Abstract

Rarely has news deserts research examined a suburban region teeming with media outlets, and little attention has been paid to the neighborhoods of color within such an area. Through surveys and interviews with over three dozen community-based organization leaders and journalists, as well as a six-month, community-by-community audit of the coverage provided by 14 media outlets, this study aimed to determine whether one can reside in a news desert in densely populated Nassau County, NY, a suburb of New York City that is reported on by a wide range of large and small media outlets. In particular, we focused on the predominately Black and Brown neighborhoods therein. The majority of community-based organization leaders within these six areas contended the news media focused heavily or nearly exclusively on crime within their neighborhoods, and those perceptions were largely borne out in the quantitative data, except in the case of the two community newspapers, the Franklin Square-Elmont Herald and the Freeport Herald.

Introduction

The news deserts crisis caused by a decline in local reporting has been documented across the United States for more than a decade: a measurable deterioration in civic dialogue as a result of community and regional newspapers and other media outlets closing (Conte, 2022; Stites, 2018). The issue is exacerbated by a growing distrust of the mass media by a wide cross section of the population, particularly owing to the increasing polarization of the national news outlets (Garimella et al., 2021; Jurkowitz et al., 2020). The news desert, though seemingly a relatively new concept, has been a phenomenon in communities of color across the US since before the country was founded, often leaving them bereft of the essential information they need to make informed decisions and choices in this democratic society, even in regions with a multitude of robust media outlets (Conte, 2022; Gandy, 1997; González & Torres, 2011; Nelson, 1999).

One such region is Nassau County, NY, the nation’s 10th wealthiest county 33 miles due east of Midtown Manhattan, the center of the largest media market in the US, with 12% of the country’s newsroom employees (Baker, 2021; Grieco, 2019). This study will show that even in a suburban haven rich with a variety of news organizations, there exist news deserts spanning the majority of the six predominately Black and Brown communities that form what is known as Nassau’s “corridor of color”: Elmont (population 36,245, US Census Bureau, 2020), Freeport Village (44,199), Hempstead Village (58,734), Roosevelt (16,522), Uniondale (32,621), and Westbury Village (15,809).

If there are news deserts in largely Black and Brown neighborhoods in close proximity to what is often called the “media capital of the world,” New York City, then there are likely similar news information vacuums in communities of color across the US. Addressing whether suburban Black and Brown neighborhoods can be considered news deserts is crucial, in particular, because a majority of Americans—53%—live in suburbs, while 26% reside in cities and 21% in rural small towns (Kolko & Bucholtz, 2018). At the same time, suburbs are often misunderstood. They are widely seen as wealthy and majority-White, likely because they were historically so. Today, however, suburbs fully reflect America’s growing diversity. In 1990, approximately 20% of suburbanites were people of color. By 2000, that figure had risen to 30%. Today, it stands at 45% across the nation (Frey, 2022). In Nassau, people of color comprised 44.2% of the population as of June 1, 2022 (Census Bureau).

With a population today of approximately 1.39 million residents (Census Bureau, 2020), Nassau grew rapidly from a largely rural region, composed of small downtowns and farms, to crowded suburbia in the post-World War II era, with two cities, 64 incorporated villages, and 100 unincorporated areas that are divided among three towns—Hempstead, North Hempstead, and Oyster Bay (Nassau County website, Cities, Towns & Villages section). From the late 1940s through the ’60s, segregation was built into the economic model for development in this majority-White county, the specter of which lingers today.

Nassau is ranked the fourth most segregated county among 62 in New York State (Winslow, 2019), with segregation forming the basis for its development model dating back to a restrictive covenant preventing Black people and other underrepresented groups from moving into America’s first planned suburban community, Levittown, at its founding in 1947 (Lambert, 1997; Winslow, 2019). Levittown, which remains a majority-White community today (Census Bureau, 2020), may only be a 10- or 20-minute drive from the neighborhoods in this study, but racially and socio-economically, these areas have remained divided for decades (Winslow, 2019). Indeed, Nassau’s decades-long history of segregation looms large over Long Island, including, this study found, in the inordinate levels of crime reporting that the six studied communities received compared with other critical issues. In a six-month news audit that we conducted, we found issues-oriented coverage was limited or nearly absent, depending on the neighborhood.

The two notable exceptions were Elmont and Freeport, each with a working community newspaper that provided coverage across a wider range of issues for residents. Absent such hyperlocal outlets to offer counternarratives that provide context, news consumers may be led to believe neighborhoods of color such as these are trapped in a continuous cycle of violence, with few, if any, redeeming qualities, perpetuating a biased public perception of them while leaving them starved for vital issue-oriented and events-based reporting.

Grounded theory (Chun Tie et al., 2019; Glaser & Strauss, 1999) formed the basis for our research methodology in this study. We began by collecting qualitative data to assess how leaders in the six studied communities perceived the news media’s coverage of their neighborhoods through surveys and focus groups. Then, we sought data on the actual coverage that could be systematically collected, analyzed, and compared (Chun Tie et al., 2019; Glaser & Strauss, 1999) in order to ground the CBO leaders’ assertions and arguments in hard evidence. As well, we sought the thoughts and opinions of more than a dozen journalists. Through our study, we shall show how the news desert concept can be utilized to frame and understand media exclusivity in communities of color and the mainstream news media’s centuries-old stereotyping of Black and Brown people.

Literature Review

For this study, we took a community-by-community approach to studying the six news ecosystems outlined above. In our quantitative research in particular, we noted a clear difference in how mainstream regional news organizations and community media at the grassroots level approach coverage, with larger media centered, by and large, on crime, and the handful of community-based newspapers focused more on the everyday lives of residents.

Efforts to define community journalism date back at least to 1952, with publication of The Community Press in an Urban Setting, by sociologist Morris Janowitz (Janowitz, 1952; Robinson, 2014), who employed a number of the same research methods as this study, developing neighborhood profiles, interviewing residents and journalists, and analyzing the contents of publications. The community press, Janowitz hypothesized, maintains “local consensus through the emphasis on common values,” linking community leaders and readers through editors and reporters (Hatcher & Reader, 2012, p. 27; Janowitz, 1952). Or, as Conte (2022) wrote, in chronicling “the mundane, [hyperlocal media outlets] knit community together through the moments that otherwise might be overlooked” (pp. 17-18).

By contrast, national and larger regional news outlets many times must focus on the “big” stories owing to the size and scope of their coverage areas. As Conte (2022) wrote:

“Most often, [these stories] tend to be murders, other truly heinous crimes, and high-profile incidents such as house fires. None of these bigger outlets have enough journalists to cover the small stories and the minutia of daily life, even though those are the events that make up the substance of any community” (p. 65).

Defining the news desert

The Hussman School of Journalism and Media at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill defines a news desert as “a community, either rural or urban, with limited access to the sort of credible and comprehensive news and information that feeds democracy at the grassroots level” (Hussman School, n.d., para. 4). This definition does not include suburbs, though a report sponsored by the Hussman School, The Expanding News Desert, speaks of a growing “silence in the suburbs” caused by the closure of hundreds of suburban community weekly newspapers between 2004 and 2018 (Abernathy, 2018, p. 11).

To date, news deserts research has focused primarily on rural and urban communities that have lost their media outlets. Largely unanswered in the current literature is whether a suburban community with a wide range of media outlets to cover it could also be a news desert. This gap in the literature may be owing to a widely held belief that most suburbs are well-covered by news outlets because they primarily fall within the orbits of major metropolitan media markets with many outlets. As this study will show, a simple count of news organizations alone does not speak to the health of a local, or grassroots, media ecosystem, though. The coverage produced by news organizations must be examined through thematic, content, and textual analysis as well.

