation-state.aspx

- Gamboa, S., Shabad, R. & Gregorian, D. (2021). Democrats, Republicans hold dueling border trips. Their takeaways couldn’t be more different. NBC News, March 28, 2021. https://www.nbcnews.com/politics/congress/democrats-republicans-stage-dueling-trips-u-s-mexico-border-n1262144

- Garrett, R. K., Carnahan, D. & Lynch, E. K. (2013). A Turn Toward Avoidance?

- Selective Exposure to “Online Political Information, 2004-2008. Political

- Behavior, 35(1), 113-134. https://doi-org.libproxy.txstate.edu/10.1007/s11109-011-9185-6

- Gauchat, G. (2012). Politicization of Science in the Public Sphere: A Study of Public Trust in the United States, 1974 to 2010. American Sociological Review, 77(2), 167-187. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23102567

- Goldstein, P. (2009, January 27). L.A.’s Original Family Dynasty. Los Angeles Times. https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-2009-jan-27-et-bigpicture27-story.html

- Hanauer, A. (2019). Ohio’s Economy No Longer Fully Recovers after Recessions. Economic Policy Institute, May 23, 2019. https://www.epi.org/blog/ohios-economy-no-longer-fully-recovers-after-recessions/

- Hawdon, J., Ranganathan, S., Leman, S., Bookhultz, S., Mitra, T. (2020). Social Media Use, Political Polarization, and Social Capital: Is Social Media Tearing the U.S. Apart?. In Gbriele Meiselwitz, (Ed), Social Computing and Social Media. Design, Ethics, User Behavior, and Social Network Analysis. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-49570-1_17

- Hedding, K. J., Miller, K. C., Abdenour, J. & Blankenship, J. C. (2019). The Sinclair Effect: Comparing Ownership Influences on Bias in Local TV News Content. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 63,(3), 474-493. https://doi.org/10.1080/08838151.2019.1653103

- Hemmer. N. (2016). The Outsiders, in Nicole Hemmer (Ed.) Messengers of the Right: Conservative Media and the Transformation of American Politics, 28-48. University of Pennsylvania Press. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1dt00xq.5

- Jahng, M. R. (2018). From reading comments to seeking news: exposure to disagreements from online comments and the need for opinion-challenging news. Journal of Information Technology & Poltics, 15(2), 142-154. https://doi.org/10.1080/19331681.2018.1449702

- Kaufhold, K. (2020). News and Information Industry. In Meghan Mahoney and Tang Tang (Eds.) Handbook of Media Management and Business, 243-263, Rowman & Littlefield.

- Kellstedt, P. (2003). The mass media and the dynamics of American racial attitudes. New

- York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Koetke, J., Schumann, K. & Porter, T (2021). Trust in science increases conservative support for social distancing. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 24(4), 680-697. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430220985918

- Krebs, A. (1979, October 28). Charles Coughlin, 30’s ‘Radio Priest.’ New York Times.

- Lowery, Brozana & Mackay (2008). Toward a Measure of Community Journalism. Mass Communication and Society, 111(3), 275-299. https://doi.org/10.1080/15205430701668105

- Maier, S. (2010). All the News Fit to Post? Comparing News Content on the Web to Newspapers, Television, and Radio. Newspaper Research Journal, 87(304), 548-562. https://doi.org/10.1177/107769901008700307

- Matos, Y. (2017). Geographies of Exclusion: The Importance of Racial Legacies in Examining State-Level Immigration Laws. American Behavioral Scientist, 61(8), 808-831. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764217720480

- Matthews, D. (2018). Sinclair, the pro-Trump, conservative company taking over local news, explained. Vox.com, April 3, 2018. https://www.vox.com/2018/4/3/17180020/sinclair-broadcast-group-conservative-trump-david-smith-local-news-tv-affiliate

- Matthews, D. (2020, November 10). One pollster’s explanation for why the polls got it wrong. Vox. https://www.vox.com/policy-and-politics/2020/11/10/21551766/election-polls-results-wrong-david-shor

- McCombs, M. E. & Funk, M. (2011). Shaping the Agenda of Local Daily Newspapers: A Methodology Merging the Agenda Setting and Community Structure Perspectives. Mass Communication and Society, 14(6), 905-919. https://doi.org/10.1080/15205436.2011.615447

- McLeod, J. M., Daily, K., Guo, Z., Eveland, Jr., W. P., Bayer, J., Yang. S. & Wang. H. (1996). Community integration, local media use and democratic processes. Communication Research, 23(2), 179-209. https://doi.org/10.1177/009365096023002002

- McCombs, M. E. & Shaw, D. L. (1972). The Agenda-Setting Function of Mass Media. The Public Opinion Quarterly, 36(2), 176-187. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2747787

- McDougal, D. (2003). Privileged Son: Otis Chandler and the Rise of and Fall of the L.A.Times Dynasty. Cambridge:Perseus Publishing.

- Merritt, J. (2019). Ohio Ranks No. 6 On List Of Most Moved-From States In 2018. WVXU.org Cincinnati Public Radio, January 2, 2019. https://www.wvxu.org/post/ohio-ranks-no-6-list-most-moved-states-2018#stream/0

- Miroff, N. & Sacchetti, M. (2021). Family groups crossing border in soaring numbers point to next phase of crisis. New York Times, March 28, 2021. https://www.washingtonpost.com/national/migrant-families-border/2021/03/28/355c59a2-8d70-11eb-aff6-4f720ca2d479_story.html

- Nasaw, D. (2001). The Chief: The Life of William Randolph Hearst. Boston:Houghton Mifflin.

- Nash, G. H. (1976). The Conservative Intellectual Movement in America Since 1945, 186-193. Wilmington, DE:ISI Books.

- NBC News (2016). New Hampshire Primary Results. Published February 9, 2016 https://www.nbcnews.com/politics/2016-election/primaries/nh/

- Newport, F. (2015, July 20). American Public Opinion and Immigration. Gallup.

- Retrieved from http://news.gallup.com/opinion/polling-matters/184262/american-public-opinion-immigration.aspx

- New York Times (2016). Iowa Caucus Results. Published February 1, 2016. https://www.nytimes.com/elections/2016/results/primaries/iowa

- Nicodemus, D. M. (2004). Mobilizing Information: Local News and the

- Formation of a Viable Political Community. Political Communication, 21, 161-176. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584600490443868

- Nisbett, E. C., Cooper, K. E. & Garrett, R. K. (2015). The Partisan Brain: How Dissonant Science Messages Lead Conservatives and Liberals to (Dis)Trust Science. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 658(1), 36-66. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716214555474

- OhioSOS (2021, October 1). Secretary of state provides update on party affiliation data. https://www.ohiosos.gov/media-center/press-releases/2021/2021-10-01-a/

- Pew (2016). Top voting issues in 2016 election. Pew Research Center U.S. Politics and Policy. Published July 7, 2016. https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2016/07/07/4-top-voting-issues-in-2016-election/

- Phillips, M. (2021). Trump says he will probably visit the southern border in coming weeks. New York Post, March 27, 2021. https://nypost.com/2021/03/27/trump-says-he-will-probably-visit-the-southern-border-in-coming-weeks/

- Pickard, V. (2018). Digital Journalism and Regulation: Ownership and Control. In Scott Eldridge and Bob Franklin (Eds.) The Routledge Handbook of Developments in Digital Journalism Studies, 211-222.

- Price, D. & Kaufhold, K. (2019). Bordering on Empathy: The Effect of Selective Exposure and Border Residency on Immigration Attitudes. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 63(3), 494-511. https://doi.org/10.1080/08838151.2019.1659089

- Radcliffe, D. & Ali, C. (2018, January 4). Local News in a Digital World: Small-Market Newspapers in the Digital Age. Tow Center for Digital Journalism. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3094783

- Reader, B. (2012). Community Journalism: A Concept of Connectedness. In Bill Reader & John A. Hatcher (Eds.) Foundations of Community Journalism. Sage.

- Reilly, K. (2016, August 31). Here Are All the Times Donald Trump Insulted Mexico.

- Time. Retrieved on June 25, 2018, from http://time.com/4473972/donald-trump-mexico-meeting-insult/

- Rizzo, S. (2018, June 19). The fact’s about Trump’s policy of separating families at the

- border. The Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/fact-checker/wp/2018/06/19/the-facts-about-trumps-policy-of-separating-families-at-the-border/

- Schweikart, L. (2014). Forward, in Jim A. Kuyper (Ed.) Partisan Journalism: A History of Media Bias in the United States. Rowman & Littlefield.

- Shafer, J. (2024. January 22). Old People Love Cable News – And They Vote. Politico. https://www.politico.com/news/magazine/2024/01/22/cable-news-decline-column-00136657

- Shearer, E. (2018). Social media outpaces print newspapers in the U.S. as a news source. Pew Research Center, December 10, 2018. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/12/10/social-media-outpaces-print-newspapers-in-the-u-s-as-a-news-source/

- Shepardson, D. (2019). U.S. court deals setback to FCC push to revamp media ownership rules. Reuters, September 23, 2019. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-media/u-s-court-deals-setback-to-fcc-push-to-revamp-media-ownership-rules-idUSKBN1W81YU

- Simpson, A. & Rios, K. (2019). Is science for atheists? Perceived threat to religious cultural authority explains U.S. Christians’ distrust in secularized science. Public Understanding of Science, 28(7), 740-758. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963662519871881

- Stroud, N.J. (2007). Media effects, selective exposure, and Fahrenheit 9/11. Political

- Communication, 24(4), 415-426. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584600701641565

- Tate, E. (2016, October 9). Another Newspaper Breaks Conservative Tradition With Endorsement Of Hillary Clinton. Huffington Post. https://www.huffpost.com/entry/columbus-dispatch-endorses-hillary-clinton_n_57ead04de4b082aad9b79b30

- TRAC Immigration (2024, April 21). ICE Detainees by Date and Arresting Authority. TRAC Immigration Data, Syracuse University. https://trac.syr.edu/immigration/detentionstats/pop_agen_table.html