In March 2021, Impact Architects released a diagnostic framework to determine the health of local news and information ecosystems. The John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, the Democracy Fund, and the Google News Initiative funded the research behind this new framework (Stonebraker & Green-Barber, 2021). The authors conducted qualitative research through surveys, focus groups, and listening sessions with three key groups: community members, journalists, and representatives of other information providers such as community organizations, libraries, and universities. “The health of a news and information ecosystem can’t be understood by the presence or absence of journalism organizations alone,” the framework developers argued (Stonebraker & Green-Barber, 2021, p. 10).

Their report outlined six key factors in determining the vitality of a news and information ecosystem:

- Number of journalism organizations serving a community.

- Types of media.

- The news outlets’ business models.

- The diversity of media, including the number of BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and People of Color) news organizations.

- Collaboration among media companies.

- Nonprofit funding available to the outlets.

In our study of news and communications deserts in Nassau County, we considered each of the above six metrics, conducting surveys, focus groups, and listening sessions with community organization leaders and journalists. To determine the health of a news ecosystem, however, the nature and quality of newspaper articles and TV and radio broadcasts about a community must also be examined through quantitative research to determine whether people’s information needs have been fulfilled and satisfied—and whether the news information distributed to the public ultimately encourages or discourages civic discourse and engagement, and/or distorts reality. Thus, we carried out a thematic news audit within the six studied communities over six months in 2022, the results of which demonstrated that news coverage primarily or nearly exclusively centered on crime and education in four of the six areas, with little to no reporting on other critical issues. Thus, we are calling these neighborhoods news deserts.

The term news desert entered the mainstream journalistic lexicon a little over a decade ago, after thousands of print journalists had been laid off and hundreds of newspapers had shut down operations starting in the early 2000s, leaving a steadily decreasing number of communities without media outlets of their own (Abernathy, 2018; Conte, 2022). Due in large part to the digital news revolution, coupled with a societal move toward social media, the past two decades have seen a sharp decline in print circulation at daily and weekly newspapers and thus advertising dollars, forcing the layoffs of more than 40,000 journalists from 2004 to 2022 (Abernathy, 2018; Claussen, 2020; Robinson, 2014; Waldman, 2022). During that same period, the US lost 2,500 newspapers (Simonetti, 2022).

The news desert was not, however, a new concept in communities of color, which for centuries were ignored and stereotyped by mainstream media organizations (Gandy, 1997; González & Torres 2011; Nelson, 1999), including, this study found, in Nassau County today to a large extent. For more than 250 years, the nation’s news media, regardless of political leanings, had remained central institutions of White America, according to González and Torres (2011). Native American, African American, Hispanic/Latino, and Asian American journalists were “systematically excluded” from newsrooms across the country through the 1970s, the two wrote (2011, p. 8). The lack of representation in newsrooms resulted in an “almost routine distortion of the lives and events of people of color by the press,” they emphasized (p. 15). For the roughly 204,000 residents of the six neighborhoods included in this study, little has changed since the ’70s, it appears.

News media representations of Black and Brown people

Overt racism may have largely disappeared from today’s media portrayals of people of color in the mainstream press, but many news organizations often ignore them and their issues while remaining focused, by and large, on crime coverage in their neighborhoods; as a result, news media many times fail to address the Critical Information Needs (CINS) of Black and Brown people (Keene & Padilla, 2013; Nishikawa et al., 2009; Wenzel & Crittenden, 2021).

At the same time, the media’s focus on crime in Black and Brown communities, we found in this study, can cause a clustering effect, whereby several outlets cover the most shocking criminal activity in these areas all at once, potentially leading the public to believe these communities are experiencing more crime than they do. This effect was described nearly 30 years ago by Sacco (1995), who noted that variations in the volume of crime coverage appeared unrelated to the actual number of crimes taking place within a given area. Crime statistics indicated that most crime was nonviolent three decades ago, but aggregated news media reports suggested otherwise, according to Sacco.

Gandy (1997) noted that continual coverage of crime in communities of color can give the wider public the impression that people of color, particularly Black people, are dangerous by nature. Gandy argued that the media tended to present people in strictly negative terms. The cumulative result of such coverage may be to reduce public social programs designed to support underrepresented and marginalized populations, according to the author, potentially exacerbating feelings of isolation and alienation in communities of color that are news deserts.

In fact, it appears the term news desert was popularized, at least in part, because of the dearth of original, quality reporting in and on communities of color. In an April 5, 2011, column for These Times Magazine, The Paradox of Our Media Age—And What to Do About It, Chicago-based writer Laura Washington described what she called the “communications desert.” In urban areas, most news decision-makers remained White, wrote Washington (2011), noting, “Reporters parachute into black and Latino neighborhoods to cover violent crime and community conflict” (para. 18).

Washington’s column helped thrust the term news desert into the fore (Conte, 2022). Shortly after its publication, Washington appeared beside Tom Stites, a media fellow at Harvard University’s Berkman Klein Center for Internet and Society, at a conference at which Washington explained her concept. Stites then began pushing out the notion of the news desert, stating, “Elites and the affluent are awash in information designed to serve them, but everyday people, who often grapple with significantly different concerns, are hungry for credible information they need to make their best life and citizenship decisions” (Conte, 2022, p. 17).

The percentage of journalists of color in newsrooms has grown but remains well below the percentage of the population comprised by people of color. In 1982, journalists of color made up 3.9% of newsrooms; in 1992, 8.2%; and in 2013, 10.8% (Willnat et al., 2022). As of 2018, people of color comprised 40% of the US population, but 17% of American newsrooms (Arana, 2018). Four years later, the newsroom figure had inched up by one percentage point, to 18% (Willnat et al., 2022).

Johnston and Flamiano (2007) noted there was evidence, based on findings at four major daily newspapers, to suggest that a lack of newsroom diversity affects news coverage, with people of color underrepresented as sources for and subjects of stories. Since the early 2000s, at least some newspapers have apologized for how they covered Black communities in the past (Burke, 2022; Neason, 2021; Pinsky, 2023). In 2021, after the Black Lives Matter protests, The Kansas City Star, among a growing number of American dailies that have sought to atone, undertook an introspective examination of its past coverage. In the editorial The Truth in Black and White: An Apology from The KC Star, Martin Fannin, the outlet’s president and editor, remarked:

Reporters were frequently sickened by what they found — decades of coverage that depicted Black Kansas Citians as criminals living in a crime-laden world. They felt shame at what was missing: the achievements, aspirations and milestones of an entire population routinely overlooked, as if Black people were invisible (Fannin, 2020, para. 14).

Patterns of coverage in communities of color

Why journalists remain focused on crime within communities of color, even now in a post-George Floyd era, is an open question and a potential source of debate. Script theory, developed by psychologist Silvan Tomkins in the 1950s, may suggest at least a partial answer.

Conceptual scripts—set patterns of doing and of being within society that humans utilize daily—aid us in interpreting and defining our ever-changing world (Tomkins, 1987). A conceptual script can be thought of as a heuristic, or mental shortcut. The script comprises a set of familiar scenes, each of which begins with a stimulus (an event), which is followed by an affect (an outward expression of emotion that demonstrates motivation) and then a response, according to Tomkins.