- Vultee, F. (2023). Eid, Easter, and Christmas: Populist Outrage and the War on Professional Journalism. Journalism & Communication Monographs, 25(4), 375-379. https://doi.org/10.1177/15226379231201459

- Watson, B. & Riffe, D. (2012). Perceived threat, immigration policy support, and media

- coverage: Hostile media and presumed influence. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 25(4), 459-479. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijpor/eds032

- Wills, J. B. & Commins, M. M. (2018). Consequences of the American States’ Legislative Action on Immigration. Journal of International Migration and Integration, 19, 1137-1152. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12134-018-0588-7

- Yanich, D. (2016). Local TV News, Content, and the Bottom Line. Journal of Urban Affairs. 35(3). 327-342. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9906.2012.00637.x

About the Author

Kelly Kaufhold is an associate professor of digital media innovation in the School of Journalism and Mass Communication at Texas State University.

[pdf-embedder url=”https://tccjtsu.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/10-2-PDF.pdf” title=”10-2 PDF”]

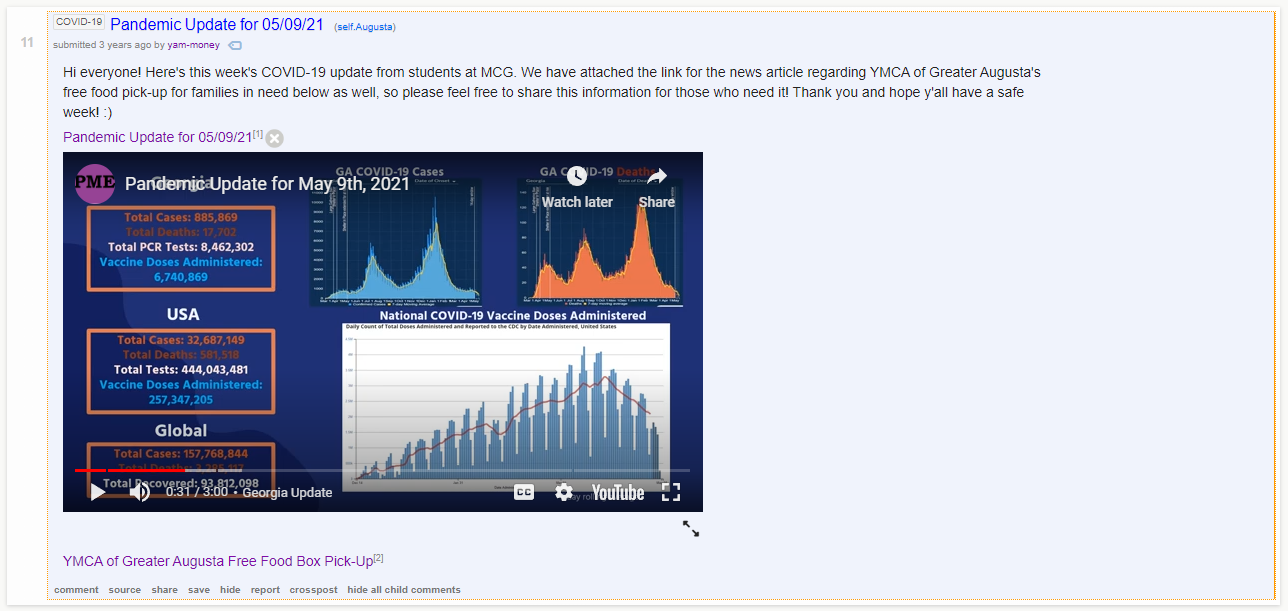

The next sub-group was 15 requests about vaccine information that broke down into various forms of specificity. Ten of the posts asked, generally, about the vaccine. Most of those general requests were questions about when others thought vaccines would be approved and when they would be available in their community. From there, seven were specifically requests about where vaccines were available in the early days of distribution. Earlier date requests tended to ask about large-scale drive-up and drive-through vaccination sites, and later dates tend to ask about which pharmacies had appointment availability. Two posts specifically asked about what the wait times were for mass-vaccination centers because they were trying to time their work lunch break correctly, and one-each was asking about where the 1-shot Johson & Johnson vaccine was available, asking if it was OK to skip the second dose of the two-shot vaccines, and asking which brand vaccine others planned on getting.

The next sub-group was 15 requests about vaccine information that broke down into various forms of specificity. Ten of the posts asked, generally, about the vaccine. Most of those general requests were questions about when others thought vaccines would be approved and when they would be available in their community. From there, seven were specifically requests about where vaccines were available in the early days of distribution. Earlier date requests tended to ask about large-scale drive-up and drive-through vaccination sites, and later dates tend to ask about which pharmacies had appointment availability. Two posts specifically asked about what the wait times were for mass-vaccination centers because they were trying to time their work lunch break correctly, and one-each was asking about where the 1-shot Johson & Johnson vaccine was available, asking if it was OK to skip the second dose of the two-shot vaccines, and asking which brand vaccine others planned on getting.