Thomson (2016), who studied visual representations in the news, employed script theory to show how the photojournalists he was studying often relied on deeply entrenched scripts to frame their stories when packaging the news. Conceptual scripts enable journalists to produce stories quickly and efficiently on deadline, Thomson noted, but they can also lead journalists to fall back on historically scripted narratives about people of color, portraying them as collectively angry, for example, rather than seeking individual opinion from them and reporting nuance. The researcher further demonstrated that people of color are often overlooked or ignored by the news media.

Thomson called on photojournalists to engage on a deeper level with subjects to learn about them as people and present their stories fully. A number of Black protesters interviewed by Thomson following the mass protests for racial equality at the University of Missouri at Columbia in 2015 noted photojournalists had not sought their names during the rallies after photographing them, leaving them as nameless faces. Images of racial integration within the protests also were not shown. Media outlets “tend to exclude and marginalize” the positive traits of people of color while focusing on the negative, Thomson concluded (2016, p. 224).

As well, resource allocation appears to play a part in how and why majority-White communities are often better served by the media than are communities of color. A study on the Critical Information Needs of communities by (Napoli et al., 2016) in Newark, New Brunswick, and Morristown, New Jersey reported that Morristown, the wealthiest, least diverse of the areas, with a population of roughly 20,000, had 10 times the number of journalistic resources than did Newark, the lowest-income, most diverse area, with a population of more than 307,000 people (Napoli et al., 2016; Census Bureau, 2022). As a result, Morristown residents received 13 times more coverage than did their Newark counterparts (Napoli et al., 2016).

It is little wonder then that studies indicate news consumers of color, especially in lower-income areas, are less satisfied with media coverage than are residents of more affluent areas. Hamilton and Morgan (2018) argue, “Income inequality readily translates into information inequality in the United States . . . . Poor people get poor information, because income inequality generates information inequality” (p. 2832).

In short, implicit, deeply held biases that have remained embedded in mainstream journalists’ daily scripts for centuries, coupled with a lack of newsroom diversity and significantly fewer reporting resources dedicated to communities of color, often leave these areas as news deserts, or information vacuums that are filled by the easiest, simplest form of reporting—crime.

For this research project, we addressed these questions:

RQ1: How are the six largely Black and Brown communities at the center of Nassau County, NY, presented in news coverage?

RQ2: How do community leaders within these areas think and feel about news reporting on their neighborhoods and constituencies?

RQ3: Do the leaders’ perceptions of news coverage align with actual media reports?

RQ4: To what degree are the six communities excluded from the media, leaving them as potential news deserts, or information vacuums?

Methods

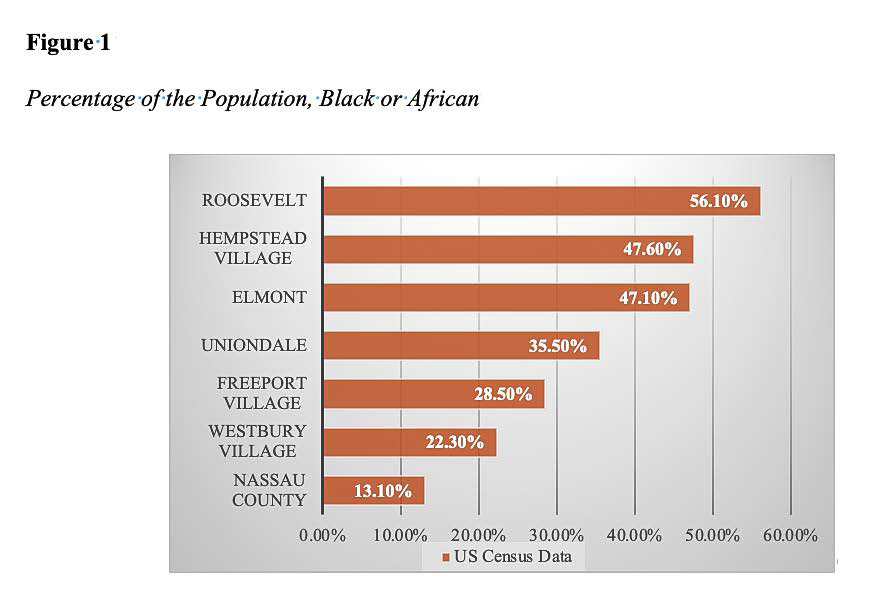

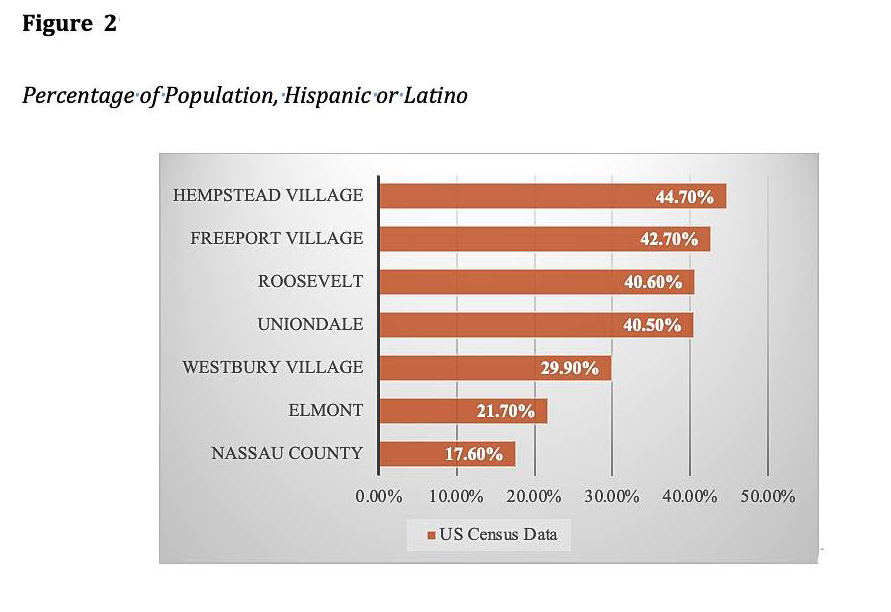

As shown in Table One here, each of the six studied communities falls below Nassau County’s US Census average for household income, which as of 2020 was $120,036. As shown in Figures Two and Three below, the populations of the six communities are largely Black and Hispanic.

Table 1

Average Household Income by Studied Community

| Community | Household Income |

| Hempstead Village | $62,569 |

| Freeport Village | $81,958 |

| Roosevelt | $90,423 |

| Westbury Village | $101,671 |

| Elmont | $104,671 |

| Uniondale | $105,307 |

Source: U.S. Census Bureau

Figure 1

Percentage of the Population, Black or African

Figure 2

Percentage of Population, Hispanic or Latino

In this three-phase, mixed-methods study, we first approached the question of whether critical local news information needs were being met through a qualitative lens, surveying and interviewing leaders of 21 community-based organizations (CBOs), along with a dozen editors and reporters. The study then layered on a quantitative review of the news information regarding each of the six studied communities. Data was analyzed sequentially, with results from the qualitative inquiry helping to inform the quantitative analysis. Lists of CBOs and news organizations were developed with the aid of library and newspaper directories and the annual Press Club of Long Island Media Guide. From there, key figures at the organizations were identified and invited by email and phone to take part in our research project.

Through triangulation of data—the surveys, interviews, and a news information audit—the health of each of the six media ecosystems could be gauged, and the influence of news organizations on a community, for better or for worse, could be assessed. Researcher triangulation was employed to help ensure the accuracy and validity of findings, with three researchers carrying out each of the study’s phases together.

To determine the level of access to news information, 18-questionsurveys were sent to the CBO leaders and 12-question surveys to the journalists in this study and recorded with Qualtrics software. The CBO surveys focused on how often groups had reached out to the media for—and whether they had received—coverage of their issues. The surveys of media organizations addressed the resources committed to covering the six communities and the frequency of reporting within them.

Interviews were then conducted during two focus group sessions, which were held in June 2022. The first, with the CBO leaders, took place at Hofstra University’s Lawrence Herbert School of Communication. Participants were divided into five tables, with leaders from two to five CBOs represented at each. Participants discussed two primary prompts, including, “What are some of the effective channels or methods that you and your organization have used to tell your community’s story?” and “How would you describe the way in which your organization or your constituents are represented in the media?” Groups developed consensus responses, which were presented to the larger gathering in a town-hall format. Research assistants recorded both the table discussions and the town-hall session, transcripts of which were later printed and analyzed.

The second session, with a dozen journalists, was conducted over Zoom. The reporters and editors responded to questions individually within the larger group. Two main prompts were discussed, including, “Talk a little about the origin of your stories” and “What are the challenges of connecting with sources at community-based organizations?” The Zoom session was recorded, and a transcript was printed and reviewed.

An audit of news stories, covering the period from January 1 to June 30, 2022, was then carried out, with work beginning in September 2022 and concluding four months later in December. The first objective was to identify and record all or nearly all the stories produced by 14 media outlets that were identified as providing coverage for the six communities, listed below in Table Two.

Table 2

Media Outlets in the News Audit

| • Anton Media Group (Nassau Illustrated and Westbury Times, both weekly newspapers) |

| • Herald Community Newspapers (Franklin Square-Elmont Herald and Freeport Herald, both weeklies) |

| • Newsday (the only Long Island-based daily newspaper) |

| • News 12 Long Island (TV) |

| • The Daily Mail |

| • The Daily News |

| • The Long Island Press (a news and lifestyle monthly publication) |

| • The New York Post (a daily newspaper) |

| • The New York Times (the largest of the daily newspapers in the study) |

| • WABC Eyewitness News (TV) |

| • WCBS New York (TV) |

| • WCBS NewsRadio 880 FM |

| • WNBC New York (TV) |

Fewer than 500 stories were culled from among several thousand possibilities in the NewsBank and Newsday Recent databases and through Advanced Google Boolean site searches of the news organizations themselves. Two research assistants were trained in Boolean searching of the databanks, and they helped to pull stories from them. Hard copies of the three local weekly papers—the Franklin Square-Elmont Herald, Freeport Herald and Westbury Times/Nassau Illustrated—were also examined, as they did not post all their stories online. The articles and/or broadcasts were each analyzed and coded according to issue or topic: crime, education, environment, government, politics, etc. They were also separated into one of two categories, depending on whether a piece was episodic, focusing on a particular story in one of the six communities, or whether it was thematic, including a community in a quote and/or caption as part of regional coverage on a larger issue or feature. All data points, including the media outlets in which the pieces appeared, the story headlines, and their publication and/or broadcast dates, were recorded in one of four Excel spreadsheets.

The Results section below begins with qualitative data from the CBO leaders and journalists, followed by quantitative data on the categories and number of stories that were reported in the six communities, with deeper examinations of their headlines and images.

Results

The community-based leaders’ perspective

In the surveys and interviews with more than two dozen leaders of the community-based organizations in this study, two key coverage themes emerged: one, news outlets were often unresponsive to their issues, and two, the media focused disproportionally on crime coverage. The leaders insisted there was a great deal more to their communities than the felonies and other sensational narratives that often define them in news coverage, but they said stories of hope and resilience were many times ignored by reporters, potentially leaving the impression in the minds of readers, viewers, and listeners that their neighborhoods were plagued by crime, particularly violent crime.

In a Qualtrics survey of 27 CBO leaders from the six studied communities, 17, or nearly 63%, said coverage of their neighborhoods and issues was “mostly peripheral and/or sensational,” while seven, or roughly 26%, said it was “very attuned to local needs.” Three said other. Among those who responded other, one said news media were “always multitasking,” while another described news outlets as “fickle, seldom interested in our population, our issues, or the evolution of services.” The third did not understand the question.

To the focus-group question of whether and how a CBO had sought coverage with a news organization within the past year, one leader responded that “negative and tragic stories are really what’s driving the headlines,” adding, “The grassroots news is really what’s kind of falling by the wayside.” By grassroots, this respondent was referring to community-based reporting.

To the focus-group question of how the CBO and its community were represented in the media, one respondent remarked, “All you ever hear about is crime and poverty and everything negative that [the media] can dig up about [these] neighborhoods.” As this study’s quantitative data will show, that was often the case in most of the six studied communities.

Another noted that coverage was generally positive at two points in the year—Thanksgiving and Christmas—“and then the rest of the year we’re sort of, you know, not on the top of everybody’s minds.”

One leader of a CBO that works with the formerly incarcerated described media misrepresentation as relentless, remarking, “When we’re talking about disinformation and misrepresentation in media, it’s something that we unfortunately encounter every day.”

Another CBO leader expressed concern for how media reports reflect on her group’s constituents, stating, “We’re trying to control how we’re perceived in the media, which involves, of course, prewriting these press releases . . . We don’t want to be misrepresented because the populations we serve, we don’t want them to be viewed negatively.”

The adjective most often used to describe the media’s coverage of the six communities and the CBOs themselves was “negative”—nine times during the focus-group interviews.

The journalists’ viewpoint

The 12 journalists in this study reported they were often frustrated by a lack of resources to cover the six studied communities and the neighborhoods beyond them. There were fewer editors and reporters at each of the outlets than there were in the past. Certain media organizations reduced staff members during the coronavirus pandemic and never brought them back. One outlet had recently merged three local weekly newspapers into one, with a single editor to cover the same territory that two or three once did.

To a survey question inquiring about the constraints that the journalists might face in reporting stories, one weekly editor said, “I have a feeling . . . I’ve disappointed many people. I get almost on a weekly basis calls, emails, texts, people asking, begging, pleading [with] me to look into something or other. I just don’t have the bandwidth.”

Another weekly editor noted, “I wish I could split myself like the sorcerer’s apprentice and send myself all over Hempstead.”

The experiences of these Long Island-based journalists reflect the national trends described in the Literature Review, with newsroom staff reductions spreading editors and reporters considerably thinner than they had been in the past, forcing many journalists to take what were considered “reporting shortcuts” a decade ago, emailing interview questions to sources (Loeppky, 2022), for example, rather than conducting street-level, in-person interviews, the traditionally recommended method of shoe-leather newsgathering. In a survey question of 14 journalists in this study regarding their preferred means of communicating with sources, 72% said either email or phone, while 14% chose face-to-face interviews, though in their focus-group interview, the journalists did report they were “boots on the ground” in the studied communities. One station executive noted that her organization had recently held a series of “community convenings” to hear about people’s issues.

Regardless, gaining trust within historically marginalized communities can be a challenge not only because of limited resources, but also because of widespread fear of media misrepresentation among local leaders and residents, the journalists reported. As one deputy editor stated, “You may go [into] Wyandanch or Hempstead, you want to talk to somebody, but they don’t want to talk to you, because they don’t think you’re going to present their side fairly.”

Crime stories

The news audit identified (N=469) stories on at least one of the six studied communities. Of those, 43.28%, or (n=203), were produced by the two Heralds; followed by Newsday, with 29.85% of stories, or (n=140); and then the 11 other media outlets, with almost 26.87%, or (n=126).

Herald Community Newspapers included the Franklin Square-Elmont Herald and the Freeport Herald. The aggregated news organizations comprised Anton Media Group, News 12 Long Island, The Daily Mail, The Daily News, The Long Island Press, The New York Post, The New York Times, WABC Eyewitness News, WCBS New York, WCBS NewsRadio 880 FM, and WNBC New York.

Statistically, crime pervaded coverage in a majority of outlets. Nowhere was this more evident than in Uniondale, an unincorporated area of the Town of Hempstead (population 793,526, Census Bureau, 2020) that had the highest percentage of crime stories in the news audit. In this community, 51% of the total news coverage—26 of 51 articles and broadcasts—was crime-related over the six months of the audit. When Newsday was removed from the mix of outlets examined, crime coverage rose to 73% of stories on Uniondale, or 19 of 26. Meanwhile, no critical issues other than education were covered in the community.

Much of the Uniondale coverage came from five sources—Newsday, News 12, The Daily Mail, WABC Eyewitness News, and WNBC New York—with only a handful of stories from other outlets. Table Three gives a breakdown of crime coverage in Uniondale versus other reporting for each of the five outlets.

Table 3

Crime Stories by Outlet in Uniondale

| Outlet | Crime and Police Stories In Uniondale |

Stories Other Than Crime |

Total Stories | Crime As a Percentage of Coverage |

| News 12 | 5 | 1 | 6 | 83% |

| Daily Mail | 4 | 1 | 5 | 80% |

| WABC | 3 | 1 | 4 | 75% |

| WNBC | 3 | 1 | 4 | 75% |

| Newsday | 7 | 18 | 25 | 28% |

In the five other communities within this study, crime as a percentage of coverage was as follows below. Reporting by Newsday, the two Heralds, and the Westbury Times/Nassau Illustrated newspaper was excluded from these figures.

- Hempstead Village: 62%

- Elmont: 60%

- Westbury Village: 36%

- Freeport Village: 25%

- Roosevelt: 25%

Across all six communities, an average of 25% of Newsday stories was crime-related, reaching a high of 46% in Hempstead.

Crime comprised a significantly lower percentage of the two Heralds’ coverage in Elmont and Freeport when compared with the above media outlets’ reporting. In the Franklin Square-Elmont Herald, crime accounted for 7.3% of the total coverage, and in the Freeport Herald, 3.28%.

In March 2022, The Westbury Times became Nassau Illustrated, which no longer covered Westbury full-time, but rather mostly aggregated stories from papers throughout the newly reconstituted eight-edition Anton Media Group. Five Westbury Times/Nassau Illustrated stories were on Westbury itself during the six-month audit. Meanwhile, there was one story on a murder in Uniondale, one on a fatal drunken-driving crash in Uniondale, and one on a murder in Hempstead, despite neither of the two communities falling within the coverage areas of Anton Media newspapers, which are based mainly in upper-income, majority-White neighborhoods on Nassau County’s North Shore, often referred to as Long Island’s “Gold Coast,” or middle-class, majority-White areas on Nassau’s South Shore (see AntonNews.com).

Overall, crime comprised nearly a quarter of all coverage in the 14 media outlets, at 23.2%, or 109 of 469 stories.

Issue-oriented stories

At the outset of this study, a list of 11 critical community issues, or themes, was developed against which media coverage could be evaluated to determine which of them had received substantive coverage within the six communities. Of 16 respondents, nearly half—7.3—said the media had provided either no coverage or poor coverage on the 11 issues, with immigration, youth empowerment, and gender receiving the lowest average marks. Table Five provides the respondents’ mean ratings for the issues, from highest to lowest.

Table 4

Community-based Leaders’ Ratings of News Coverage

| Issue | Mean Score |

| Culture/Arts | 1.8 |

| Food/Nutrition | 1.76 |

| Police Reform | 1.6 |

| Education | 1.56 |

| Healthcare | 1.56 |

| Housing | 1.38 |

| LGBTQ+ Issues | 1.27 |

| Environment | 1.13 |

| Gender | 1.07 |

| Youth Empowerment | 1.06 |

| Immigration | 0.88 |

Meanwhile, in a survey of 10 journalists who cover the six studied communities, education, the environment, and housing were reported to be the most frequently covered issues, and LGBTQ+ issues, police reform, and gender were the least.

Table 5

Journalists’ Reported Frequency of News Coverage

| Issue | Mean Score |

| Education | 4 |

| Environment | 3.44 |

| Housing | 3.44 |

| Healthcare | 3.38 |

| Culture/Arts | 3.20 |

| Immigration | 2.86 |

| Youth Empowerment | 2.63 |

| Food/Nutrition | 2.38 |

| LGBTQ+ Issues | 2.33 |

| Police Reform | 2.25 |

| Gender | 1.75 |

In the news audit, the one issue among the 11 to receive coverage of any significance was education—115 of 469 stories, or 24.5% of total reporting. However, 59% of these stories—or 68 of the total—appeared in the Franklin Square-Elmont and Freeport Heralds.

Table Seven below gives the total number of stories for each of the issues that appeared in the 14 outlets during the news audit. It should be pointed out that half of the culture and arts stories—15 of 30—were published or broadcast during one of two times—the week of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s birthday on January 15 and in February, Black History Month.

Table 6

Stories Covered by Issue

| Issue | Total Number of Stories | Percentage of Overall Coverage |

| Education | 115 of 469 | 24.5 |

| Culture/Arts | 30 | 6.4 |

| Healthcare | 16 | 3.4 |

| Housing | 9 | 1.9 |

| Environment | 7 | 1.5 |

| Youth Empowerment | 6 | 1.3 |

| Immigration | 2 | .42 |

| Police Reform | 2 | .42 |

| Food/Nutrition | 1 | .2 |

| LGBTQ+ Issues | 0 | 0 |

| Gender | 0 | 0 |

Fifty-six percent of Newsday’s coverage of the six communities (79 of 140 stories) was thematic, with one or more of the communities included in a quote, photo caption, and/or paragraph as part of regional coverage on a larger issue or feature, while 44% was episodic, focused on a single story in a particular neighborhood. Among the aggregated media, 12.7% was thematic (16 of 126 stories), while 87.3% was episodic. And among the two Heralds, 8.4% was thematic (17 of 203 stories), while 91.6% was episodic. It should be noted, though, that 99% of Freeport Herald stories were focused on the community, making it the most hyperlocal outlet in this study.

The many thematic stories found in Newsday’s coverage provided overviews of big-picture Long Island stories and thus did not hone in on the six studied communities with depth, while its episodic stories did, as did the overwhelming majority of the Heralds’ stories. A number of CBO leaders noted they were often called for a “quick” quote or statistic on a larger issue rather than a deeper report on their organizations and their constituencies. Meanwhile, the aggregated media’s stories were primarily episodic because many of them were breaking-news pieces that applied only to a specific community.

Headlines

The proclivity of news organizations to center crime, as seen most conspicuously in Uniondale, often caused the clustering effect described in the Literature Review, whereby a string of startling story headlines from competing outlets appeared in the news cycle within short timeframes. Below are two samplings of 2022 headlines on Uniondale:

- “Police arrest 5th person in alleged MS-13 teen killing in Uniondale,” News 12, January 18.

- “Long Island MS-13 murderer, 22, is charged over FOURTH killing of teen murdered in woods in 2016,” Daily Mail, January 20.

- “LI MS-13 gang member sentenced for involvement in 4 separate killings,” WCBS News Radio, January 25.

- “Second man charged in gang killing of LI teen,” Newsday, January 27.

- “Police: 32-year-old fatally shot in Uniondale,” News 12, June 3.

- “Man fatally shot on quiet Uniondale street, stunning neighbors,” WABC Eyewitness News, June 3.

- “35 years for LI gang murder: Bloods member admitted string of violent crimes,” Newsday, June 18.

Quotes and photos

After the US Supreme Court handed down a decision in June 2022 expanding the right to carry firearms outside the home across all 50 states, New York strengthened its background requirements to own and carry a handgun and enacted a measure prohibiting concealed-carry permit holders from taking their firearms into “sensitive” locations such as Times Square, schools, and bars (Office of Governor Hochul, 2022).

On May 23, 2022, in the lead-up to the Supreme Court’s decision, The New York Times published the story, “The Latest on the Supreme Court’s Ruling and the Senate’s Passage of a National Gun Safety Law” (Astor, 2022). This national story included a photo of an unidentified gun shop in Hempstead, which was not otherwise cited in the piece. The image showed 12 large guns hung on a wall, with an American flag in black and blue below them. The caption read, “Rifles on Thursday at a gun store in Hempstead, N.Y.”

On June 23, The Times published the story, “Hochul Pledges New Legislation After ‘Shocking’ Court Decision on Guns,” about the governor’s plan to call a special legislative session to enact the new laws (Bromwich et al., 2022). The story included a quote from a Uniondale gun shop owner, Andrew Chernoff, who supported the Supreme Court’s decision.

On June 24, The New York Post published a story, “Eric Adams Says Private NYC Businesses Can Restrict Guns” (Crane, 2022). A photo of an unidentified gun shop in Hempstead illustrated the story, even though the piece was on New York City, not Nassau County where Hempstead is located. The close-up image showed two sets of White men’s hands fingering a Combat Master handgun above a glass countertop, with more guns inside the cabinet below.

There was not, in fact, a gun shop in Hempstead, NY (Village of Hempstead) at the time of this study, though there was a firearms training academy in the community. There were six gun shops throughout the wider Town of Hempstead, five of which were in majority-White neighborhoods and the one in Uniondale.

Discussion

Regardless of why The New York Times and New York Post ran these Associated Press images of gun shops, the photographs may have left readers with the impression that the Village of Hempstead had a gun shop when it did not. Moreover, the use of the quote and photos may have given readers the sense that Hempstead and Uniondale, two largely Black and Brown communities located next to each other, are heavily armed. No predominately White communities were selected for the three stories, despite the presence of gun shops in nearby Albertson, Franklin Square, Hicksville, Levittown, Merrick, Mineola, New Hyde Park, Rockville Centre, and Wantagh. According to the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives, New York had 1,785 licensed firearms dealers and pawn brokers at the time that this study was conducted (Stebbins, 2022), any one of which could have been chosen for a quote or photo to illustrate the above stories, but they were not.

Publishing quotes from and photos of guns shops in Black and Brown communities (correctly identified or not), without the use of similar imagery in White neighborhoods, suggests a form of implicit bias in their selection and could fuel long-held stereotypes of these areas as armed and potentially dangerous, as if the issue of gun safety were confined to them. Seemingly arbitrary editorial choices such as the above, when made repeatedly, could leave residents in communities of color feeling ignored and stereotyped, particularly when their voices are not heard and their issues are not covered with consistency, which leads us back to our research questions.

RQ1: How are the six largely Black and Brown communities at the center of Nassau County, NY, presented in news coverage?

The majority of community-based organization leaders within these six areas contended the news media focused heavily or nearly exclusively on crime within their neighborhoods, and those perceptions were largely borne out in the quantitative data, except in the case of the two community newspapers, the Franklin Square-Elmont Herald and the Freeport Herald. Further, our study demonstrated that Black and Brown people were often excluded from regional news media coverage, with critical issues rarely covered, if at all, the one exception being education. Meanwhile, two community media outlets provided more balanced coverage, with a wider array of issues addressed and, more particularly, local events and human-interest stories covered.

RQ2: How do community leaders within these areas think and feel about news reporting on their neighborhoods and constituencies?

There was strong agreement in the CBO leaders’ perceptions of and thoughts on coverage of their communities and their constituencies, both in the qualitative and quantitative data. It was particularly striking to see the agreement within the quantitative data. News media, the leaders contended, were either stereotyping them and/or ignoring them. Meanwhile, the journalists spoke about a lack of resources to cover these communities properly and/or a sense within these areas that CBO leaders and average citizens were reluctant to speak with the news media because of fears of misrepresentation.

RQ3: Do the leaders’ perceptions of news coverage align with actual media reports?

Based on our quantitative review of news coverage, it appears the CBO leaders’ perceptions of reporting on the six studied communities were largely accurate and represent a strong understanding of their media ecosystems. The leaders believed the news media centered crime in their areas, and that was to a great extent accurate, the two exceptions being the Franklin Square-Elmont and Freeport Heralds. We should note here, though, that even within the two communities with hyperlocal outlets, the overall percentage of crime coverage remained high at 60% in Elmont and 25% in Freeport. This was despite the relatively low percentage of crime reporting within the two Heralds.

RQ4: To what degree are the six communities excluded from the media, leaving them as potential news deserts, or information vacuums?

Regional media, particularly the broadcast outlets, often excluded the Black and Brown communities within this study from coverage other than crime reporting during the six months of our research. Newsday made a clear attempt to report stories other than crime but was often limited in such coverage to education. Moreover, a majority of its reporting was thematic, only including one of the six communities in a photo caption, quote, or paragraph instead of a full-fledged story. As well, one in four of its stories was crime related. Meanwhile, as noted, the two community news outlets within the study, the Franklin Square-Elmont and Freeport Heralds, covered a broader range of issues and events. Therefore, we conclude, at minimum four of the six communities—Hempstead, Uniondale, Roosevelt, and Westbury—could be considered suburban news deserts.

The community journalism model in crisis

The Franklin Square-Elmont and Freeport Heralds followed a community journalism philosophy and model, according to interviews with journalists from these publications. Crime made up a significantly lower percentage of overall coverage within the Franklin Square-Elmont and Freeport Heralds because these publications covered their assigned communities with regular, neighborhood-based reporting, thus addressing people’s Critical Information Needs, or at least working to do so, and providing context to the crime stories that were published. No community should be defined solely or primarily by the felonies and misdemeanors that occur within it. These newspapers followed that principle. Elmont and Freeport thus could be described as news oases by comparison to the four nearby deserts, despite the relatively high percentages of crime reporting on these two areas found in other outlets. Or perhaps it might be said community papers follow a different script (Tomkins, 1987) than that of larger regional news organizations, one less centered on that which might go wrong within a neighborhood and one more focused on that which goes right.

In today’s media landscape, however, smaller community outlets are fighting for survival in an increasingly competitive news ecosystem in which ever more people consume stories on social media, with less focus on their immediate neighborhoods (Vorhaus, 2020). At the same time, local media, once thought to be immune to the type of skeptical questioning by the public that national and regional outlets have long faced, are increasingly vulnerable to the same deficits in people’s trust as seen with larger media (Sands, 2019). And Robinson (2014) points out that communities, once defined by location, have become porous in digital spaces. Many people no longer define themselves first and foremost by where they were born and where they live, though these remain important elements of community identity, but they also associate themselves with shared ethnic, professional, or ideological groups, as well as common causes (Hatcher & Reader, 2012). Though people might be closely connected to their local neighborhoods, they are becoming more tied to global online networks that pull them outside their geographic boundaries. Already-small community publications, therefore, may only become smaller—and fewer in number—in the future. The US now loses two newspapers per week, most of them local outlets (Fischer, 2022; Karter, 2022).

As shown in this study, though, community-based media organizations, where they exist, serve as key information providers for communities of color that have traditionally been portrayed in mainstream media as crime plagued and poverty stricken. Community newspapers and TV and radio stations often provide context by showing residents for who they are, many times with a focus on the good.

Conclusion

To understand and properly report on Black and Brown neighborhoods, journalists need the support and time to be on the ground in these places—not in their offices or homes communicating with the public via email and phone. As Babz Rawls Ivy, editor-in-chief of the Black-owned newspaper Inner-City News, in New Haven, Connecticut, told the Poynter Institute for a February 2023 article:

“I’m in community. [Residents] know me, and they trust us because I’m in community, because I go to their events . . . Don’t show up just for the tragedy. Don’t show up just for the shootings and the trauma. Show up for the celebratory things” (Chan, 2023, The Power of Being Present, para(s). 2 & 5).

Here, we must acknowledge the indelible mark that Black-owned and -operated newspapers, often referred to as the “Black press,” have made in not only covering and giving voice to communities of color dating back to America’s first Black-owned and -operated newspaper—Freedom’s Journal, founded in 1827—but also in shaping American history and democracy (Nelson, 1999). The Black press, which has practiced community journalism since its inception, was instrumental in providing for the Critical Information Needs of the formerly enslaved in the years and decades of the Reconstruction Era following the Civil War (1865-77), in bringing about the Great Migration of southern Black people to northern cities in the early part of the 20th century, and in igniting the Civil Rights Era of the 1950s and 1960s (Nelson, 1999). However, the Black press, like most all community press, has steadily declined in influence since the 1960s and ’70s (Nelson, 1999), leaving many communities stereotyped and starved for information.

News media funders such as the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, the Democracy Fund, and the Google News Initiative would do well to focus their efforts to sustain journalism on supporting and expanding community outlets, the base of the US media ecosystem, in particular the Black press and other “ethnic media,” including the Hispanic press, the Native American press, the Asian press, and others. Within community-based news media, audiences find a counterbalance, a counternarrative, to provide context to the sensationalized crime coverage that too often defines communities of color. The essential mission of such hyperlocal media is to show communities in their true form, beyond the tragedies that often frame Black and Brown neighborhoods in larger news outlets.

Study limitations

Our study did not include majority-White communities for comparison to determine how they might be treated by the media, which was a limitation. In recent years, a number of news organizations have reported extensively on the many forms of systemic racism within American society. If this project could determine definitively that majority-White communities received preferential treatment in the news, without the heavy focus on crime coverage and with their critical issues covered, then it could indicate potential bias, possibly even a form of structural racism, within the media on Long Island and perhaps beyond. As well, it should be noted that a new newspaper, the Uniondale Herald, was opened on May 18, 2023, after this study was completed; therefore, it was not included in our findings.

Next steps

The next step in this project would be to conduct a similar mixed-methods study of surrounding majority-White communities, as well as to extend the study of Black and Brown areas to neighboring Suffolk County to gauge the repeatability of this project’s findings. From there, it would be a matter of continuing to expand the number of sampled communities, examining other regions of the country.

References

- Abernathy, P.M. (2018). The expanding news desert. University of North Carolina, Hussman School of Journalism and Media.

chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://www.cislm.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/The-Expanding-News-Desert-10_14-Web.pdf - The website of the Anton Media Group (n.d.), antonnews.com.

- Arana, G. (2018, November 5). Decades of failure: 17% of US newsroom staff is not white. Columbia Journalism Review. https://www.cjr.org/special_report/race-ethnicity-newsrooms-data.php

- Astor, M. (2022, June 23). The latest on the Supreme Court’s ruling and the Senate’s passage of a national gun safety law. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/live/2022/06/23/us/gun-control-senate-supreme-court

- Baker, K. (2021, April 6) Ranking the U.S.’ largest media markets. Axios. https://www.axios.com/2021/04/26/media-markets-ranking-largest-us

- Bromwich, J.E., Southall, A., & Ashford, G. (2022, June 23). Hochul pledges new legislation after ‘shocking’ court decision on guns. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/06/23/nyregion/hochul-new-york-gun-law-supreme-court.html

- Burke, L.V. (2022, March 12). White newspapers apologize for shameful past coverage of Blacks. Minnesota Spokesman-Recorder. https://spokesman-recorder.com/2022/03/08/white-newspapers-apologize-for-shameful-past-coverage-of-blacks/

- Chan, K. (2023, February 28). Journalists must understand the power of community engagement to earn trust. Residents of neighborhoods that have been misrepresented have lost faith that coverage will ever improve. Poynter Institute. https://www.poynter.org/ethics-trust/2023/why-trust-in-journalism-is-so-low-and-how-to-fix-it/

- Chun Tie, Y., Birks, M., Francis, K. (2019, January 2) Grounded theory research: a design framework for novice researchers, 7. SAGE Open Med, National Library of Medicine at the National Center for Biotechnology Information.

https://doi.org/10.1177/2050312118822927 - Claussen, D.S. (2020, October 4). Digesting the report: News deserts and ghost newspapers, Will local news survive? Newspaper Research Journal, 41(3), 255-259. Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication, Newspaper & Online News Division. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739532920952195

- Conte, A. (2022). Death of The Daily News: How citizen gatekeepers can save local journalism. University of Pittsburgh Press.

- Crane, E. (2022, June 24). Eric Adams says private NYC businesses can restrict guns. New York Post. https://nypost.com/2022/06/24/eric-adams-says-private-nyc-businesses-can-restrict-guns/

- Fannin, M. (2020, March 2) The truth in Black and white: An apology from The Kansas City Star. Today we are telling the story of a powerful local business that has done wrong. Kansas City Star. https://www.kansascity.com/news/local/article247928045.html

- Fischer, S. (2022, July 4) The local news crisis is deepening America’s divides. Axios. https://www.axios.com/2022/07/04/local-newspapers-news-deserts

- Frey, W. (2022, June 15). Report: Today’s suburbs are symbolic of America’s rising diversity: A 2020 census portrait. Brookings Institute.

- https://www.brookings.edu/articles/todays-suburbs-are-symbolic-of-americas-rising-diversity-a-2020-census-portrait/#:~:text=While%20there%20is%20still%20a,2000%20and%2045%25%20in%202020.

- Gandy, O.H. (1997). From bad to worse — the media’s framing of race and risk. In Dennis, E.E., & Pease, E.C. (Eds.) The media in black and white (pp. 37-44). Transaction Publishers.

- Garimella, K., Smith, T., Weiss, R., West, R. (2021, June 7-10) Political polarization in online news consumption [Paper presentation]. Proceedings of the 15th International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media, held virtually. https://doi.org/10.1609/icwsm.v15i1.18049

- Glaser, B., Strauss, A. (1999) The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Routledge.

- González, J., and Torres, J. (2011). News for all the people: The epic story of race and the American media. Verso.

- Grieco, E. (2019, October 24). One-in-five U.S. newsroom employees live in New York, Los Angeles or D.C. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2019/10/24/one-in-five-u-s-newsroom-employees-live-in-new-york-los-angeles-or-d-c/

- Hamilton, J.T., Morgan, F. (2018). Poor information: How economics affects the information lives of low-income individuals. International Journal of Communication, 12, 2832-2850. Annenberg Center for Communication, University of Southern California. https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/8340

- In J.A. Hatcher & B. Reader (Eds., 2012). Foundations of community journalism. Sage Publications Inc.

- Office of Gov. Kathy Hochul (June 2022). Governor announces new concealed carry laws passed in response to reckless Supreme Court decision take effect Sept. 1, 2022. https://www.governor.ny.gov/news/governor-hochul-announces-new-concealed-carry-laws-passed-response-reckless-supreme-court

- The website of the Hussman School of Journalism and Media, Center for Innovation and Sustainability in Local Media at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (n.d.) What exactly is a news desert? https://www.cislm.org/what-exactly-is-a-news-desert/

- Janowitz, M. (1952). The community press in an urban setting. The Free Press.

- Johnston, A., Flamiano, D. (2007, April 27) Diversity in mainstream newspapers from the standpoint of journalists of color. Howard Journal of Communications, 18(2), 111-131. https://doi.org/10.1080/10646170701309999

- Johnson, S.R. (2022, December 23). The 15 richest counties in the U.S. U.S. News & World Report. https://www.usnews.com/news/healthiest-communities/slideshows/richest-counties-in-america

- Jurkowitz, M., Mitchell, A., Shearer, E., & Walker, M. (2020, January 24). U.S. media polarization and the 2020 Election: A nation divided. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/journalism/2020/01/24/u-s-media-polarization-and-the-2020-election-a-nation-divided/

- Karter, E. (2022, June 29). As newspapers close, struggling communities are hit hardest by the decline in journalism. Northwestern Now. https://news.northwestern.edu/stories/2022/06/newspapers-close-decline-in-local-journalism/

- Keene, D.E., Padilla, M.B. (2013, July 25) Spatial stigma and health inequality. Critical Public Health, 24(4), 392-404. https://doi.org/10.1080/09581596.2013.873532

- Kolko, J., Bucholtz, S. (2018, November 14). America really is a nation of suburbs. Bloomberg.

- https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2018-11-14/u-s-is-majority-suburban-but-doesn-t-define-suburb

- Lambert, B. (1997, December 28). At 50, Levittown contends with its legacy of bias. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/1997/12/28/nyregion/at-50-levittown-contends-with-its-legacy-of-bias.html

- Loeppky, J. (2022, June 21). When email interviews, once considered ‘a last resort,’ are invaluable for reporters. Poynter Institute. https://www.poynter.org/reporting-editing/2022/email-interviews-journalism-good-or-bad/

- Napoli, P., Stonbely, S., McCollough, K., Renninger, B. (2016, February 23). Local journalism and the information needs of local communities: Toward a scalable assessment approach. Journalism Practice, 11(4), 373-395. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2016.1146625

- The website of Nassau County, NY, government (2023). Cities, Towns & Villages. https://www.nassaucountyny.gov/

- Neason, A. (2021, January 28). On atonement: News outlets have apologized for past racism. That should only be the start. Columbia Journalism Review. https://www.cjr.org/special_report/apologies-news-racism-atonement.php

- Nelson, S. (Director). (1999) The Black press: Soldiers without swords [Documentary film]. PBS. https://www.pbs.org/blackpress/

- Nishikawa, K.A., Towner, T.L., Clawson, R.A. Waltenburg, E.N. (2009, August 4) Interviewing the interviewers: Journalistic norms and racial diversity in the newsroom. Howard Journal of Communications, 20(3), 242-259. https://doi.org/10.1080/10646170903070175

- Pinsky, M.I. (2023, March 13). Maligned in black and white: Newspapers played a major role in racial violence. Do they owe their communities an apology? Poynter Institute. https://www.poynter.org/maligned-in-black-white/

- Robinson, S. (2014, November 29). Community journalism midst media revolution. Journalism Practice, 8(2), 113-120. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2013.859822

- Sacco, V. (1995, May). Media constructions of crime. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 539(1), 141-154.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716295539001011 - Sands, J. (2019, October 29). Local news is more trusted than national news — but that could change. Knight Foundation. https://knightfoundation.org/articles/local-news-is-more-trusted-than-national-news-but-that-could-change/

- Simonetti, Isabella (2022, June 29). Over 360 newspapers have closed since just before the start of the pandemic. The same pace — about two closures per week — was occurring before the pandemic. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/06/29/business/media/local-newspapers-pandemic.html

- Stebbins, S. (2022, June 28). This is how many gun stores there are in New York: In the United States, guns are big business. Patch. https://patch.com/new-york/across-ny/how-many-gun-stores-there-are-new-york

- Stites, T. (2018, October 15). About 1,300 U.S. communities have totally lost news coverage, UNC news desert study finds. Poynter Institute. https://www.poynter.org/business-work/2018/about-1300-u-s-communities-have-totally-lost-news-coverage-unc-news-desert-study-finds/

- Stonebraker, H., Green-Barber, L. (2021, March). Healthy local news and information ecosystems: A diagnostic framework. Impact Architects. http://files.theimpactarchitects.com/ecosystems/full_report.pdf

- Thomson, T.J. (2016, October-December). Black, white, and a whole lot of gray: How White photojournalists covered race during the 2015 protests at Mizzou. Visual Communication Quarterly, 23(4), 23-233. https://doi.org/10.1080/15551393.2016.1230473

- Tomkins, S.S. (1987) Script theory. In J. Aronoff, A. I. Rabin, & R. A. Zucker (Eds.) The emergence of personality (pp. 147–216). Springer Publishing Company.

- US Census Bureau data (2020) at https://census.gov.

- US Census Bureau data (2022) at https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/nassaucountynewyork/PST045222

- Vorhaus, M. (2020, June 24). People increasingly turn to social media for news. Forbes.

https://www.forbes.com/sites/mikevorhaus/2020/06/24/people-increasingly-turn-to-social-media-for-news/?sh=4ed576a53bcc - Waldman, S. (2022, February 25). Our local-news situation is even worse than we think. Columbia Journalism Review. https://www.cjr.org/local_news/local_reporters_decline_coverage_density.php

- Washington, L.S. (2011, April 5). The paradox of our media age—and what to do about it. In These Times. https://inthesetimes.com/article/the-paradox-of-our-media-ageand-what-to-do-about-it

- Wenzel, A.D., Crittenden, L. (2021) Reimaging local journalism: A community-centered intervention. Journalism Studies, 22(15), 2023-2041. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2021.1942148

- Winslow, O. (2019, November 17) Long Island Divided, Part 10: Dividing lines, visible and invisible. Newsday. https://projects.newsday.com/long-island/segregation-real-estate-history/

- Willnat, L., Weaver, D.H., & Wihoit, C. (2022). The American journalist under Attack: Media, trust & democracy. S.I. Newhouse School of Public Communications, Syracuse University. https://www.theamericanjournalist.org

About the Authors

Scott A. Brinton is an assistant professor of journalism, media studies and public relations at Hofstra University’s Lawrence Herbert School of Communication. He received his MA from Columbia University, Teachers College, and he is an MA candidate, at the University of Missouri School of Journalism at Columbia

Aashish Kumar is a professor of television and immersive media at Hofstra University’s Lawrence Herbert School of Communication. He received his MFA from Brooklyn College and has an MS from Indiana State and an MA Delhi University.

Mario A. Murillo is the vice dean and professor of radio journalism, media studies and Latin American studies at Hofstra University’s Lawrence Herbert School of Communication. He received his MA from New York University.

Conflict of interest statement

The study’s lead author, Scott Brinton, was formerly executive editor of Herald Community Newspapers, parent company of the Franklin Square-Elmont and Freeport Heralds. He was no longer employed by the Herald at the time of this study, and he did not have, nor does he have now, any financial or other interest in his former company. Rather, he was, and is now, a full-time Hofstra University journalism professor. Otherwise, there were no other potential conflicts of interest.